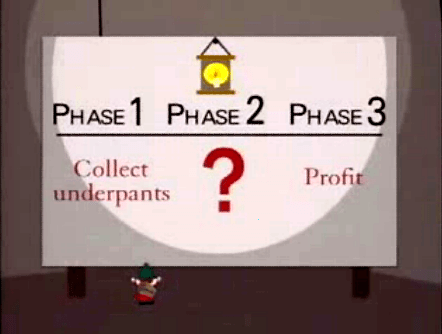

(image courtesy Southpark)

In 1998 Southpark presciently lampooned the entire Dot Bomb bubble in an episode called The Gnomes. Essentially the Gnomes had a business plan:

Step One: Collect Underpants.

Step Two: ?

Step Three: Profit.

The excellent Seeking Alpha writer Stephen Faulkner last year pointed out the similarities between Pandora’s business strategy and the Underpants Gnome’s business model.

However Pandora did eventually come up with a step 2. It’s called the Internet Radio Fairness Act. Basically this bill would ask the government to step in and mandate lower royalties to artists. Essentially a bill that would largely benefit ONE publicly traded company: Pandora (although curiously Pandora terrestrial radio competitor Clear Channel is signed onto the bill along with Google, what’s that about?, Here is a wild guess. Pandora is for sale.)

So basically this is the Pandora Underpants Business Model:

Step 1 Collect Users

Step 2 Ask Congress to pass a bill that benefits a single private company , by mandating lower royalties to artists for Pandora. Or perhaps more accurately Artists are forced by government to subsidize Pandoras bad business model.

Step 3 Profit. ( Stockholders cash out in sale to Clear Channel or Google?).

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

But here’s the thing. The so called Internet Radio Fairness Act was shot down in Congress, largely due to grassroots efforts by artists. But the rumour is the bill is coming back. And I’m gonna make a fairly educated guess as to what changes are gonna be in the bill.

While at a social event in Washington DC a rather transparent aparatchik of the telecommunications industry suggested a couple changes to the bill that might possibly meet the approval of the artists. Essentially it was this:

Why not lower Pandora’s royalties but give a larger percentage to the artists and less to the record labels.

Okay, so yeah I fucking fell off the turnip truck yesterday and that sounds like a really good deal! Sign me up!!

1). If IRFA passed, royalties from Pandora could be cut 85%. Even if artists got 100% of the royalties and record labels got zero we’d still take a whopping paycut of 70%.

2) Like most artists nowadays I own my own “masters” . That is, essentially I am the record company. Most independent artists are their own record labels. Therefore for the vast majority of artists this is exactly the same paycut and amounts to the Internet Radio Fairness Coalition saying “Artists are stupid and they’ll never catch on”.

(Ladies/Guys: after surviving in the music business for 30 years it should be a assumed that I have a finely tuned bullshit detector.)

So I’m gonna take a wild guess here:

The Internet Radio Fairness Act comes back next month with exactly this change. They think they are gonna be able to divide us from record labels. Not realizing that most artists are the record labels. A divide and conquer strategy. Let’s hope I’m not right. But just in case. Be ready.

David…This Underpants thing is a little too close for comfort-

Love- MYSTR Treefrog and The Smoking Gnomes.

http://www.thesmokinggnomes.com

What I find amusing is that, for all of the talk about artists and record labels needing to “explore new business models” or “adjust how they make money”, there’s never any such pressure on tech companies.

Companies like Pandora, even as they lose money hand over fist, are never pressured to adapt. Rather it has to be the fault of the greedy artists or record label.

Granted, I’m painting with a broad brush here and oversimplifying some arguments, but where is the call for Pandora to “explore new business models” for its service.

No one forced Pandora to accept the royalties it did. If they thought the rates were a bum deal, they could have walked. They looked at the rates, made their calculations and pulled the trigger. If they were wrong, they deserve to pay the price, not artists (much less competitors that might be able to do better).

I love Pandora as a service, it’s a neat product, but having a neat product does not entitle you to earn a living off of it (that argument is familiar from somewhere…).

Agree with you completely, Jonathan, and would even venture to elaborate further:

For some reason that remains unclear to me, tech companies seem to believe that they’re entitled to provide all content that has ever been produced or will be produced. What’s more, few other people seem to find there’s anything fundamentally wrong with the idea – Emily White’s “vast Spotify-like catalogue” is a consumer’s take. Lawmakers too seem to completely miss that such a one-stop-shop for everything is not only quite unlike any kind of offline business, but also a very dangerous thing to have.

A “shop” that stocks everything is going to have a very hard time doing business at a profit, for a start. “Everything” implies – rather strongly – that the majority of your stock isn’t going to be made (or owned) by you. That means you have to pay for it. Paying for everything a customer could possibly want is a vast undertaking, even if you can get a good mark-up on the downstream price – all the more so, if you want to have it all now (in advance of sales), in order to attract customers. The American approach to royalties means that you’ll eventually have to do a Pandora – digital royalties are already low, but once you multiply them by all that turnover, they’ll add up like crazy. Unless you’re making a profit on every “sale” (which happens seldom on the internet), you’ll soon see that even “fraction-of-penny” amounts threaten to nickel-and-dime you into bankrupcy. The European approach, as exemplified by Spotify, might mean that you do keep some portion off the top, but it’ll necessarily be a minority share – you can’t convince people to license your service otherwise, given that the effective royalties are miniscule. Spotify is racing against time now, trying desperately to build up sufficient scale to keep itself sustainable, before its licensors start jumping ship en masse. Even if it can reach profitability, there’s no guarantee that it can continue to provide a catalogue up to its users’ expectations, because it does not have the fallback of a compulsory license.

What’s more insidious about a one-stop-shop like this – and something that should certainly give lawmakers pause – is that it stands to become both a monopolist and a monopsonist. Essentially, it might become the gatekeeper that all things must pass through. Amazon is certainly trying to do that with publishing. Such an intermediary would have power hitherto unseen in its market.

While it’s understandable that such a future is any company’s wet dream, the fact that as a society we’re not only permitting it but actually encouraging it is something I find scary. You’d think we’d learned something from the financial crisis, at the very least.