[This is an except from Chris Castle‘s June 7 comment to the Copyright Office regarding the transparency of The MLC. You can read the entire comment here. Although The MLC has launched its “Data Quality Initiative” to great fanfare, that DQI process merely confirms how bad the HFA database is since there still is no MLC database as required by law. Since there’s no indication of when The MLC is going to launch and there is a strong indication that nobody in power is doing anything about it (looking at you, Copyright Office), this is a particularly timely excerpt. Remember you heard it here first if your mechanical royalty statements drop to zero once The MLC takes over on January 1. That is 113 days from today and we have yet to seen a thing from The MLC and we have no promise of when we will see anything. Given that there has been zero investigative journalism on this topic from industry outlets aside from “how does The MLC withstand its own awesomeness” the comments that we are serializing are about all you’re going to get in the way of transparency.]

Quality Control of The MLC’s Operations and Platforms

There is an immediate need for The MLC to demonstrate that its systems actually work. That need will be ongoing, so it would be well for the Office to promulgate regulations requiring a periodic public demonstration of the operability of The MLCs systems, a frequent public disclosure of bugs and bug fixes, and a frequent public disclosure of any missed payments or other glitches. These matters are appropriate for the transparency of The MLC because if either The MLC or another MLC are not required to disclose these items, no one may ever know there was a problem (but see the discussion of whistleblowers below).

In considering the timing, I would caution the Office against thinking in years rather than weeks. There is a tendency to think about these things in annual or more time periods. This will prove to be a mistake given the scale and volume of transactions. Would you tell Visa it only need to confirm the integrity of its fraud detection systems once every three years? Or should it be more frequently? Financial services is a good corollary for streaming mechanicals, with the exception that the royalty payable for each stream starts several decimal places to the right unlike credit card transactions.

There is an immediate need for this transparency. Recall that MLC executive Richard Thompson said at the Copyright Office panel on unclaimed royalties last December, “[A] lot of the time since July has been spent working very closely with the staff at HFA and ConsenSys, really starting to nail down how all of this is going to work at the, you know, lowest operational level, all of the things that we need to work out.” (Referencing the July 8, 2019 designation of The MLC as the MLC.) [1]

Of course, The MLC didn’t announce the selection of HFA and ConsenSys until November 26, 2019[2] and was evidently still interviewing vendors up to that date. Even so, I’m sure The MLC has been hard at work on developing their platform.

Mr. Thompson also stated at the December 2019 panel:

So our current timeline has the first version of the portal going live late Q2, early Q3, of next year [i.e., 2020]. I emphasize again that is the first version. That will not be functionally complete. It will have the, you know, the first set of functionality that we want to make available to the rightsholder community. So in particular, sort of, being able to look at your catalog, manage your catalog.[3]

Late Q2 to early Q3 is now. [As of this post, it is the end of Q3 and we still have nothing but Mr. Thompson still has a job.] To my knowledge, The MLC has made nothing available for songwriters to know what is going on at The MLC or how to start registering works.

Mr. Thompson also stated:

“You know, the first version of the portal doesn’t have statementing on it, because we won’t need statementing until 2021, you know, the first quarter of 2021.”[4]

I would respectfully ask the Office to determine what happens if The MLC is not able to render statements on time. Presumably the income from streaming mechanicals that had been paid by the services directly to songwriters or music publishers would be transferred over to The MLC as of the License Availability Date (currently January 1, 2021). If that transfer occurs and The MLC is not then ready for “statementing” (or, presumably, its corollary, “paymenting”) for the billions if not trillions of streaming transactions for all the world’s music in less than a year’s time from today, then streaming mechanical royalties could drop to zero until The MLC could handle both statementing and paymenting.[5]

While Mr. Thompson seems to be focused on the Q1 2021 distribution date for royalties payable in the normal course, the other significant statementing and paymenting date is July 1, 2021 when the first unmatched distribution is to be paid under Title I. There are also the obvious and expressly stated “public notice of unclaimed royalties” reporting requirements for The MLC’s public facing website listing all unmatched songs (or shares of songs) and publicity efforts for the unmatched.[6] This provision, too, is glitchy, but presumably will come into effect soon. I realize there may be some side deals cut regarding extending that statutory payment date, but it would at least be a confidence building exercise to know that The MLC could make the unmatched payment as of the statutory date if called upon to do so.

Songwriters have very little visibility into The MLC’s operations except what came out at the Copyright Office panels, for which I am grateful, and also various interviews. There is little substantive information in the press, and even less on The MLC’s website. Therefore, it would be very helpful if the Office could require The MLC to demonstrate to the public how its platform is to function. Such a demonstration might bring helpful suggestions from their peers or the ex-US CMOs that have been operating for decades.

It would also be helpful if the Office promulgated a bright line regulation that told songwriters around the world if the July 1, 2021 goal posts have moved and if so where they have been moved to. I must say I have somewhat lost the page on this, given former Register Temple’s last testimony to the House Judiciary Committee about who has agreed what on delaying distribution. This rulemaking would be a great opportunity to tell the world if and how the insiders have decided to change the law.

As the House Judiciary Committee stated:

Testimony provided by Jim Griffin at the June 10, 2014 Committee hearing highlighted the need for more robust metadata to accompany the payment and distribution of music royalties….In an era in which Americans can buy millions of products via an app on their phone based upon the UPC code on the product, the failure of the music industry to develop and maintain a master database has led to significant litigation and underpaid royalties for decades. The Committee believes that this must end so that all artists are paid for their creations and that so-called ‘‘black box’’ revenue is not a drain on the success of the entire industry.[7]

Having accomplished their goal through compulsory legislation, we are all watching the database cadre get to work and looking forward to learning how it is done from their teaching.

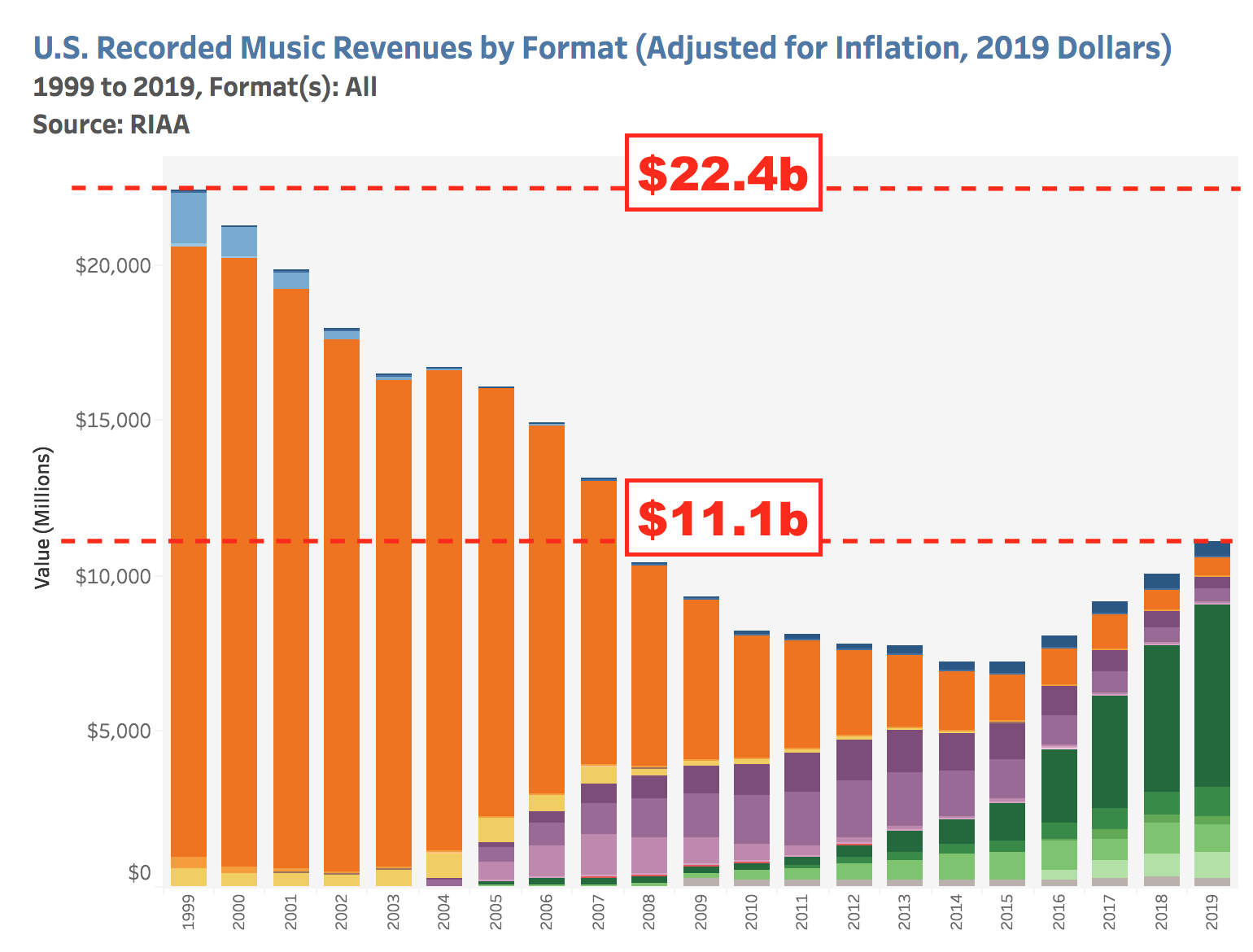

Alternatively, as is widely suspected among some songwriters I have spoken to, The MLC might rely on HFA’s statementing and paymenting functionality to limp along by sending necessary but not sufficient statements to HFA publishers or publishers that HFA can match. This would be, essentially, the same process that got a couple of HFA’s licensing clients sued repeatedly, and ironically led to the Title I safe harbor in the first place.

Absent proper transparency in the runup to the License Availability Date, any sudden drop in revenue would catch songwriters by surprise. In the time of the pandemic, such a sudden contraction of income could be even more devastating than usual.[8]

Transparency would help shine sunlight on that problem. While The MLC may give interviews and appear on panels describing their activities, we should remember the words of the great Bruin John Wooden who cautioned that we should not mistake activity for achievement. If you practice free throws by yourself all weekend, it doesn’t mean you’ll be a better player with the team at Monday practice—or that the team is any more likely to win when it is game time at Pauley on Saturday.

[1] Transcript, United States Copyright Office Unclaimed Royalties Study Kickoff Symposium (Dec. 6, 2019) at 28 ln 15 hereafter “Kickoff Transcript”.

[2] Tatania Cirisano, Mechanical Licensing Collective Selects Leadership, Partners for Copyright Database, Billboard (November 26, 2019).

[3] Kickoff Transcript at 40 ln 2.

[4] Kickoff Transcript at 40-41.

[5] It is well to note that such a contraction probably would not affect direct licenses or HFA’s modified compulsory licenses.

[6] 17 U.S.C. § 115 (d)(3)(J)(iii).

[7] House Report at 8.

[8] Songwriters are already expecting lower royalties in January 2021 according to BMI’s President and CEO Mike O’Neil: “[We] anticipate an impact in January 2021, when today’s performances and corresponding licensing dollars (2nd quarter 2020) will be reflected in your royalty distributions. While you may see a lower distribution that quarter than you might typically receive under ordinary circumstances, given BMI’s business model, we have the time and ability to plan for this outcome.” A Message from Mike O’Neil, BMI.com (April 7, 2020) available at https://www.bmi.com/news/entry/a-message-from-bmi-president-ceo-mike-oneill-regarding-royalty-payments

You must be logged in to post a comment.