In a world where zero royalties becomes a brag, and one second of music is one second too far.

Let me set the stage: Cannes Lions is the annual eurotrash…to coin a phrase…circular self-congratulatory hype fest at which the biggest brands and ad agencies in the world if not the Solar System spend unreal amounts of money telling each other how wonderful they are. Kind of like HITS Magazine goes to Cannes but with a real budget. And of course the world’s biggest ad platform–guess who–has a major presence there among the bling and yachts of the elites tied up in Yachtville by the Sea. And of course they give each other prizes, and long-time readers know how much we love a good prize, Nyan Cat wise.

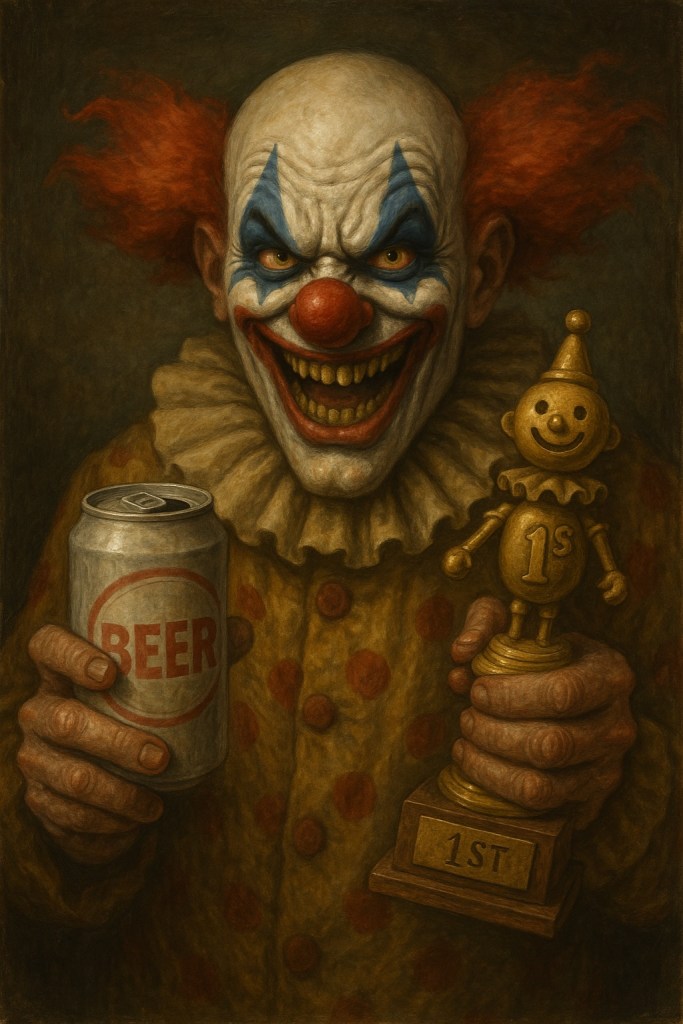

Enter the King of Swill, the mind-numbingly stupid Budweiser marketing department. Or as they say in Cannes, Le roi de la bibine.

Credit where it’s due: British Bud-hater and our friend Chris Cooke at CMU flagged this jaw-dropper from Cannes Lions, where Budweiser took home the Grand Prix for its “One‑Second Ad” campaign—a series of ultra-short TikTok clips that featured the one second of hooks from iconic songs. The gimmick? Tease the audience just long enough to trigger nostalgia, then let the internet do the rest. The beer is offensive enough to any right-thinking Englishman, but the theft? Ooh la la.

Budweiser’s award-winning brag? “Zero ads were skipped. $0 spent on music right$.” Yes, that’s correct–“right$”.

That quote should hang in a museum of creative disinformation.

There’s an old copyright myth known as the “7‑second rule”—the idea that using a short snippet of a song (usually under 7 seconds) doesn’t require a license. It’s pure urban legend. No court has ever upheld such a rule, but it sticks around because music users desperately want it to be true. Budweiser didn’t just flirt with the myth—it took the myth on a date to Short Attention Span Theater, built an ad campaign around it, and walked away with the biggest prize in advertising to the cheers of Googlers everywhere.

When Theft from artists Becomes a Business Model–again

But maybe this kind of stunt shouldn’t come as a surprise. When the richest corporations in commercial history are openly scraping, mimicking, and monetizing millions of copyrighted works to train AI models—without permission and without payment—and so far getting away with it, it sends a signal. A signal that says: “This isn’t theft, it’s innovation.” Yeah, that’s the ticket. Give them a prize.

So of course Budweiser’s corporate brethren start thinking: “Me too.”

As Austin songwriter Guy Forsyth wrote in Long Long Time, “Americans are freedom-loving people, and nothing says freedom like getting away with it.” That lyric, in this context, resonates like a manifesto for scumbags.

The Immorality of Virality

For artists and the musicians and vocalists who created the value that Budweiser is extracting, the campaign’s success is a masterclass in bad precedent. It’s one thing to misunderstand copyright; it’s another to market that misunderstanding as a feature. When global brands publicly celebrate not paying for music–in Cannes, of all places—the very tone-deaf foundation of their ad’s emotional resonance sends a corrosive signal to the entire creative economy. And, frankly, to fans.

Oops!… I Did It Again, bragged Budweiser, proudly skipping royalties like it’s Free Fallin’, hoping no one notices they’re just Smooth Criminals playing Cheap Thrills with other people’s work. It’s not Without Me—it’s without paying anyone—because apparently Money for Nothing is still the vibe, and The Sound of Silence is what they expect from artists they’ve ghosted.

Because make no mistake: even one second of a recording can be legally actionable particularly when the intentional infringing conspiracy gets a freaking award for doing it. That’s not just law—it’s basic respect, which is kind of the same thing. Which makes Budweiser’s campaign less of a legal grey area and more of a cultural red flag with a bunch of zeros. Meaning the ultimate jury award from a real jury, not a Cannes jury.

This is the immorality of virality: weaponizing cultural shorthand to score branding points, while erasing the very artists who make those moments recognizable. When the applause dies down in Yachtville, what’s left is a case study in how to win by stealing — not creating.

You must be logged in to post a comment.