| Against Frozen Mechanicals | Supporting Frozen Mechanicals |

| Songwriters Guild of America | National Music Publishers Association |

| Society of Composers and Lyricists | Nashville Songwriters Association International |

| Alliance for Women Film Composers | |

| Songwriters Association of Canada | |

| Screen Composers Guild of Canada | |

| Music Creators North America | |

| Music Answers | |

| Alliance of Latin American Composers & Authors | |

| Asia-Pacific Music Creators Alliance | |

| European Composers and Songwriters Alliance | |

| Pan African Composers and Songwriters Alliance | |

| North Music Group | |

| Blake Morgan | |

| David Lowery | |

| ATX Musicians |

Category: Copyright

Professor Kevin Casini (@KCEsq) Asks Congress and the CRJs for Meaningful Public Comment on Frozen Mechanical Royalty Settement

May 27, 2021

| Senator Richard Blumenthal 90 State House Square Hartford, CT 06103 Senator Chris Murphy Colt Gateway 120 Huyshope Avenue, Suite 401 Hartford, CT 06106 | Hon. C.J. Jesse M. Feder Hon. J. David R. Strickler Hon. J. Steve Ruwe US Copyright Royalty Board 101 Independence Ave SE / P.O. Box 70977 Washington, DC 20024-0977 |

Senators Blumenthal and Murphy, and Honorable Judges of the Copyright Royalty Board:

I am a Connecticut resident, attorney, and law professor, and the views expressed here are mine, and not necessarily those of any local or state bar association, or any employer. I am an active participant in politics local, state, and federal. I am a registered non-affiliate in New Haven. And I need your attention for about ten minutes.

On May 18, 2021, a “Notice of Settlement in Principle” was filed by parties to the proceedings before the Copyright Royalty Board about its Determination of Royalty Rates and Terms for Making and Distributing Phonorecords.[1] That Notice was followed on May 25, 2021 by a Motion To Adopt Settlement Of Statutory Royalty Rates And Terms For Subpart B Configurations, filed by the NMPA, Sony, Universal and Warner and NSAI.[2] I write today in reference to that proposed settlement.

This settlement outlines the terms by which mechanical royalty[3] and download rates will remain locked at the current rate of 9.1¢. The same almost-dime for each copy of a work manufactured and distributed. The same almost-dime that it’s generated since 2006. A paltry sum to be certain but a far cry from the 2¢ royalty rate mechanical royalties imposed for the better part of seventy years.[4] Starting in 1977, Congress mandated that the mechanical royalty be increased incrementally until 2006 when the rate of 9.1¢ was achieved. And there it has remained.

This proposed private settlement would extend that 2006 freeze until 2027.

In March 2017, a precursor to Phonorecords IV found the Copyright Royalty Board ruling that interactive streaming services must pay more in mechanical royalties over the course of the next five years.[5] Surely more than a simple inflation adjustment, but nonetheless a sign that the CRB thought costs and values needed to become more aligned for streaming—which is paid by the streaming platforms unlike the physical and download mechanical which is paid by the record companies. Now comes Phonorecords IV, and a proposed settlement from the major publishers and their affiliated major labels. Before this proposal can be accepted by the CRB, I asked for the simple opportunity of public comment.

As you well know, in nearly all other administrative proceedings public comment is an integral and indispensable component of the process. To see that the CRB may allow for a public comment period by members of the public beyond the participants in the proceeding or parties to the settlement is a step in the right direction, and my hope is that this development will be broadcast far and wide so that the CRB, and in turn, Congress, may get a full picture of the status of mechanical royalty rates, especially from those that are historically underrepresented. “Public comments” should be comments by the public and made in public; not comments by the participants made publicly.

Let me back up and state that I have a great deal of respect and admiration for the work put into the landmark copyright legislation that came about at the end of 2018, and for those that made it happen. So too for the members of the CRB, and in this space, I thank those Judges for taking the time to read a letter from an adjunct law professor with no economic stake in the outcome, but rather an interest in, and duty of, candor to the Court.

In an age of unprecedented political polarization, the consensus built in the passage of the Music Modernization Act showed that politics aside, when it’s time to make new laws that fix old problems, Congress can still get the job done. I know well the sweat-equity poured into its creation by the very same people that propose this settlement. I have found myself on the same side fighting the same fight as them many times. They have proven capable of navigating your halls and taking on those that would seek to devalue (or worse) the work of the songwriter, and musician. In this instance, I would like to see them fight the fight yet again. recognize the reasoning and intention behind the proposed settlement. Comment by the public made publicly is a way for that to happen.[6]

Our state, Connecticut, has a long and storied history with music. In 1956, The Five Satins recorded what would go on to be one of the most recognizable and beloved doo-wop songs in history. “In The Still of the Night” was ranked 90th in Rolling Stone’s list of Top 500 songs of all time.[7] Five years later, the 1961 Indian Neck Folk Festival was where a young Bob Dylan’s first recorded performance.[8] That young man turned into a fine songwriter, as evidenced by the 4,000+ covers recorded of his works, and his record sale last year of his publishing royalties.[9] And no one will forget Jim Morrison’s arrest at the old New Haven Arena, December 1967. Ticket price: $5.00. Connecticut is home to more than 14,000 registered songwriters, only a small percentage of whom have engaged a music publisher. These writers are considered “self-publishing”, but the reality is, they have no publishing. Ironically, it is these independent writers who rely disproportionately on physical sales, direct downloads, and Bandcamp Fridays.[10]

A year ago, I made the unilateral decision to pivot our consulting company, Ecco Artist Services, to purposefully work with, and advocate for, the traditionally and historically underserved and underrepresented in the music industry. Freezing the growth of rates for physical and digital sales that are already digging out of the residual effects of 70 years at 2¢ strikes at the heart of that community’s ability to generate revenues from their music.

Sadly, rate freezes for mechanical royalties are nothing new. I’ll tell you what has not been frozen since 2006: the cost of living. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, prices for rent of primary residence were 53.49% higher in 2021 versus 2006 (a $534.91 difference in value). Between 2006 and 2021 rent experienced an average inflation rate of 2.90% per year. This rate of change indicates significant inflation. In other words, rent costing $1,000 in the year 2006 would cost $1,534.91 in 2021 for an equivalent purchase. Compared to the overall inflation rate of 1.82% during this same period, inflation for rent was higher.[11] Milk? How about 19.48%.[12] Childcare? In Connecticut? Senators, you don’t even want to know.[13]

Now, it’s no secret the trade association for the US music publishing industry is funded by its music publisher members, and of course, as a professional trade organization, the association is bound to represent those members. Publishers have long enjoyed a better reputation amongst industry insiders than “the labels,” and for good reason, but the fact remains that writers signed to publishing deals are in contractual relationships with their publishers, and their interests are not always aligned. Such is the state of play in a consumer-driven marketplace, and especially now that publishers and labels are consolidating their businesses under the same tents.

Unfortunately, the independent songwriter lacks the resources to participate fully in the process, and although a signed songwriter may believe her interests and those of her publisher are one and the same, they may not always be. It would seem the economic analysis the publishers undertook in deciding the mechanical royalty was not worth the heavy cost and burden of fighting is the same calculus the writers need not do: they couldn’t afford the fight no matter the decision.

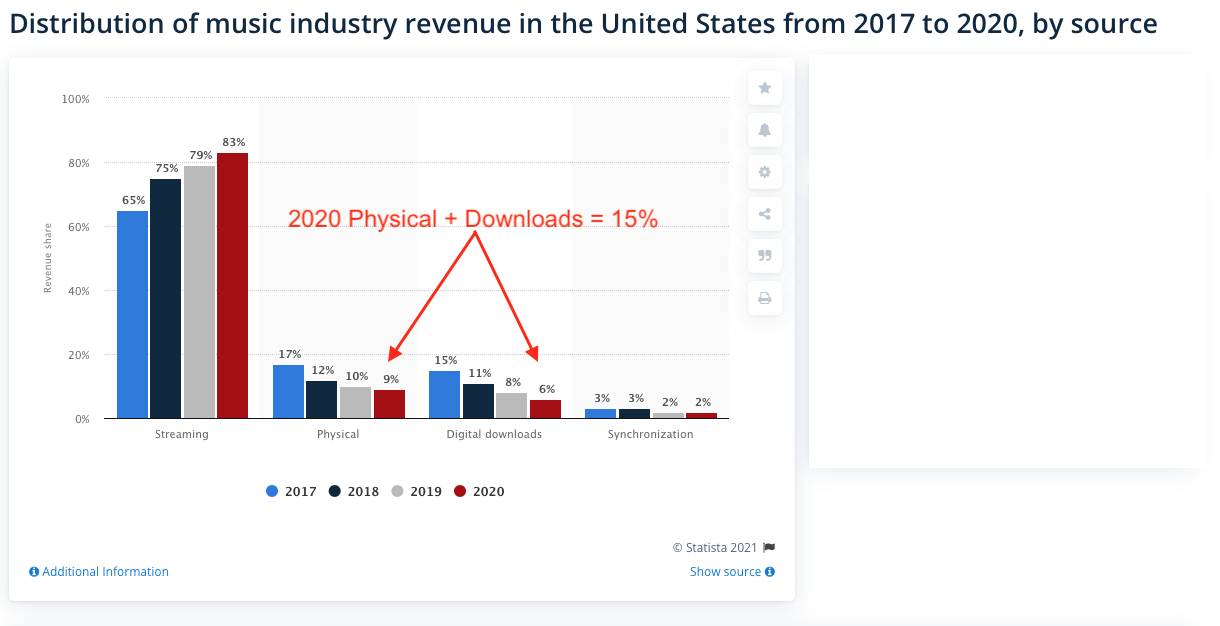

But I ask: if the mechanical royalty covered by the proposed settlement is a dying source of revenue, why would the fight be so onerous? By the RIAA’s 2020 year-end statistics, physical sales and downloads accounted for 15% of the music marketplace.[14] That’s a $12.2 billion marketplace, and that 15% amounts to $1.8 billion. Now, I know attorney’s fees can be exorbitant in regulatory matters, but I would think we could find a firm willing to take the case for less than that. As for sales, in 2020, 27.5 million vinyl LPs were sold in the United States, up 46-percent compared to 2019 and more than 30-fold compared to 2006 when the vinyl comeback began,[15] while some 31.6 million CD albums were sold.[16]

Median wages in the US, adjusted for inflation, have declined 9% for the American worker. Meanwhile, since the 9.1¢ rate freeze, the cost of living has gone up 31%, according to the American Institute of Economic Research[17]. The 2006 inflation rate was 3.23%. The current year-over-year inflation rate (2020 to 2021) is now 4.16%[18], which is all really to say, simply, an accurate cost-of-living increase would have a mechanical rate of at least 12¢ per sale. Twelve cents! You would think that would be an easy sell, but the streaming rates are fractions of that rate. The reality is a song would need to be streamed 250 times to generate enough money to buy it from iTunes. As my dear friend Abby North put it, the royalty amount for the digital stream of a song is a micro penny.[19]

An adjustment for inflation should require no briefing, let alone argument. If songwriters were employees, this would simply be line-item budgeted as a “cost-of-living adjustment.” If songwriters were unionized it would be a rounding error, but I digress.

A period and opportunity for the general public to comment publicly and on the record in these and other proceedings before the presentation to the CRB of this proposed settlement is in the interest of all involved. Even if it is true that the mechanical revenue is a lost and dying stream, by the RIAA’s own figures, there stand to be billions of dollars at stake. An opportunity to be heard, without having to sign with a publisher and then hope that publisher takes up the fight you want, maybe that’s all the independent writers of the industry—and, indeed, the world–need to be able to win.

In addition to a meaningful public comment period, and an inflation-adjusted cost-of-living update to the mechanical statutory royalty rate at issue, I’d ask that this letter be made a part of the Phonorecords IV public record and that you review the best practices of the Copyright Royalty Board. Not only so that those independent, self-published writers affected by its decision may voice their concerns through public comments that the CRB considers before it makes its final decision, but so that those of us that speak without financial stake in the matter can provide perspective from a policy and legal perspective.

I want to close by thanking the Board, and Copyright Office, the Judiciary Committee and the Intellectual Property Subcommittee, and the Copyright Royalty Board for their continued attention to the universe of copyright, licensing royalties, and the economy that exists therein. Lord knows there are lots of fires to be put out all over and the time spent and thought given to these policies is acknowledged and appreciated.

Kevin M. Casini

New Haven, CT

Attorney-at-Law, Adj. Professor, Quinnipiac Univ. School of Law

cc: Ms. Carla Hayden, US Librarian of Congress

Ms. Shira Perlmutter, US Register of Copyrights

[1] (Phonorecords IV) (Docket No. 21–CRB–0001–PR (2023–2027)).

[2] Available at https://app.crb.gov/document/download/25288

[3] The term “mechanical royalty” dates back to the 1909 Copyright Law when Congress deemed it necessary to pay a music publishing company for the right to mechanically reproduce a musical composition on a player-piano roll. As a result, music publishers began issuing “mechanical licenses”, and collecting mechanical royalties from piano-roll manufacturers. The times, and the tech, changed, but the name stuck.

[4] A summary of historical mechanical royalty rates is available from the U.S. Copyright Office at https://www.copyright.gov/licensing/m200a.pdf

[5] Docket No. 16-CBR-0003-PR (2018-2022) (Phonorecords III).

[6] The CRB arguably has the statutory obligation to publish the Motion in the Federal Register for public comment, but may have the discretion to construe those commenting to the participants in the proceeding and the parties to the settlement. 17 U.S.C. § 801(b)(7). It would be unfortunate if the Judges narrowly construed that rule to the exclusion of the general public, unlike the Copyright Office regulatory practice.

[7] “Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Songs of All Time”. Rolling Stone. April 2010.

[8] “Looking Way Back, As Bob Dylan Turns 60” Roger Catlin, Hartford Courant May 24, 2001

https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-xpm-2001-05-24-0105241174-story.html

[9] “Bob Dylan Sells His Songwriting Catalog in Blockbuster Deal” Ben Sisario, New York Times, December 7, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/07/arts/music/bob-dylan-universal-music.html

[10] Bandcamp Fridays Brought in $40 Million for Artists During Covid Pandemic Ethan Millman, Rolling Stone December 15, 2020

[11] https://www.officialdata.org/Rent-of-primary-residence/price-inflation/2006-to-2021?amount=1000

[12] https://www.in2013dollars.com/Milk/price-inflation/2006-to-2021?amount=4

[13] According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, prices for childcare and nursery school were 52.57% higher in 2021 versus 2006 (a $5,256.98 difference in value).

Between 2006 and 2021: Childcare and nursery school experienced an average inflation rate of 2.86% per year. This rate of change indicates significant inflation. In other words, childcare and nursery school costing $10,000 in the year 2006 would cost $15,256.98 in 2021 for an equivalent tuition. Compared to the overall inflation rate of 1.82% during this same period, inflation for childcare and nursery school was higher.

[14] RIAA year-end revenue statistics. https://www.riaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/2020-Year-End-Music-Industry-Revenue-Report.pdf

[15] MRC 202 Year End Report. https://static.billboard.com/files/2021/01/MRC_Billboard_YEAR_END_2020_US-Final201.8.21-1610124809.pdf

[16] Id.

[17] American Institute for Economic Research. https://www.aier.org/cost-of-living-calculator/

[18] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index https://www.officialdata.org/articles/consumer-price-index-since-1913/

[19] Abby North, North Music Group Letter to Congress on Frozen Mechanicals and the Copyright Royalty Board, The Trichordist (May 24, 2021) available at https://thetrichordist.com/2021/05/24/northmusicgroup-letter-to-congress-on-frozen-mechanicals-and-the-copyright-royalty-board/

Another Call for Congressional Oversight of the Proposed Settlement of Physical and Download Mechancials

[Editor T says pay close attention to Gwen Seale’s analysis of the side deal.]

Gwendolyn Seale, Esq.

May 26, 2021

The Hon. John Cornyn III

517 Hart Senate Office Building

Washington, DC 20510

The Hon. Ted Cruz

Russell Senate Office Building 127A

Washington, DC 20510

SENT VIA EMAIL

Re: Potential Settlement of Mechanical Royalty Rates in CRB Phonorecords IV

Dear Senators Cornyn and Cruz,

I am a music lawyer in Austin, Texas, and represent songwriters located throughout our great state. The views I express here are my own and are not on behalf of any of my clients or the State Bar of Texas.

I am contacting you as I am deeply troubled by the private party settlement of mechanical royalty rates pertaining to physical product and digital sales in the “Determination of Royalty Rates and Terms for Making and Distributing Phonorecords (Phonorecords IV)” currently pending before the Copyright Royalty Board (CRB).

Background / Historical Context

With the constant consumption of music occurring via the streaming services, many do not realize the degree of revenue generated from the sale of physical products (vinyl, CDs) and digital downloads in the United States. Notwithstanding the devastating pandemic which forced the majority of workers to pivot, and resulted in at the very least the temporary shutdown of a significant amount of businesses, revenue from the physical music sales amounted to $1.13 billion dollars in 2020 (YEAR-END 2020 RIAA REVENUE STATISTICS). Additionally, vinyl record sales increased by more than 28% from 2019 to 2020. Physical and downloads accounted for 15% of worldwide revenue for U.S. recorded music in 2020.

The current statutory mechanical royalty rate pertaining to physical products and digital downloads in the United States is 9.1 cents per song per record sold and has been so since 2006. To give some historical context, this statutory rate was frozen at 2¢ from 1909 to 1978. Congress mandated that the rate be incrementally increased beginning in 1978, following the passage of the 1976 Copyright Act, from 2¢ to the 9.1 ¢ minimum rate in 2006. Prior to the passage of the 1976 Copyright Act, this rate had been frozen at 2 cents for 69 years.

The participants in this current private party settlement request that the 9.1¢ rate remain frozen through 2027, which results in this rate remaining the same for over 20 years. Note that the mechanical royalties pertaining to physical product sales are paid to songwriters and publishers by record companies and not by streaming services. The Big 3 record companies also own the Big 3 music publishers who are the major members of the National Music Publishers Association, so the licensee record companies literally take the money for mechanicals out of one pocket and place it in the other—songs and recordings are tied together.

Mechanical royalties from physical product sales are a crucial revenue stream for independent songwriters – for Texan songwriters. In contrast, the mechanical royalty “rate” pertaining to streams on Spotify Premium during April 2020 amounted to $0.00059 per stream (according to the Audiam U.S. Mechanical rate calculator: https://resources.audiam.com/rates/ ). The “rate” for the ad-supported tier of Spotify was even lower. Note that the mechanical royalties pertaining to interactive streaming are paid by the streaming services. The streaming services are not parties to the private party settlement.

The Private Party Settlement

I find it important to provide the aforementioned context because there is a serious lack of education regarding copyright, the various royalty streams pertaining to music and the innerworkings of the music industry. And if you happen to be a songwriter, particularly a songwriter outside of the Los Angeles, New York or Nashville hubs, this education gap expands exponentially. So now, let us draw our attention to this private party settlement.

The initial area of my concern pertains to the participants requesting the settlement. On one side, you have the major record companies, consisting of Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment and Warner Music Group. On the other side, you have one trade organization, the NMPA, which represents certain music publishers, including publishing company affiliates of the major record companies (Universal Music Publishing Group, Sony Music Publishing, and Warner/Chappell Music Publishing) which companies have representation on the board of the NMPA. You also have another trade organization, the Nashville Songwriters Association International, which represents a fragment of the songwriter community. This unequivocally presents a conflict of interest: how can songwriters be adequately represented when one of the two parties to the settlement, which are claims to advocate for the songwriters and publishers, is comprised of affiliated major record companies on the opposite side of the negotiation? The Trichordist asked the question—if the willing buyer and the willing seller are the same person, is that a free market?

The settlement participants stated the following in MOTION TO ADOPT SETTLEMENT OF STATUTORY ROYALTY RATES AND TERMS FOR SUBPART B CONFIGURATIONS, Docket No. 21-CRB-0001-PR (2023–2027) at 4:

“And because the Settlement represents the consensus of buyers and sellers representing the vast majority of the market for “mechanical” rights for [physical, permanent downloads, ringtones and music bundles]…”

This settlement does not represent the consensus of songwriters; this settlement represents “buyers” and “sellers” who are one in the same at the corporate level.

Songwriters should have been included in these negotiations from the outset. But, at the bare minimum, parties to transactions involving the fate of this critical revenue stream for songwriters should be transparent to the people they purport to represent. Neither of the foregoing are occurring. Only after the circulation of a rash of articles concerning this issue did the settlement participants respectfully request that the CRB post the royalty rates and terms of the settlement in the Federal Register for public notice and comment.

There are plenty of organizations that represent our country’s songwriters which could provide feedback and suggestions without the presence of conflict, and it is simply disingenuous to ask those parties for their comments following a settlement being presented to the CRB for adoption as a done deal. Any public comments are and will be utterly predictable; songwriter advocates simply ask for an increase in this mechanical rate. Songwriter advocates foresee history repeating itself, with an increase in this rate occurring sometime around this country’s Tri-centennial.

Transparency equates to honesty, and on the flip side of the coin, a lack of transparency leads to distrust. As such, along with providing my concerns about the nature of this settlement, and the dire need for honesty in connection with settlements that affect every Texan songwriter and every songwriter in this country, I request that you press the CRB to request that the settlement parties disclose not only the actual settlement agreement (not just the regulations giving effect to the settlement) but also the “Memorandum of Understanding” referenced in MOTION TO ADOPT SETTLEMENT OF STATUTORY ROYALTY RATES AND TERMS FOR SUBPART B CONFIGURATIONS, Docket No. 21-CRB-0001-PR (2023–2027) at 3.

“Concurrent with the settlement, the Joint Record Company Participants and NMPA have separately entered into a memorandum of understanding addressing certain negotiated licensing processes and late fee waivers.”

If this “Memorandum of Understanding” was irrelevant to this settlement, the language would not have been included in this motion filed by the settlement participants. Setting aside the broadly drafted “certain negotiated licensing processes,” the phrase “late fee waivers” is exceptionally concerning, given the aforementioned context. It sounds like money is changing hands and it is consideration for the frozen mechanical—but only for a select few who were invited to the multi-tiered negotiation.

Thank you for your time and I am more than happy to discuss these issues with you anytime.

Best Regards,

Gwendolyn Seale

@CMU and @billboard Cover the Songwriter Coalition and Opposition to Frozen Mechanicals

Complete Music Update in the UK picked up the story on the songwriter coalition letters to the Copyright Royalty Board that we have previously posted on Trichordist so you can read them in full. Read it here: Songwriter groups urge US Copyright Royalty Board to open submissions on proposed new mechanical royalty rate on discs and downloads. CMU makes this important point:

While the publishers and songwriters are generally of one mind when it comes to the streaming mechanical rates, plenty of organisations representing songwriters in the US and beyond are not happy with what the NMPA and NSAI are proposing regarding the rate for discs and downloads.

That is right on because you don’t have to be against the streaming royalty to be against frozen mechanicals on physical and downloads. Why? What David said:

It also looks like the songwriters coalition and the beginnings of press may have done the trick! Today the NMPA filed their motion to ask the CRB to adopt the frozen mechanicals. Which raises the question of if a willing buyer and a willing seller are the same person, does that equal a free market?

Filing the motion isn’t the end of the story or even the end of the beginning because they failed miserably to take into account the dissatisfaction with the whole idea of a frozen mechanical. AND the motion contains this sentence:

Concurrent with the settlement, the Joint Record Company Participants and NMPA have separately entered into a memorandum of understanding addressing certain negotiated licensing processes and late fee waivers.

That sounds like there’s a separate deal on the actual money. The motion doesn’t attach either the settlement or the side deal (which may be where the money is) just the draft changes to the royalty regulations that freezes the mechanical for the rubes. That kind of defeats the purpose of having a motion for public comment on a deal that the public doesn’t see. (And maybe not even the judges.)

Billboard also covered the songwriter coalition letters to CRB in Songwriter Groups Want Their Voices Heard on CRB Royalty Rate ASAP.

Everyone should appreciate the coalition for apparently prompting the motion (which was expected to have been filed back on May 18 according to the CRB letter). It remains to be seen if the motion is worth commenting on or is just more secret sauce. Maybe the CRB can get the right information on file so that songwriters know what’s going on and know what they are getting bound to.

Copyright Royalty Board Responds to Coalition of Songwriter Groups on Frozen Mechanicals

A group of songwriter organizations from around the world wrote to the Copyright Royalty Board last week opposing a proposed private “settlement” between the major labels and the major publishers to freeze mechanical rates on physical and downloads at the 9.1¢ 2006 rate that was filed in the current Copyright Royalty Board (CRB) rate court hearing called “Phonorecords IV”. (You can find the entire list of filings in the case here.)

The twist here is that if the CRB approves the private settlement at the request of “the parties” and doesn’t take into account the views and evidence of people who actually write songs and have to earn a living from songwriting, it will be grotesquely unfair and possibly unconstitutional wage and price control. The CRB will have frozen the mechanical rate for physical and downloads at the 2006 rate when inflation alone has eaten away the buying power of that royalty by approximately 30%. This would be like the Minerals Management Service adopting a settlement written by Exxon.

On average–on average–the physical and download configuration make up 15% of billing for the majors and for some artists vinyl is a welcome change from fractions of a penny on streaming. And then there’s Record Store Day–hello? These are a couple of the many reasons anyone who is paying attention should reject the terms of the settlement.

The Coalition had a simple ask: Let the public comment:

In the interests of justice and fairness, we respectfully implore the CRB to adopt and publicize a period and opportunity for public comment on the record in these and other proceedings,especially in regard to so-called proposed “industry settlements” in which creators and other interested parties have had no opportunity to meaningfully participate prior to their presentation to the CRB for consideration, modification or rejection. In the present case, hundreds of millions of dollars of our future royalties remain at stake, even in a diminished market for traditional, mechanical uses of music. To preclude our ability to comment on proposals that ultimately impact our incomes, our careers, and our families, simply isn’t fair.

The Copyright Royalty Board responded! According to our sources, the Copyright Royalty Board said that they would publish the private settlement in the Federal Register and give the pubic the chance to comment. This is great news!

But we will see what they actually do. The Copyright Royalty Board does not have a great track record in understanding songwriter interests in raising the mechanical rates as we can see in this except from their final rule freezing mechanicals again in 2009:

Copyright Owners’ argument with respect to this objective is that songwriters and music publishers rely on mechanical royalties and both have suffered from the decline in mechanical income. Under the current rate, they contend, songwriters have difficulty supporting themselves and their families. As one songwriter witness explained, “The vast majority of professional songwriters live a perilous existence.” [Rick] Carnes [Testimony] at 3. [Rick Carnes signed the Coalition letter as President of the Songwriters Guild of America.] We acknowledge that the songwriting occupation is financially tenuous for many songwriters. However, the reasons for this are many and include the inability of a songwriter to continue to generate revenue-producing songs, competing obligations both professional and personal, the current structure of the music industry, and piracy. The mechanical rates alone neither can nor should seek to address all of these issues.

We simply do not accept that the Founders put the Copyright Clause in the Constitution so creators could have a side hustle for their Uber driving which is exactly where frozen mechanicals take you, particularly after the structural unemployment in the music business caused by the COVID lockdowns.

Here is a summary of who is for and who is against frozen mechanicals.

| Against Frozen Mechanicals | Proposing Frozen Mechanicals |

| Songwriters Guild of America | National Music Publishers Association |

| Society of Composers and Lyricists | Nashville Songwriters Association International |

| Alliance for Women Film Composers | |

| Songwriters Association of Canada | |

| Screen Composers Guild of Canada | |

| Music Creators North America | |

| Music Answers | |

| Alliance of Latin American Composers & Authors | |

| Asia-Pacific Music Creators Alliance | |

| European Composers and Songwriters Alliance | |

| Pan African Composers and Songwriters Alliance |

Which side are you on? If you want to write your own comment to the Copyright Royalty Board about frozen mechanicals, send your comment to crb@loc.gov

Coalition of Songwriter Groups Call on Copyright Royalty Board for Fairness and Transparency on Frozen Mechanicals

[Editor T says this is a letter from a coalition of US and international songwriter groups to the Copyright Royalty Board about the frozen mechanical issue. If you want to write your own comment to the Copyright Royalty Board about frozen mechanicals, send your comment to crb@loc.gov]

MUSIC CREATORS

NORTH AMERICA

May 17, 2021

Via Electronic Delivery

Chief Copyright Royalty Judge Jesse M. Feder

Copyright Royalty Judge David R. Strickler

Copyright Royalty Judge Steve Ruwe

US Copyright Royalty Board

101 Independence Ave SE / P.O. Box 70977

Washington, DC 20024-0977

To Your Honors:

As a US-led coalition representing hundreds of thousands of songwriters and composers from across the United States and around the world, we are writing today to express our deep concerns over the “Notice of Settlement in Principle” recently filed by parties to the proceedings before the Copyright Royalty Board concerning its Determination of Royalty Rates and Terms for Making and Distributing Phonorecords (Phonorecords IV) (Docket No. 21–CRB–0001–PR<(2023–2027)). For reasons explained below, several highly conflicted parties to this proceeding have apparently agreed to propose a rolling forward to the year 2027 of the current US statutory mechanical royalty rate for the use of musical compositions in the manufacture and sale of physical phonorecords (such as CDs and vinyl records). This proposal (and related industry agreements yet to be disclosed by the parties— see, https://app.crb.gov/document/download/23825) should neither be acted upon nor accepted by the CRB without the opportunity for public comment, especially by members of the broad community of music creators for whom it is financially unfeasible to participate in these proceedings as interested parties. It is our livelihoods that are at stake, and we respectfully ask to be heard even though we lack the economic means to appear formally as parties. If procedures are already in place to accommodate this request, we look forward receiving the CRB’s instructions as to how to proceed.

The current U.S statutory mechanical rate for physical phonorecords is 9.1 cents per musical composition for each copy manufactured and distributed. That rate has been in effect since January 1, 2006. It represents the high-water mark for US mechanical royalty rates applicable to physical products, a rate first established in 1909 at 2 cents. That 2-cent royalty rate, in one of the most damaging and egregious acts in music industry history, remained unchanged for an astonishing period of sixty-nine years, until 1978. Nevertheless, the recording industry now seeks to repeat that history by freezing the 9.1 cent rate for an era that will have exceeded twenty years by the end of the Phonorecords IV statutory rate setting period.

Inflation has already devalued the 9.1 cent rate by approximately one third. By 2027, 9.1 cents may be worth less than half of what it was in 2006. How can the US music publishing industry’s trade association, and a single music creator organization (which represents at most only a tiny sliver of the music creator community) have agreed to such a proposal?

The answer to that question is an easy one to surmise. The three major record companies who negotiated the deal on one side of the table have the same corporate parents as the most powerful members of the music publishing community ostensibly sitting on the other side of the table. Songwriter, composer and independent music publisher interests in these “negotiations” were given little if any consideration, and the proposed settlement was clearly framed without any meaningful consultation with the wider independent music creator and music publishing communities, both domestically and internationally.

How on earth can these parties be relied upon to present a carefully reasoned, arms-length “Settlement in Principle” proposal to the CRB under such circumstances, fraught as they are with conflicts of interest, without at least an opportunity for public comment? Further, how can these parties be relied upon in the future to argue persuasively that mechanical royalty rates applicable to on-demand digital distribution need to be increased as a matter of economic fairness (which they most certainly should be), when they refuse to seriously conduct negotiations on rates applicable to the physical product the distribution of which is still controlled by record companies (who not so incidentally also receive the lion’s share of music industry revenue generated by digital distribution of music)?

The ugly precedent of frozen mechanical royalty rates on physical product has, in fact, already served as the basis for freezing permanent digital download royalty rates since 2006. Is this the transparency and level playing field the community of songwriters and composers have been promised by Congress through legislation enacted pursuant to Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution?

The trade association for the US music publishing industry is supported by the dues of its music publisher members, the costs of which are often in large part passed along to the music creators affiliated with such publishers. It is thus mainly the songwriter and composer community that pays for the activities of that publisher trade association, a reality that has existed since that organization’s inception. Still, the genuine voice of those songwriters and composers is neither being sought nor heard. Further in that regard, we wish to make it emphatically clear that regardless of how the music publishing industry and its affiliated trade associations may present themselves, they do not speak for the interests of music creators, and regularly adopt positions that are in conflict with the welfare of songwriters and composers. Their voice is not synonymous with ours.

Unfortunately, the music creator community lacks the independent financial resources –in the age of continuing undervaluation of rights, rampant digital piracy and pandemic-related losses–to rectify these inequities by expending millions more dollars to achieve full participation in CRB legal and rate-setting proceedings. Clearly, such an inequitable situation is antithetical to sound Governmental oversight in pursuit of honest and equitable policies and results.

In the interests of justice and fairness, we respectfully implore the CRB to adopt and publicize a period and opportunity for public comment on the record in these and other proceedings,especially in regard to so-called proposed “industry settlements” in which creators and other interested parties have had no opportunity to meaningfully participate prior to their presentation to the CRB for consideration, modification or rejection. In the present case, hundreds of millions of dollars of our future royalties remain at stake, even in a diminished market for traditional, mechanical uses of music. To preclude our ability to comment on proposals that ultimately impact our incomes, our careers, and our families, simply isn’t fair.

Finally, we request that this letter be made a part of the public record of the Phonorecords IV

proceedings. We extend our sincere thanks for your attention to this very difficult conundrum

for music creators, and further note that your consideration is very much appreciated.

Respectfully submitted,

Rick Carnes

President, Songwriters Guild of America

Ashley Irwin

President, Society of Composers and Lyricists

Officer, Music Creators North America Co-Chair, Music Creators North America

List of Supporting Organizations

Songwriters Guild of America (SGA), https://www.songwritersguild.com/site/index.php

Society of Composers & Lyricists (SCL), https://thescl.com

Alliance for Women Film Composers (AWFC). https://theawfc.com

Songwriters Association of Canada (SAC), http://www.songwriters.ca

Screen Composers Guild of Canada (SCGC), https://screencomposers.ca

Music Creators North America (MCNA), https://www.musiccreatorsna.org

Music Answers (M.A.), https://www.musicanswers.org

Alliance of Latin American Composers & Authors (ALCAMusica), https://www.alcamusica.org

Asia-Pacific Music Creators Alliance (APMA), https://apmaciam.wixsite.com/home/news

European Composers and Songwriters Alliance (ECSA), https://composeralliance.org

Pan-African Composers and Songwriters Alliance (PACSA), http://www.pacsa.org

cc: Ms. Carla Hayden, US Librarian of Congress

Ms. Shira Perlmutter, US Register of Copyrights

Mr. Alfons Karabuda, President, International Music Council

Mr. Eddie Schwartz, President, MCNA and International Council of Music Creators (CIAM)

The MCNA Board of Directors

The Members of the US Senate and House Sub-Committees on Intellectual Property

Charles J. Sanders, Esq.

Guest Post: The Supreme Court Should See Through Google’s Industrial-Strength Fair Use Charade

[This post first appeared on Morning Consult. The US Supreme Court will hear oral argument in the Google v. Oracle case on October 7]

Google’s appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court of two Federal Circuit decisions in Oracle’s favor is turning into the most consequential copyright case of the court’s term — if not the decade. The appeal turns in part on whether the Supreme Court will uphold the Federal Circuit’s definition of fair use for creators and reject Google’s dubious assertion of “industrial strength” fair use.

I co-wrote an amicus brief on the fair use question on behalf of independent songwriters supporting Oracle in the appeal. Our conclusion was that the Supreme Court should affirm the Federal Circuit’s extensive analysis and hold for Oracle because Google masks its monopoly commercial interest in industrial-strength fair use that actually violates fair use principles.

The story begins 15 years ago. Google had a strategic problem. The company had focused on dominating the desktop search market. Google needed an industrial-strength booster for its business because smartphones, especially the iPhone, were relentlessly eating its corporate lunch. Google bought Android Inc. in 2005 to extend its dominance over search — some might say its monopoly — to these mobile platforms. It worked — Android’s market share has hovered around 85 percent for many years, with well over 2 billion Android devices.

But how Google acquired that industrial boost for Android is the core issue in the Oracle case. After acquiring Android, Google tried to make a license deal for Sun Microsystems’ Java operating system (later acquired by Oracle). Google didn’t like Sun’s deal. So Google simply took a verbatim chunk of the Java declaring code, and walled off Android from Java. That’s why Google got sued and that’s why the case is before the court. Google has been making excuses for that industrial-strength taking ever since.

Why would a public company engage in an overt taking of Oracle’s code? The same reason Willie Sutton robbed banks. Because that’s where the money is. There are untold riches in running the Internet of Other People’s Things.

Google chose to take rather than innovate. Google’s supporters released a study of the self-described “fair use industries” — an Orwellian oxymoron, but one that Google firmly embraces. Google’s taking is not transformative but it is industrial strength.

We have seen this movie before. It’s called the value gap. It’s called a YouTube class-action brought by an independent composer. It’s called Google Books. It’s called 4 billion takedown notices for copyright infringement. It’s called selling advertising on pirate sites like Megaupload (as alleged in the Megaupload indictment). It’s called business as usual for Google by distorting exceptions to the rights of authors for Google’s enormous commercial benefit. Google now positions itself to the Supreme Court as a champion of innovation, but creators standing with Oracle know that for Google, “innovation” has become an empty vessel that it fills with whatever shibboleth it can carelessly manipulate to excuse its latest outrage.

Let’s remember that the core public policy justification for the fair use defense is to advance the public interest. As the leading fair use commentator Judge Pierre Leval teaches, that’s why fair use analysis is devoted to determining “whether, and how powerfully, a finding of fair use would serve or disserve the objectives of the copyright.” You can support robust fair use without supporting Google’s position.

Google would have the court believe that its fair use defense absolves it from liability for the industrial-strength taking of Oracle’s copyright — because somehow the public interest was furthered by “promoting software innovation,” often called “permissionless innovation” (a phrase straight out of Orwell’s Newspeak). Google would have the court conflate Google’s vast commercial private interest with the public objectives of copyright. Because the internet.

How the Supreme Court rules on Google’s fair use issue will have wide-ranging implications across all works of authorship if for no other reason than Google will dine out for years to come on a ruling in its favor. Photographers, authors, illustrators, documentarians — all will be on the menu.

Despite Google’s protestations that it is really just protecting innovation, what is good for Google is not synonymous with what is good for the public interest — any more than “what’s good for General Motors is good for America,” or more appropriately, “what’s good for General Bullmoose is good for the USA.”

Copyright Office Regulates @MLC_US: Selected Public Comments on MLC Transparency: @KerryMuzzey

[Editor Charlie sez: The U.S. Copyright Office is proposing many different ways to regulate The MLC, which is the government approved mechanical licensing collective under MMA authorized to collect and pay out “all streaming mechanicals for every song ever written or that ever may be written by any songwriter in the world that is exploited in the United States under the blanket license.” The Copyright Office is submitting these regulations to the public to comment on. The way it works is that the Copyright Office publishes a notice on the copyright.gov website that describes the rule they propose making and then they ask for public comments on that proposed rule. They then redraft that proposed rule into a final rule and tell you if they took your comments into account. They do read them all!

The Copyright Office has a boatload of new rules to make in order to regulate The MLC. (That’s not a typo by the way, the MLC styles itself as The MLC.) The comments are starting to be posted by the Copyright Office on the Regulations.gov website. “Comments” in this world are just your suggestions to the Copyright Office about how to make the rule better. We’re going to post a selection of the more interesting comments.

There is still an opportunity to comment on how the Copyright Office is to regulate The MLC’s handling of the “black box” or the “unclaimed” revenue. You can read about it here and also the description of the Copyright Office Unclaimed Royalties Study here. It’s a great thing that the Copyright Office is doing about the black box, but they need your participation!]

Read the comment by Kerry Muzzey

The launch of iTunes in 2001 began the democratization of music distribution: suddenly independent artists had a way to reach their fans without having to go through the traditional major label gatekeepers. Unfortunately most of those independent artists didn’t have a music business background to inform them about all of the various (and very arcane) royalty types and registrations that were required: and even if they did, Harry Fox didn’t let individual artists register for mechanicals until only recently.

The result? 19 years’ worth of unclaimed royalties by so many independent artists who have no idea how to access them.

We had hoped that the MMA would fix this, but the “black box” of unclaimed royalties is going to be distributed to the major publishers based on market share. We independent artists don’t have “market share” – but we do have sales and streams that are significant enough to make a difference to our own personal economies. A $500 unclaimed royalty check is to an independent musician what a $100,000 unclaimed royalty check is to a major publisher: it matters. Those smaller unclaimed royalty amounts are pocket change or just an inconsequential math error to the majors but they’re the world to an independent writer/publisher. And that aside, these royalties don’t belong to the majors: they belong to the creators whose work generated them.

Please, please, please: you have to make that database publicly accessible and searchable like Soundexchange does. There needs to be a destination where all of us can point our friends and social media followers to, to say “you may have unclaimed royalties here: go search your name.” They can’t remain in the black box and they can’t go to the major publishers. These royalties must remain in escrow and all means necessary should be used to contact the writers and publishers whose royalties are in that black box: absolute transparency is required here, as is a concentrated press push by the MLC to all of the music trades and music blogs (Digital Music News, Hypebot, et al) and social media platforms encouraging independent artists to go to the public-facing database and search their name, their publisher name, their band name, and by song title, for possible unclaimed royalties.

Please: the NMPA can’t be allowed to hijack royalties that do not belong to them. Publishers are fully aware of how complex royalty types and royalty collections are: they and the NMPA must make every effort here to ensure that unclaimed royalties reach their rightful legal and moral recipients.

How Spotify (and others) Could Have Avoided Songwriter Lawsuits, Ask The Labels.

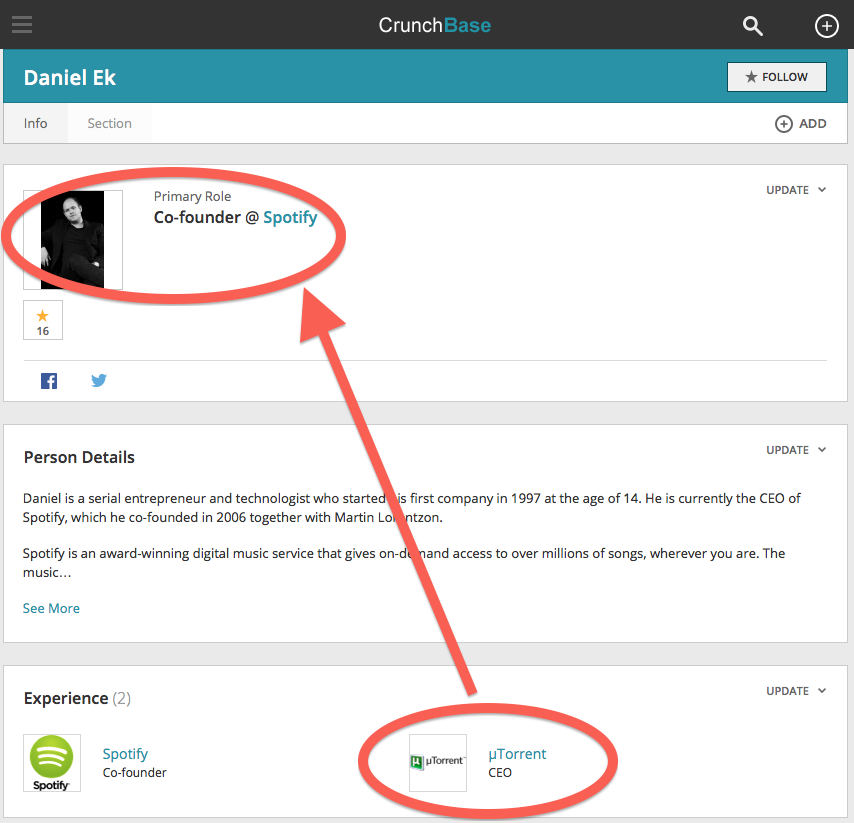

This is simply a story about intent. Daniel Ek is the co-founder of Spotify, he was also the CEO of u-torrent, the worlds most successful bit-torrent client. As far we know u-torrent has never secured music licenses or paid any royalties to any artists, ever.

Spotify could have completely avoided it’s legal issues around paying songwriters. The company could have sought to obtain the most recent information about the publishing and songwriters for every track at the service. The record labels providing the master recordings to Spotify are required to have this information. All Spotify (and others) had to do, was ask for it.

Here’s how it works.

For decades publishers and songwriters have been paid their share of record sales (known as “mechanicals”) by the record labels in the United States. This is a system whereby the labels collect the money from retailers and pay the publishers/songwriters their share. It has worked pretty well for decades and has not required a industry wide, central master database (public or private) to administer these licenses or make the appropriate payments.

This system has worked because each label is responsible for paying the publishers and songwriters attached to the master recordings the label is monetizing. The labels are responsible for making sure all of the publishers and writers are paid. If you are a writer or publisher and you haven’t been paid, you know where the money is – it is at the record label.

Streaming services pay the “mechanicals” at source which are determined by different formulas and rules based upon the use. For example non-interactive streaming and web radio (simulcasts and Pandora) are calculated and paid via the appropriate performing rights society like ASCAP or BMI. These publishing royalties are treated more like radio royalties.

The “mechanicals” for album sales from interactive streaming services are calculated in a different way. It is the responsibility of the streaming services to pay these royalties. CDBaby explains the system here and here. Don’t mind that these explanations are an attempt to sell musicians more CDBaby services, just focus on the information provided for a better understanding of this issue.

Every physical album and transactional download (itunes and the like) pays the “mechanical” publishing to the record label directly, who then pays the publishers and writers. This publishing information exists as labels providing the master recordings to Spotify have this information. All Spotify (and others) have to do, is ask for it.

Record labels have collectively and effectively “crowd sourced” licensing and payments to publishers and songwriters for decades. Why can’t Spotify simply require this information from labels, when the labels deliver their masters? It’s just that simple. Period.

The simple, easy, and transparent solution to Spotify’s licensing crisis is to require record labels to provide the mechanical license information on every song delivered to Spotify. The labels already have this information.

The simple solution is for Spotify to withdraw any and all songs from the service until the label who has delivered the master recording also delivers the corresponding publisher and writer information for proper licensing and payments. Problem solved!

No need for additional databases or imagined licensing problems. Every master recording on Spotify is delivered by a record label. Every record label is required by law to pay the publishers and songwriters. This is known and readily available information by the people who are delivering the recordings to Spotify!

There is no missing information, and no unknown licenses. Why is this so F’ing hard?

This system would mean that the record labels would have to provide this information. It’s also possible that some of that information is not accurate. Labels would probably fight against any mechanism that would make them have to make any claims about the accuracy of their data, which is fine. If it’s the most update information it’s a great place to start.

Of course, we know that both sides (both labels and streamers) will reject any mechanism that introduces friction into the delivery of masters. However, with the simple intent of requiring publisher and songwriter info for every song master delivered there will no longer be a problem at the scale that currently exists.

To be completely fair to Spotify they did work to make deals with the largest organizations representing publishers and songwriters (NMPA and HFA). However those two organizations leave out a lot of participants. So back to square one. If publishing information is required upon the delivery of masters, the problem is largely solved. Invoking a variation on Occam’s Razor, the best solution is usually the most simple one.

You’d think that in the times before computers this would have been harder than it is now, but like all things Spotify you have to question the motivations of a company whose founder created the most successful bittorrent client of all time, u-torrent.

Oh, and of this writing Spotify is now claiming they have no responsibility to pay any “mechanicals” at all. Can’t make this up.

California’s Other Drought: The Coming Ad Revenue Crisis

Guest Post By Alan Graham

Last month I published this piece over on LinkedIn, but I felt it might need a second viewing (with updates) over here based on recent news on ad blocking and other developments.

————–

Silicon Valley has a drought problem. But it isn’t the lack of water I’m concerned about. It is the over reliance on ad revenue and venture capital that is sustaining both tech and media. Now there’s a debate raging about whether or not we’re in another bubble (I was in the last one). The pro-bubble argument is often about overvaluations and spending. The anti-bubble argument shows charts on how VC investments and IPOs are much lower than the last one. Both sides completely miss the mark which is that since Google (er…Alphabet) and others began building empires on “freemium” type services, we’ve become accustomed to not having to pay for things, and what began with a tool here and there and some “free” content has actually become the predominant method of generating revenue across the web.

A possible disaster.

For the past two years I’ve been working on a project called OCL. One thing it does is it is the world’s first true microlicensing platform for apps that allows the merging of any creative asset with any other creative asset with all of the rights cleared “faster than instantly.” Yes…that’s possible. And it is actually built upon the idea of paying for things (a novel idea these days I know). I’ve run into a lot of resistance over this model to the point where I recently had an argument with a music journalist who saw no problem with the idea that advertising was a viable long term model of revenue and my predictions/concerns over a non-sustainable ad market (for everything) was silly.

I’ve also had many a meeting with executives who told me countless times that the punter won’t pay for anything. Their business model is to license large platforms and take a cut of ad revenue. During this time I’ve pointed out that with a finite amount of ad revenue that must be shared across all creative industries and tech platforms (all vying for attention), it simply is not possible to sustain a vibrant creative marketplace that requires ad revenue to keep it chugging along. And if those platforms have their revenue somewhat interrupted, that trickles down.

The reasons for being concerned are clear:

-ContentID was a anomaly born out of necessity to bring some order to a chaotic system of copyright infringement and push the biggest piracy site into some form of legitimacy.

-YouTube went from a method of promotion, to a method of generating much needed revenue, to cannibalizing sales of media, as there was no reason to purchase what you were already viewing/listening to.

-Ad revenue (CPCs) have been dropping year over year for the past 5 or so years, while volume continues to increase.

-Volume is increasing because there are simply more and more locations to place ads in an increasingly competitive market with a finite amount of ad dollars that simply shift from one point to another depending on popularity. Companies with ad budgets don’t suddenly spend more money because there are more locations to spend it. And quite frankly…volume is practically infinite.

-Increase in volume means a competitive marketplace that can drive CPC and other ad rates down further because we’re witnessing something happening to ads that happened to media, commoditization. All about numbers at this point, not quality of creative.

-We’re just getting started. Estimated reach/penetration of iOS/Android/FB is anywhere from 5M to 9M apps/platforms with 40k apps being added to iTunes each month alone. Reports show that the range of “free” apps is somewhere around 90%, both ad supported and in-app purchases. As that tail grows, so does volume.

-86%+ of our time accessing the web is now done through apps.

-Ad networks and other ad-based companies are going to get squeezed out of existence because of this, causing a collapse of an entire segment of tech which means thousands of high paying jobs are gonna go bye-bye and never come back. This is already starting to happen.

-Ad revenue is currently 80%+ of all revenue generated by Facebook and Google, two of the most important platforms for media distribution. It keeps their lights on and it is this revenue creators hitched their wagons to.

-Media companies (music, news, video, images) are scrambling to get a cut of that same ad revenue and finding they not only are competing for that money, they often have to spend money towards making that money back. Welcome to the world of paid non-organic reach. You now work for the company, live in company housing, and shop at the company store.

-Ad blocking is starting to take off in popularity and in court cases the judges in two instances sided with the ad blocking company stating that the user gets to decide what they want to do with their devices.

“Online ad blocking costs sites nearly $22 billion

The study, by software group Adobe and Ireland-based consultancy PageFair, found that the number of Internet users employing ad-blocking software has jumped 41 percent in the past 12 months to 198 million.”“Those losses are expected to grow to more than $41 billion in 2016, the study said.”

“Last year, Google reported that 56.1 percent of all ads served were not measured viewable by humans.”

“Last December, the Association of National Advertisers and security firm WhiteOps estimated that up to a quarter of video ad views were fraudulent and resulting from software bots. It also said that as much as half of publisher traffic is from bots. This represents a projected $6 billion-plus in wasted ad spend this year.”

“Some industry observers go further than that, arguing that the digital ad industry is beset by traffic and other fraud because there’s a sort of arbitrage going on. Some exchanges, publishers, and ad networks are looking the other way, this argument goes, because they can make money on fraudulent traffic and fake ads.”

“The main losers are the advertisers themselves. But the publishers are getting shafted as well, Spanfeller said, since advertisers are paying $10 per thousand impressions while some publishers ‘get a buck.'”

-Mobile carriers in Europe are hinting that they also may begin to block ads at the carrier level citing increased performance and reduced bandwidth. How soon until we start to see ISPs offer the same services?

-It is estimated that Google is seeing as much as $6B in ad blocking occurring, and their total revenue in 2014 was $66B. That’s no laughing matter for a company making 90% of revenue from ads. Their response was to essentially say that the reason people are blocking ads is because we’re simply not making good enough ads. Yeah…that’s the reason. That type of flippant response to a $6B loss is why you should be very worried, because it means they are worried and don’t yet have an answer.

-For smaller publishers the problem is more pronounced. ProSiebenSat, one of the companies that sued Ad Blocker Plus and lost, stated that ad blocking was costing them upwards of 1/5 of their revenue or €9.2M

-Ad blocking users have grown to an army of nearly 200M people. That’s a word of mouth marketplace that any company would kill to have, except they are evangelizing the death of your business. Think about it as 200M people who have decided what you provide is interesting enough, just not interesting enough to pay for it via your #1 monetization plan. What’s your backup plan for monetization? What that says to me is that there are likely millions of content platforms overvalued and poised to collapse.

-With Apple’s recent announcement that they would allow third party developers to create ad blocking extensions for mobile Safari, the attention brought to this might take it mainstream, considering there are hundreds of millions of iOS devices and mobile Safari represents 25% of browsing. Welcome to the next viral technology success that you can’t actually afford to have take off.

-Facebook’s Instant Articles strategy could possibly be where advertising lives on, meaning that online publishers will have to become even more reliant on the tech giant for revenue, although it is likely both Apple and Google will follow suit. Meaning more of the open web gets sucked into the app environment where walls and AI decide what we will see and hear.

-My own tests with ad blocking has removed every ad from YouTube, one of the primary revenue sources for music labels and artists. Consider that most videos using music on YouTube (likely 60-70%) never generate any ad revenue at all, not to mention that YouTube is still not profitable (really?), this is one basket of eggs I’d be thinking of taking some eggs out of…

-Ad blocking is getting more and more sophisticated with ad block plug ins for Safari, Android, Chrome, and even Spotify. Not only can you block Spotify ads (the freemium model they defend to the death – no freemium no paid), but you can rip tracks from Spotify with all the metadata intact.

–PopcornTime. Free movies and tv shows playing direct to your device with a gorgeous interface, high quality resolution, built-in VPN, and zero ads…need I say more? Expect more solutions like this to pop up, including alternative music platforms. IMAGINE: Playlists created in Spotify exported to a BitTorrent decentralized music player…this will happen.

The next 12-24 months are going to be a watershed where we see just how much of this shakes out. The problems are numerous, but the biggest issue I see is that we’ve spent so much time investing in ad-based technologies and their revenue streams, we’ve not built a single alternative solution which can cover any losses if this all goes belly up. There is a massive consolidation of power occurring at the top of tech where we may only be left with 4-5 companies that control most of the web/Internet as we use to know it, and the creative class is left with no real technology of its own and very few options of how to reach their customers without being at the mercy of another giant tech company.

Years ago I use to drive between California and Oregon quite often and I began to see a trend happening. The boats on the reservoir began to leave the docks as the water receded from the shore. They began to huddle together in the center of the lake as there was less and less water. Essentially they became the last holdouts hoping a great rain would restore everything to the way it was. But it won’t.

Part of the problem California is facing with its shortage of water is due to the fact that they never planned for the possibility of drought, although they certainly talked a lot about it. They are shortsighted. They saw an endless supply of water and all the riches it brought. As humans we very rarely ever prepare for the worst, because we’re always so caught up in the moment and at the moment we’re still feeling the best of times: toilets are still flushing and faucets are still flowing.

The situation with ad revenue and VC backed advances and payments is no different, and if we don’t start working on a fundamental shift on how we as a society pay for things we value, we’re going to see a lot more than just water dry up.

Alan Graham is the co-founder of OCL

You must be logged in to post a comment.