HEARING BEFORE THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY

Select Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet

June 27, 2023

Testimony of Abby North

SUMMARY STATEMENT

Mr. Chairman, Members of the Subcommittee:

My name is Abby North. I am an independent music publisher and publishing administrator. I am a songwriter advocate. I am a technologist. I am a small business owner.

I began my career writing music, engineering and mixing recordings and ultimately created a

production music library. The library introduced me to music publishing.

My husband’s father was a film composer and songwriter named Alex North. When our family

had a worldwide reversion of rights in Alex’s song “Unchained Melody,” I wanted to learn about

global music publishing. “Unchained Melody” is a “standard” that has been recorded by thousands of artists but is best known as a recording by The Righteous Brothers in 1965. It is an “American Songbook” composition: one of the great songs of the 20th Century. Together, my family and the family of “Unchained Melody” lyricist Hy Zaret formed Unchained Melody Publishing LLC in 2013, and I began to administer our jointly owned copyright.

Unchained Melody Publishing then joined various foreign collective management organizations

(CMOs) and in doing so, I was able to identify incorrect or missing work and party metadata. By

correcting that metadata, I significantly increased our royalty collections. This is partly because

once I corrected our CMO registrations, our metadata stayed corrected over time.

Soon, other legacy songwriters and their families asked if I would administer their works as well.

As a music publishing administrator, I am responsible for accurately and comprehensively

maintaining metadata related to the musical works owned and created by my songwriter and

composer clients, their families and heirs. I must accurately and comprehensively register their

works with collective management organizations around the world.

These global CMOs rely on their music publisher affiliates to deliver works registrations that

clearly identify information about the musical works, about the songwriters and their publishing

entities, about the shares of the works that we own and collect, and about sound recordings that embody these songwriter’s works.

If we publishers do not register our works, we do not get paid and neither do our songwriters. It’s a simple equation: accurate, comprehensive metadata equals accurate, comprehensive royalty distribution.

THE MUSIC MODERNIZATION ACT

When I first heard about the Music Modernization Act and the possibility of a mechanical blanket license administered by one central CMO, I was pleased and hopeful. The previous method of one-off mechanical licensing was inefficient, unscalable, and absolutely

not meant for the digital distribution of music and the limitless supply of sound recordings being delivered to the Digital Service Providers. Blanket licenses can create efficiencies if based on authoritative and complete metadata.

In fact, every other CMO I am aware of outside of the United States has been blanket licens

mechanical rights for years. How exciting to see the United States catch up to the rest of the world’s CMOs!

That the Music Modernization Act was wholeheartedly supported by every sector of the music

business: songwriters, publishers, labels, artists and producers seemed like a modern-day miracle. We all have competing interests, but we came together, and the Music Modernization Act passed. I believed (and was promised) that the intention of the MMA was for a new authoritative database to be engineered and created, with closely interrogated and vetted, accurate, authoritative, comprehensive musical work, songwriter, publisher, performer and even sound recording data.

The music industry was told that The MLC’s data set was going to be the gold star standard that every global CMO could access and rely on.

Songwriters need this, and that’s what we were promised.

And, we were promised that the DSPs would pay for The MLC to perform this fundamental

obligation.

THE MECHANICAL LICENSING COLLECTIVE

The MLC Inc. won the assignment to be the first Mechanical Licensing Collective as created by

the MMA. We were told that after interviewing many competitors, The MLC, Inc. opted to engage the Harry Fox Agency as its data and back-end operations and administration vendor for an “unprecedented and truly revolutionary project.”

HFA has been integral to the music business since 1927. But the industry is well-aware that like

every other collective, HFA’s data is incomplete and sometimes inaccurate. Incomplete accounting by HFA was one driver of the push for the MLC in the first place.

One data set is not enough for the Herculean task of creating the best-in-class musical works

database. Based on my experience as a publishing administrator and technologist, I think that The MLC must license data from many providers, including HFA, Music Reports, SX Works/CMRRA, Xperi, and others.

Thus far, to my knowledge, the promised newly-created MLC database and new data set do not

exist.

When The MLC launched, it used slogans like “Play Your Part” to drive music publishers and

self-administered songwriters to sign up with The MLC, register their works and confirm the

completeness of The MLC’s data, often manually and on a song-by-song basis. But, it seems that “Playing Our Part” means doing The MLC’s job and devoting our own resources to the tasks the DSPs pay The MLC to do. Publishers have to go to The MLC to search for their works, one-by-one to see if the data and shares are correct. Publishers have to slowly and painstakingly search through the MLC’s Matching Tool to find unmatched recordings of their works.

MATCHING SOUND RECORDING TO MUSICAL WORK

Publishers and songwriters receive statutory mechanical royalties when recordings of their works are streamed or downloaded.

A significant part of The MLC’s mandated role is to match sound recordings to musical works in

its database. If a sound recording is not matched to a musical work, the publisher and songwriter do not receive mechanical royalties for that recording’s streams and downloads.

As an example of one kind of problem I’ve experienced with The MLC’s data, per The MLC,

“Unchained Melody” has been recorded by more than 30,000 performers. I would like to diligence those recordings by comparing The MLC’s data to my own data to confirm and track payments.

As part of my due diligence, I asked The MLC for a list of those sound recordings that The MLC

claims to have matched to the “Unchained Melody” composition. That type of list should be

exportable by The MLC for copyright owners and is available from other CMOs. However, The

MLC told me it was not possible for The MLC to export such a list. I was told if I had access to

the MLC’s vast data dump, then I could go find the information for my one song.

In order for publishers to perform mechanical royalty income tracking exercises, we must know

the International Standard Recording Code (ISRC) of the sound recording so we may confirm we have accurately been paid for the correct number of streams or downloads.

With a song like “Unchained Melody” and other very important and iconic American Songbook

songs, there are possibly hundreds, or thousands of new cover recordings released every year.

Publishers use various sources to identify and track royalties received (or not received) for streams and downloads of those recordings.

Fortunately, I do have access to The MLC’s data dump. I paid tens of thousands of dollars to create tech that allows me to compare data from The MLC and other sources in order to identify data gaps and errors. In order to get a sense of the quality of The MLC’s data, I queried The MLC data on behalf of various clients. For one well-known legacy song, 11% of the sound recording to composition matches were incorrect. For another, 20% of the sound recording to composition matches were incorrect. This is why I wanted to export a list of sound recording matches made by The MLC. I can’t be the only publisher who needs a streamlined, efficient way to access, view and analyze The MLC’s data.

THE BLACK BOX

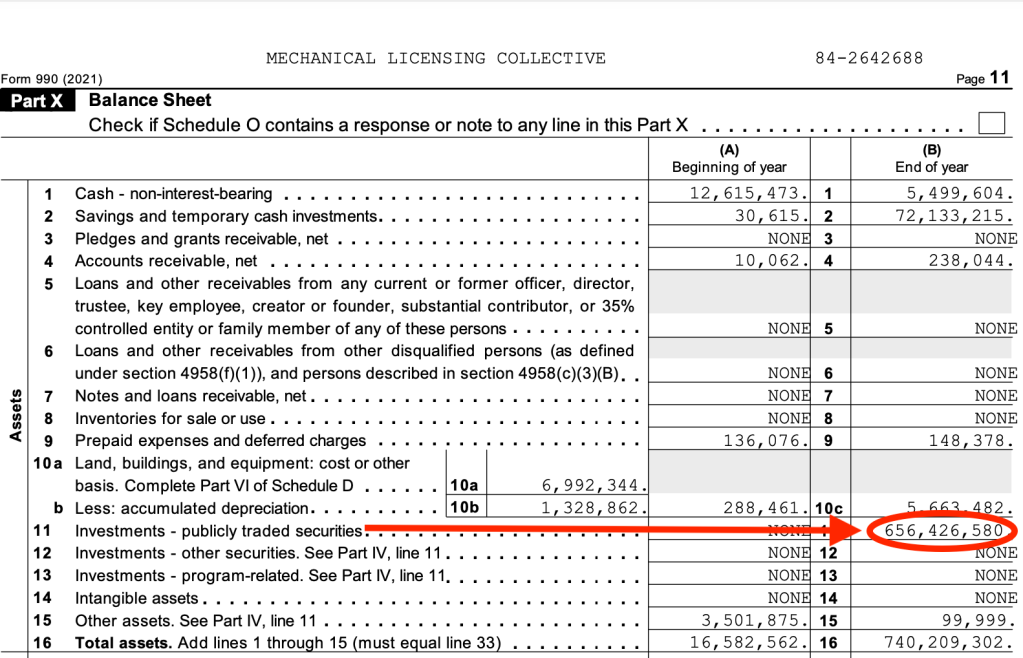

Prior to the inception of The MLC, the DSPs held approximately $424,000,000—that we know

of–in unallocated royalties, otherwise known as Black Box money. After the MMA passed, the

DSPs transferred that money to The MLC, which has held those monies and even more unallocated sums for years.

If I licensed my works to DSPs pre-MMA and if I now register my works with The MLC, my

money should not be in that Black Box. But sometimes I have co-publishers who deliver different data about our shared works that overwrites data I delivered. Sometimes I am unaware of a recording of my work, perhaps because it’s in a foreign language, or perhaps because as in Jamaica where “Unchained Melody” is popularly known as “Unchanged Melody” the recording has a known title permutation inconsistent with the US song title.

Foreign songwriters or songwriters from within the United States who are not affiliated with

established CMOs and/or who are unfamiliar with the registration process undoubtedly have

money in that Black Box. This is especially likely for songwriters who create in languages other

than English, such as Spanish-language songwriters.

Foreign language characters such as accents or tildes often come across as jumbled data on

reporting statements from The MLC. Asian characters may be extremely difficult to translate.

It is understandable that all collectives have some unidentified works and parties from time to time, but by statute, The MLC is mandated to aggressively work and create technology to reduce that Black Box significantly. The world is experiencing rapid growth and development of Artificial Intelligence talent and technology. AI and machine learning technology utilized and trained well could assist in making composition to sound recording matches and identification of works and their parties.

Some of the money that is referred to as “Black Box” is actually claimed and matched but has been held as The MLC awaits the final decision regarding CRB Phonorecords III rates and terms. These 2018 – 2022 royalties apparently will soon be distributed by The MLC. We must prevent the wrong parties from receiving these royalties. As per above, my own research showed recordings matched to the wrong musical works.

The MLC must develop or license and utilize the best technology, the best and most comprehensive data and extremely attentive human beings to improve its quality of data.

AGGREGATORS OPENING FLOODGATES OF BAD DATA

Another example of a recurring problem I have with the MLC involves misclaimed copyright

shares by independent, DIY artists, of which there are thousands. Sound recording distribution aggregators such as Tunecore and CDBaby have lowered the barrier for delivery to DSPs in a dramatic way. Today, approximately 100,000 recordings per day are distributed to the various DSPs.

However, in creating the unfettered opportunity for anyone to distribute a sound recording, these aggregators have also flooded the CMOs with incorrect musical work data.

It is an honor and a blessing to control a song that so many performers choose to record. However, it is time-consuming to constantly police the erroneous data provided by so many of these performers. This is particularly frustrating when I have already corrected the same data.

In order to deliver a sound recording via an aggregator, the label or independent artist is required to provide information regarding the musical works embodied in the sound recordings to be distributed. Even if that artist has no idea who the writer or publishers are, that artist must provide some data.

Giving them the benefit of the doubt, many of these independent artists are unfamiliar with the

fact that the sound recording copyright is different from the composition copyright, and they

regularly identify themselves as writer and copyright owner when they are neither, and then falsely assign publishing administration to the aggregator’s publishing services. The aggregator’s publishing administration provider then executes its administrative role and attempts to collect this infringing share.

At least on a monthly basis. I must play whack-a-mole, searching The MLC’s portal to find new

registrations of “Unchained Melody” that make no mention of Alex North as composer, Hy Zaret as lyricist, or of our publishing entities.

We, as an industry, must force some vetting and validation mechanism in between the aggregators and The MLC (and other CMOs) and the DSPs. Musical work data must not be delivered into the music ecosystem until it has been vetted and validated. Every American Songbook and most frequently covered song I have reviewed at The MLC has the same problem with infringing data delivered on behalf of unknowing independent artists, and

we need a solution.

When I claim these infringing registrations at The MLC, my underlying registration of “Unchained Melody” goes into suspense. Meaning, “Unchained Melody” is iconic and well-known worldwide, and our data is easily searchable at other CMOs who do know who the writers and publishers are.

Unfortunately, music publishers have to repeatedly fight for our rights and our data at The MLC.

This is not the gold standard. With all the promise and hope of The MLC, I expected that the US

collective would be at least as good as, if not better than, the best foreign CMO.

I suggest that some iconic musical works should have flags preventing the wrong parties from

making claims. For example, if the song was a hit written and performed by a band, that song’s

writers are widely known, and no other person should be able to submit a registration claiming

that work. If I try to claim I am a writer of the Mancini/Mercer composition, “Moon River,” The

MLC should be aware I have no rights to that work. Our precious American Songbook treasures

and their songwriters must be protected.

The MLC was presented as a savior to songwriters. With the passing of the MMA, songwriters

were promised they’d finally receive all the mechanical royalties they are entitled to. Protecting

the works created by songwriters is a powerful step in this direction.

It’s been three years and the MLC is a long way from best in class. In fact, US publishers are

engaging the Canadian collective CMRRA, for a fee, to fix their data problems at The MLC. In

my experience, I have never heard of one CMO cleaning another CMO’s data. And, the publishers are paying for this service despite promises to the contrary.

CLAIM OVERLAP/DISPUTE RESOLUTION

To make the above even more complicated, there is no claim overlap/dispute resolution portal

within The MLC’s website.

With tens of millions of dollars paid by the DSPs to The MLC for operations and technology

development, The MLC has the opportunity to create truly innovative products, including at least a basic claim overlap/dispute resolution portal. Other collectives, such as SoundExchange and CMRRA have functional claiming portals.

A claiming overlap/dispute resolution tool could allow the parties to upload documents

substantiating claims, could allow the parties to directly communicate via the portal and facilitate resolution.

In the “Moon River” example above, this claiming portal could have information about “Moon

River” and its writers and parties that alerts others they have no right to claim this work, and also indicates to The MLC that it must block the infringing new claim. Preventing the infringing claims from occurring in the first place would also prevent “Moon River’s” mechanical royalties from going into suspense.

MLC CREATING BUSINESS RULES THAT CONTRADICT EXISTING LAW AND

REGULATIONS AND CREATE DOUBLE STANDARDS

The US copyright law permits authors or their heirs, under certain circumstances, to terminate the exclusive or non-exclusive grant of a transfer or license of an author’s copyright in a work.

The ability to recapture rights via the United States copyright termination system truly provides

composers, songwriters and recording artists and their heirs, a “second bite of the apple.” Many of my clients exercise this right and subsequently become the original publisher in the United States.

The unilateral decision made by The MLC that rights held at the inception of the new blanket

license might remain, in perpetuity, with the original copyright grantee was frightening. Not

recognizing that the derivative work exception does not apply in the context of the mechanical

blanket license would unquestionably have benefited the major publishers who control the bulk of legacy copyrights. It would have harmed songwriters and their families.

Fortunately, the US Copyright Office stepped in clarify that the appropriate payee under the

mechanical blanket license to whom the MLC must distribute royalties in connection with a

statutory termination is the copyright owner at the time the work is used.

The MLC has made unilateral decisions regarding how it treats public domain works. It invoices

the DSPs for streams of recordings that embody these public domain works, but no publisher is

entitled to these royalties. That means the MLC may collect money it may not pay out. This

makes little sense.

CONCLUSION

Music publishing administration and collective management of rights are very challenging

businesses. I control one of the most iconic of all of the American Songbook works, but I am truly an independent publisher. I work for my family and the other heirs who use the royalties we receive from our musical works to pay for mortgages, college educations, and food. I realize that The MLC considers me to be annoying and difficult, but I am responsible for the livelihood of others, and I am responsible for keeping alive the legacies of Alex North, Hy Zaret and the many other legacy songwriters I represent.

As such, I will continue to push for The MLC to meet the promises made by the MMA.

As a songwriter advocate, it is so important to me that songwriters collect every penny they are

due. Without songwriters and the songs they create, there is no music business. Songs connect people, define eras and bring joy.

The MLC must use its resources to perform its mandated duty to create a truly authoritative,

accurate, comprehensive database. It must use its resources to identify unidentified works and

parties. And it must make sure the wrong parties do not receive songwriter royalties.

The MLC must not make unilateral decisions that affect the lives of songwriters and music

publishers. If there is a question regarding a law, regulation or internal policy, the US Copyright

Office must be consulted and must participate in the decision- or rule-making process to take

corrective action or refer a matter to someone who can.

The MMA does not authorize The MLC to make legal decisions. The MLC is not judge, not jury,

and not arbiter. Rather, it was created to be a neutral mechanical royalty pass-through entity.

On behalf of songwriters who were told The MLC was going to get them paid, The MLC must

engage every resource, every data set, every technique and technology available in order to identify the unidentified and the misidentified. The MLC has the money and it has the staffing.

The MLC simply must do the job the DSPs are paying it to do. Until these tasks are completed, songwriters are not only being ill-served, songwriters are being harmed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.