Before the

United States Copyright Royalty Judges

Copyright Royalty Board

Library of Congress

Docket No. 21–CRB–0001–PR

(2023–2027)

COMMENTS OF HELIENNE LINDVALL, DAVID LOWERY AND BLAKE MORGAN

Helienne Lindvall, David Lowery and Blake Morgan submit these comments responding to the Copyright Royalty Judges’ notice soliciting comments on whether the Judges should adopt the regulations proposed by the National Music Publishers Association, Nashville Songwriters Association International, Sony Music Entertainment, UMG Recordings, Inc. and Warner Music Group Corp. as the so-called “Subpart B” statutory rates and terms relating to the making and distribution of physical or digital phonorecords of nondramatic musical works that, if adopted by the Judges, would apply to every songwriter in the world whose works are exploited under the U.S. compulsory mechanical license (86 FR 33601).[1]

We object to the proposed rates and terms for the following reasons and respectfully suggest constructive alternatives. The gravamen of our objection is that (1) the Subpart B rates have already been frozen since 2006; (2) no evidence has been publicly produced in the Proceeding that justifies or even explains extending the proposed freeze; (3) very large numbers of songwriters of various domiciles around the world do not even know this proceeding is happening and have not appointed any of the parties to act on their behalf or been asked to consent to the purported settlement; (4) physical sales are still a vital part of songwriter revenue; and (5) there are many just alternatives available to the Judges without applying an unjust settlement to the world’s songwriters.

A. Statement of Interests.

By way of background, following are short summaries of the commenters’ respective biographies demonstrating their respective significant interests in the subject matter of this proceeding.

Helienne Lindvall: Ms. Lindvall is an award-winning professional songwriter, musician and columnist based in London, England. She is Chair of the Songwriter Committee & Board Director, Ivors Academy of Music Creators (formerly British Academy of Songwriters, Composers & Authors BASCA) and chairs the esteemed Ivor Novello Awards. She also is the writer behind the Guardian music industry columns Behind the Music and Plugged In and has contributed to a variety of publications and broadcasts discussing songwriters’ rights, copyright, and other music industry issues.

David Lowery: Mr. Lowery is the founder of the musical groups Cracker and Camper Van Beethoven and a lecturer at the University of Georgia Terry College of Business and is based in Athens, Georgia. He has testified before Congress on the topic of fair use policy[2] and is a frequent commentator on copyright policy and artist rights in a variety of outlets, including his blog at TheTrichordist.com. He has been a class representative in two successful class actions by songwriters against music streaming services.

Blake Morgan: Mr. Morgan is a New York-based artist, songwriter, label owner, music publisher, and the leader of the #IRespectMusic campaign[3] which focuses on supporting fair payment for creators across all mediums and platforms including supporting the American Music Fairness Act sponsored by Representatives Deutch and Issa.[4] Mr. Morgan also lectures on artists’ rights at music, business, and law schools across the United States.

Helienne Lindvall, David Lowery and Blake Morgan (collectively, the “Writers”) are independent songwriters who own the copyrights to many of their songs. They previously were amici in Google v. Oracle[5] together with the Songwriters Guild of America. In some instances, they have written songs whose copyrights they have transferred in limited parts and in some cases for limited periods of time to major music publishers. In other cases, their songs are not owned by major music publishers but are administered by one or more of them, in many cases also for limited periods of time. In some instances, these transfers were in perpetuity subject to certain statutory or contractual termination rights. They also have retained the copyrights to many of their songs and are self-administered songwriters with respect to those nondramatic musical works.

We thank the Copyright Royalty Judges for inviting the public to comment on the proposed regulations in the docket referenced above (“Proceeding”) and the purported “settlement”[6] that in large part resulted in the Copyright Royalty Board’s proposed regulations.

B. Objections, Discussion and Solutions

We appreciate this opportunity to make our views known and hope that our suggestions are helpful to the Judges in trying to solve the frozen mechanicals crisis. We also appreciate that the Judges seek to do justice and find a fair result given their appointed role of administering the awesome power of the government to compel songwriters to accept all rates and terms of the statutory license.

1. Lack of Authority to Negotiate for Non-Participants:

As a threshold matter, we think it is important to clarify the source of authority for the purported settlement as set forth in the Motion. Some play a bit fast and loose with who represents whom in a parade of glittering generalities and hasty generalizations. The Writers are not members of the Nashville Songwriters Association International and have not authorized NSAI to negotiate any agreement on their behalf, nor would the Writers ever authorize any lobby shop to do so.

Neither are the Writers members of the National Music Publishers Association, nor have Writers authorized the NMPA to negotiate any agreement on their behalf. The NMPA has many members but we seriously doubt that the NMPA has expressly obtained authority from any of its members to negotiate the purported settlement on their behalf, outside of its board of directors. That authority may give the NMPA employees cover, but is pretty weak sauce as authority for the negotiation of frozen rates to be applied to all the songwriters in the world.

We doubt that any other songwriter (outside of the insiders) or that any copyright owner gave consent either, aside from members of the NMPA Board of Directors authorizing employees of the NMPA to accept (or perhaps even propose) frozen rates on behalf of the board. Neither do we see any evidence that the NMPA or NSAI were appointed a “common agent” by copyright owners to set prices and otherwise negotiate and agree upon the terms and rates under Subpart B.[7] Therefore, we encourage the Judges to inquire further to determine if an appointment was a necessary condition for settlement or if the majority are claiming a kind of misconstrued authority, perhaps with the best of intentions. One person’s negotiation strategy is another’s catastrophe.

We anticipate that the Judges will take that position that the Writers will be “bound” by the purported “settlement” in the Motion among the NMPA (which owns no copyrights), the NSAI (which owns no copyrights), and the major labels (which in theory own no musical work copyrights). We find it astonishing that entities that do not appear to represent, or to have been appointed a common agent of, all the persons to be bound by the settlement, are still able to use the Copyright Royalty Board to bind nonparties to a settlement. This seems at best contrary to American constitutional jurisprudence requiring the consent of the governed and at worst destructive of the ends of government.

If anyone contests our position that the parties to the settlement had no authority to bind strangers to the deal, let them come forward with a common agent appointment, board minutes, board votes, membership votes, court ruling or other evidence of due process to disclose how this purported settlement described in the Motion was actually approved and which copyright owners authorized the NMPA and NSAI to conclude the agreement on their behalf (and, therefore, which did not).

We think that what such disclosure will demonstrate at most is that the respective boards of directors of the two organizations[8] authorized the settlement. Since neither the organizations nor their respective boards were likely authorized to accept a frozen rate by strangers to that deal, the board members may have merely indicated their own company’s intention to be bound by the settlement. They likely had no actual authority to do more.

Even this seems odd. Each NMPA board member who represents a publisher presumably would be agreeing on their own behalf. It is unclear what the NSAI board actually approved, since NSAI owns no copyrights and at least some of the songwriter board members are likely signed to publishers, perhaps some or all of the same publishers who were voting on the NMPA board.[9] Murkiness abounds. So, if anyone says that their board approval resulted in some kind of “consensus” binding on strangers, that may be something of a misdirection that does not consider the obvious and customary limitations of a board’s authority. We respectfully ask the Judges to get to the bottom of exactly how this happened by asking for supplemental briefs or such other means as the Judges deem appropriate.

The Writers are in two different groups that fairly are not represented in the Proceeding. First, Writers are in the very large and global group of songwriters and copyright owners who cannot afford to participate in the Proceeding. As the Judges are likely aware, yours is very rarified air where only the very rich drive the process but all songwriters must bear the burden of the result. Songwriters and copyright owners living outside the United States (and even those living outside of Washington, DC) are essentially prevented from participating at hearings in a far-away capitol although the Judges’ rulings directly affect their works when exploited in America. This is how process becomes punishment.[10]

Second, the Writers are in another bucket with some songs still co-published or administered by publishers that may be represented by the NMPA in the settlement—we do not know because individual publishers did not sign the Motion in their own names. None of those publishers have consulted with the Writers about freezing the statutory royalty rates for yet another five years and essentially granting a reduced rate license without our permission. Many co-publishing or administration agreements include a restriction on the publisher that prohibits them from granting licenses at less than the statutory rates—songwriters did not consider negotiating an additional restriction that would prohibit the publisher from lobbying to indirectly reduce the rate through freezing the statutory rate and then bootstrapping that agreement to apply to the world through the CRB. Perhaps the CRB will give songwriters a reason to start negotiating a “no frozen rate lobbying” marketing restriction in future deals.

Respectfully, the Judges should not enable these publishers to do indirectly that which they cannot do directly. We would ask the Judges to inquire further and opine as to whether such marketing restrictions are at work in the purported settlement as to songwriters or publishers administered by any of the settling publishers. Since those publishers are not individually parties to the settlement, we have no way of confirming who is in and who is not.

Regardless, Writers did not authorize anyone to negotiate the frozen rates on their behalf and never would. If the Judges adopt the proposed settlement without a mechanism to obtain consent of those they govern, such a ruling seems to us to fly in the face of all the fundamental building blocks of democracy and in particular American Constitutional democracy. Accordingly, Writers reserve the right to challenge any such decision to freeze mechanicals on a number of grounds[11] including due process, equal protection and 5th Amendment takings.

The parties to the purported settlement would have the Judges believe that because they claim that ‘‘the settlement represents the consensus of buyers and sellers representing the vast majority of the market for ‘mechanical’ rights for Subpart B Configurations”[12] and seem to ask the CRB to accept without question the lack of evidence of the authority to negotiate the settlement in the first place which belies the unelected “consensus.” It must be said that on the one hand, songwriters are not polled to determine what they want in the way of rates, but on the other hand their number or the number of their works are used to justify frozen rates to argue for a “majority” view (when songwriters were never asked if they want the freeze). Such “consensus” is chimerical and is, frankly, an equivocation that defies a common definition[13] of the word “consensus” that we find inapt given the current facts and is closer to Kings X.

The settling parties (presumably the NMPA in this case) would have the Judges apply their private deal to all songwriters throughout the world. It’s easy to get a faux consensus from “the majority” if you do not invite—and even attack or threaten[14]–those with opposing views. It illustrates the “tyranny of the majority” that every American high school civics class discusses in the context of governance[15]–even assuming there was a vote of the affected songwriters which there apparently was not.[16]

Therefore, from the outset the proposed rule is simply not a reasonable basis for setting statutory rates or terms for those not party to the voluntary agreement set forth in the Motion.

But on a more practical note, we think songwriters will ask what can be done to try to fix the mess the parties have created? We offer several concrete solutions.

2. Limit the Settlement to Named Parties to the Agreement or Let Sunlight Shine on the Settlement if Settlement Applies to All Songwriters in the World:

We call the Judges’ attention to the record company parties to the settlement. Note that each of the major labels signed in their own organization names, yet for some reason the publishers did not. Had they signed in their own names, the symmetry between the two might be obvious due to common ownership at the group level.[17]

The Judges could require that the voluntary settlement apply only to those parties who actually agreed it, rather than trade associations that own no copyrights and likely have limited agency at best. The Judges could cabin the rates and terms to those parties who are actually signatories to the settlement, directly or indirectly. The publishers involved could be ordered to step forward for the rationally related purpose of determining who the settlement rate should apply to. This approach would treat the purported settlement more in the nature of a voluntary license among the parties as is permitted under the Copyright Act. This cabined approach seems to be consistent with the Act and the proper role of regulatory agencies like the CRB, not to mention the Constitution.

If the Judges do not wish to take this approach, the Judges may wish to assure that all songwriters who are affected by their ruling are provided with the full picture of what the deal was that induced the purported settlement. This approach recognizes that the proposed regulations do nothing to disclose all consideration that was paid in connection with the settlement. This question has been raised by many interested persons, including Representative Lloyd Doggett in a July 13, 2021 letter[18] to the Librarian of Congress and the Register of Copyrights regarding CRB procedures.

The settlement expressly refers to undisclosed terms that sound very much like other consideration exchanged and also expressly refers[19] to a side deal or “MOU” between the NMPA and the major labels.[20] How can the Judges determine, or expect anyone outside the insider group to agree, that the rates and terms set forth in the proposed regulations are fair and reasonable without knowing the full extent of the consideration exchanged? Therefore, the proposed rule as drafted is simply not a reasonable basis for setting statutory terms or rates for those not party to the voluntary agreement as set forth in the Motion and who are not “in the know” regarding its terms including the terms of the MOU.

3. Opt In for Independents and Co-Published Songwriters:

We perceive the obvious lack of authority to bind non-parties is a fatal flaw of the proposed settlement. If true, lack of authority is likely sufficient good cause for the Judges to reject the settlement without even addressing whether the rates and terms meet the willing buyer-willing seller standard required by Congress.

We recognize that the Judges may wish to avoid an outright rejection of the purported settlement. An agreement among the parties is consistent with the goals of a voluntary negotiation. One remedy might be for the Judges to require the parties to construct an opt-in structure that would only apply to those who affirmatively agree to accept the frozen rate. There clearly are precedents for implementing an opt-in structure that would allow songwriters and copyright owners to accept the settlement or reject it and negotiate their own arms-length rate as true and unrelated willing sellers to a willing buyer.[21] If there really is a “consensus,” an opt-in process would simply confirm it in a legally cognizable manner.

For example, if copyright owner A was party to a co-publishing agreement with publisher X who is represented on the NMPA board, it would be a simple thing to require publisher X to proffer an authorization document permitting the negotiation of the settlement on behalf of copyright owner A. Failing that proffer, publisher X could put the settlement out for opt-in consent by copyright owner A and those in the same class as copyright owner A. An opt-in process seems efficient. Common questions would predominate, the publishers concerned would not be prohibitively numerous, the copyright owners could easily be located based on the billing relationship between them and publisher X and an opt-in structure would no doubt be preferable and less costly than other remedies.

Alternatively, songwriters or copyright owners could be allowed to opt-out of the settlement by a simple notice by their publisher to them requesting an opt-in, or from them to their publisher opting in or out. The Judges would, of course, do well to specify the rules for this process and supervise the administration.

Absent this or similar evidence of authority, there will always be an open question of whether the purported settlement provides a reasonable basis for setting statutory terms or rates which may be answered later down the line in the CRB or other fora.

4. When the Willing Buyer and Willing Seller Are Effectively the Same Legal Person:

It must be said that we sympathize with the position that the Judges are in of trying to divine a free market rate in America where songwriters have not been free in over 100 years. In fact, songwriters in America have not been free for so long we could safely say they have never been free in stark contrast to the U.S. economy generally. Generations of songwriters are held guilty of some long-forgotten and Kafka-esque original sin requiring a degree of government regulation as though songs were hazardous materials. Regulation that protects monopolists like Google and iHeartMedia from the supposed anticompetitive urges of songwriters who we are asked to believe seek out the closed door of the writer room for one reason–collusion.

While this willing buyer-willing seller standard makes good sense in the case of webcasting rates[22] or streaming mechanicals where the parties typically are not and are not likely to be related, it is extraordinarily difficult for the Writers to swallow in the case of the parties to the purported settlement—an ancient conflict of interest that was easily predictable on the face of the “Music Modernization Act.”[23] There is nothing modern about this unitary buyer/seller problem.

The major publishers are, of course, owned at the group level by the same companies that own the major labels. That’s what makes them “major” but that is also what makes them unitary. Assuming arguendo that the major publishers have obtained the consent of their co-publishers or their administration principals, they would be free to enter into any permitted settlement even with their affiliated record company music users. But the Motion is hardly a willing buyer-willing seller scenario—the two are essentially the same legal person, or are “unitary.” Congressman Doggett raised a question about this very issue in his Letter, and we raise it here to the CRB. We think it deserves a detailed reply from the CRB and will be a key legal precedent going forward under the “new” MMA standard.[24] All the more reason why the settlement is more suited to a voluntary license among the parties than a rule that applies to all the world.

The Judges may find the recent report[25] by the UK Parliament’s Digital Culture Media and Sport Committee to be helpful on this point; Ms. Lindvall and the Ivors Academy campaigned for the DCMS Committee’s inquiry.

The DCMS Committee called upon the Government to have the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority investigate competition in the recorded music market, particularly the tied song and sound recording markets,[26] noting that:

“With [independent] music publishers…unanimously calling for the value of the song to have parity with the value of the recording [citation omitted], it is conspicuous that the MPA [the UK counterpart to the NMPA] refused to give a definitive perspective on the debate, particularly given that the publishing arms of the three major music groups are counted amongst their members….Whilst the major music groups dominate music publishing, there is little incentive for their music publishing interests to redress the devaluation of the song relative to the recording.”[27]

Accordingly, we do not believe, as discussed more fully below, that the purported settlement agreement in any way approximates fair or reasonable royalty rates and terms, or rates and terms that would have been negotiated in the marketplace between an arms-length willing buyer and a willing seller, i.e., a non-unitary buyer/seller. Given the position expressed by the DCMS Committee, it’s entirely possible that at least the UK Parliament may wish to resolve the issue in another forum.

We are open to being persuaded otherwise by the Judges, but it appears that the unitary willing buyer-willing seller will establish a critical precedent going forward. Therefore, the proposed rule is simply not a reasonable basis in this great moment for setting statutory terms or rates until the application of this standard to related parties is clearly spelled out by the CRB and reviewed.

5. Vinyl Is a Booming Business:

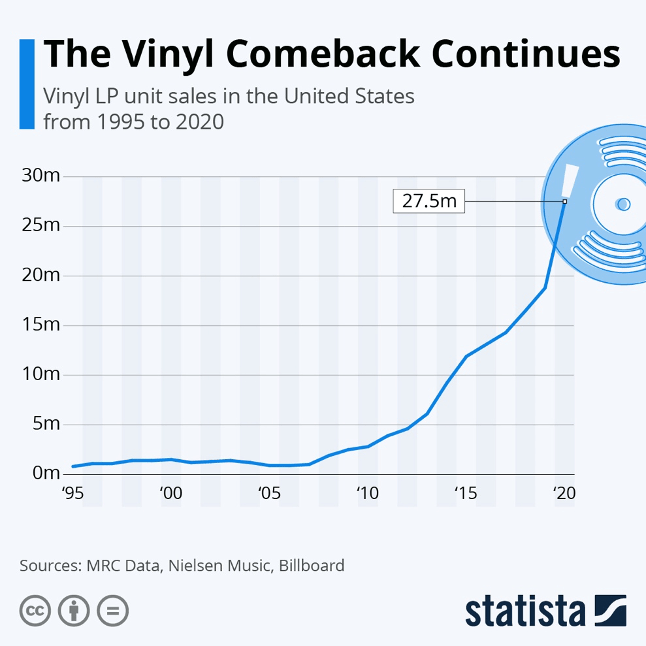

We ask that the Judges take notice of the multitude of news reports on vinyl sales.[28] Contrary to the vague assertions by NSAI members outside of the Proceeding about unnamed and undisclosed “industry revenue analysis” when defending their decision to “accept” a frozen rate because they believe that physical is a declining configuration,[29] vinyl sales are, if anything, understated due to the severe inability of supply to keep up with demand. (Why a rational commercial actor would allow that mismatch to continue to such an egregious extent and to the detriment of artists and songwriters is a whole other question.[30])

These supply chain problems started well before the pandemic,[31] so please do not allow yourselves to be “gaslighted” into the belief that the problems are caused by the pandemic. Since the whole point of capitalism is for supply to meet demand, we must assume that this situation will be remedied eventually considering the incredibly strong and nearly vertical demand for vinyl, yet that remedy is slow in coming.

While the 2008 coming of Spotify is taken by the press (and Spotify itself) as some sort of celestial arrival of a savior straight out of the Book of Revelation,[32] the data tell a different story about vinyl sales. For whatever reason of consumer taste, the coming of Spotify was also roughly the beginning of the vinyl boom. Respectfully, it does not take an economist to read the newspaper—stories of vinyl’s resilience to cannibalization by streaming abound.

This upward sales trend is reflected in new survey data as well. According to a small survey conducted by Artist Rights Watch[33] of self-selected songwriters during the period June-July 2021, approximately 26% of respondents said that, roughly speaking, their songwriting income from physical sales had increased over the last two years, and 32% said they expect their income from physical sales to increase over the next two years.[34]

These survey results are consistent with the views expressed by Jeff Gold[35], a music industry veteran, historian and author who has operated the Record Mecca collectibles site for many years. Rolling Stone profiled Mr. Gold as one of the five “top collectors of high-end music memorabilia.” Mr. Gold told us in an interview[36]:

“I think the vinyl boom is being driven by a number of factors. First, nostalgia: people like me love the experience of looking at an album cover, putting a vinyl record on the turntable, and traveling back in time. The Record Collector world I live in has expanded as well, with highly collectible records [selling] for much more than ever.

Second, for younger people I think there is a collectible factor – – they are trying something from a different era, it’s trendy to have a turntable and play vinyl records, and they think maybe this is something they can buy that’ll be worth more later. And that is often the case.

Also, there’s the Record Store Day[37] phenomenon, under pressing records to make instant collectibles. And to some [vinyl records] are merch[andise] for fans of artists who want to own everything connected to that act.

The market for vinyl has dramatically expanded, and the rare vinyl I sell is more desirable than ever. If I had to guess I would think that the collectible record world will continue to expand, but at some point the fad vinyl buying will begin to ebb. Though I’ve been saying that for a long time and there’s no sign of it.”

The Artist Rights Watch small survey and recent commentary[38] supports a phenomenon that we respectfully suggest the Judges should explore further before accepting the alleged “consensus” for the purported settlement as fact—a significant number of songwriters appear to find mechanical royalty income from physical sales to be important to them and likely would not accept the terms of the voluntary agreement. Again, we are not trying to dictate rates and terms to those who find the voluntary agreement to suit their needs; they should have their rates and terms. But we respectfully ask the Judges not to impose those frozen rates on everyone else without their participation and consent as well as evidence. What is good for the goose may be anathema to the gander.

Even if every single one of the current vinyl trends are wrong, even if vinyl stops being a resurgent business and abruptly crashes and burns at some point in the next five years due to supply chain problems or reversals in consumption patterns not currently measurable, even if the NSAI songwriters’ undisclosed sources turn out to be 100% correct, what remains even in the industry-wide and world-wide 1% of revenue projected by the NSAI songwriters is still a significant revenue stream to a large portion of songwriters[39] and even music users. We will believe the users do not care about physical and digital downloads when the first record company president comes forward and declines 15% of annual billing.

These assertions and speculations about the future are a fine example of a judgement based on conditional probabilities that does not consider the effect of prior probabilities. If this sudden crash theory really is part of the majority’s thinking, it does seem that the least they could do is provide the Judges and the public with supporting evidence on the record for their projection (or their guesswork) that so far is entirely absent from the record.

We do not make an emotional appeal, however. Sales levels do not change the fact that songs have value that deserves greater economic analysis and justification than a finger in the wind. As the DCMS Committee observed in their referral to the UK’s competition authorities, there are some unusual forces at work here. The Motion may well provide greater evidence for such a review albeit inadvertently.

In the absence of an economic case put on by any party to the voluntary agreement regarding freezing Subpart B rates, we ask that the Judges take notice of the overwhelming amount of public information available to document the importance of vinyl and the error of the fundamental assumptions of the NSAI songwriters which we assume gave voice to certain NMPA members. We have provided the Judges with a handful of representative articles above.

While the CRB may have other reasons for continuing to impose the existing frozen mechanical rate on the world’s songwriters for another five years, relying on an unnamed “industry revenue analysis” of imaginary dwindling physical sales without inquiring further when there is ample public evidence to the contrary seems to be an unreasonable and arbitrary basis for setting statutory terms or rates. In fact, putting your finger in the air and guessing that vinyl sales will reverse course into a nose-dive in the face of overwhelming facts and data to the contrary seems the very definition of arbitrary.

6. Disclosure Should be Mandatory:

Respectfully, we believe there is a compelling need for the Judges to require the disclosure of both the settlement agreement that established the frozen rates as well as the MOU referenced in the Motion.[40] It appears from the Motion that there was additional consideration beyond putting a finger in the air and deciding to freeze the rates another five years; yet, that additional consideration is described but not disclosed. It seems that no copyright owner (other than insiders) can rationally evaluate the purported settlement without knowing all the facts.

We respectfully call the Judges’ attention to analogous facts in Pandora’s ASCAP and BMI rate court proceedings from 2007. While dated, the story is good background for understanding the problems that can be unleashed from bootstrapping secret deals into law—in the Pandora case, one could say that it led directly to the Music Modernization Act’s provisions requiring random assignment of rate court judges. This quote from Billboard[41] is a succinct description of the problem:

Back in 2007-2010, when ASCAP and BMI rate court judges were involved in litigation between DMX and performance rights societies, the judges examined the direct licensing deals DMX cut with publishers. During that process, judges did not review the advances or any of the other aspects of the deal, and only looked at the reduced per-store royalty rate. Consequently, in the case of BMI, this resulted in the per-store negotiated rate falling from $36.36 to a per-location fee of $18.91, much to the chagrin of the publishers, who stayed a part of the PROs’ blanket licenses. The ASCAP rate court returned a similar finding.

Congressman Doggett also correctly raised this question in his Letter and it is entirely understandable—without disclosure of all consideration, strangers to the settlement are being asked to buy a pig in a poke.

Accordingly, we ask that you compel the disclosure of all documents, payments and other consideration that changed hands or were promised to change hands in the purported settlement. This would include any payments outside the four corners of the Motion but related to the purported settlement. In the absence of that disclosure or binding certification that it does not exist, the proposed rule is simply not a reasonable basis for setting statutory terms or rates until the full terms of the purported settlement are disclosed or the settlement is cabined as a voluntary license among the parties.

7. Raising the Rates:

First and foremost, the problem with the CRB adopting the purported settlement as the law of the land is the appearance of the bootstrapping of a private deal among apparently related parties and the controlled opposition into rates and terms that apply to all songwriters in the world. As Congressman Doggett says in his Letter, these are rates and terms that apply to all songs ever written or that ever may be written. We know you will agree that the rule making authority of the CRB is a serious and solemn example of the awesome power of the government over unrepresented songwriters.

The potential for this bootstrapping is particularly offensive to songwriters who live outside the United States as evidenced by opposition to the frozen mechanicals from a host of international songwriter groups.

We wish to express our desire for a separate and higher rate from the frozen rate accepted by the parties to the purported settlement. We recognize the corner that the CRB has been backed into regarding raising the rates that have been frozen for so long that they have been substantially eroded by inflation without even considering the value of songs to the booming vinyl business. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics CPI-U calculator[42] (the same index used by the Judges in the recent Web V rate determination), a 9.1¢ rate set in 2006 would be indexed to 12¢ today. We therefore estimate that 9.1¢ in 2006 would have the buying power today of approximately 6¢, less than the 1992 mechanical rate established 29 years ago.[43]

However justified, we are sure that raising the 9.1¢ rate across the board would be met by a great howling and rending of garments by at least some of the parties to the purported settlement. The easy answer to this issue is one raised by Congressman Doggett in his Letter–limiting the settlement rate to the settling parties and setting a higher rate for non-settling parties, i.e., the inverse of the trick referenced above that was played by DMX on the entire industry and the rate courts.

The new minimum statutory rate applied to the non-settling parties could be as simple as a headline rate between a bounded range greater than 9.1¢ and up to 12¢ with the appropriate adjustment for the long-song formula. That headline rate could then be adjusted for inflation and indexed to the CPI-U for the out-years in a similar manner as the Judges applied in Web V. Even these rates are excruciatingly low and demonstrate the deep hole that the government imposed on songwriters between 1909 and 1978 when the rate for generations of songwriters was frozen at 2¢ through two World Wars, the Great Depression, a global pandemic, two post-war booms and a moon walk. Songwriters have been digging out ever since, both in the US and abroad due to America’s long commercial shadow. The Writers fear that a similar freeze has developed with the Subpart B rates and without meaningful consultation.[44] While we cannot reasonably ask the CRB to solve all the world’s mistakes, we can ask that the Judges not repeat them. As Congressman Doggett says, we are concerned that we not misstep.

Alternatively, the CRB could, after consultation with representative parties opposing the frozen rates such as the Songwriters Guild of America, Ivors Academy, ATX Musicians, the Society of Composers and Lyricists, MusicAnswers, the Screen Composers Guild of Canada, Alliance of Latin American Composers & Authors, Asia-Pacific Music Creators Alliance, Pan-African Composers and Songwriters Alliance, Music Creators North America, the Alliance for Women Film Composers and ECSA appoint a representative for independent songwriters to negotiate with both the major labels and the independent labels on rates applicable to and higher than the rates in the settlement. Such a consultation in this or another forum would go a long way toward clearing up the due process and equal protection Constitutional issues hanging like a cloud over the current Proceeding. Obviously, the cost of such negotiation should not be borne by the songwriters or recouped from their royalties.

Therefore, absent such a ruling by the Judges, the proposed rule is simply not a fair or reasonable basis for setting statutory terms or rates until there are truly representative bodies negotiating on behalf of songwriters and independent copyright owners.

Thank you again for this opportunity to express our views on the proposed rule. We respectfully hope that our comment has provided the Judges with some additional insight into how the proposed rule affects independent songwriters and publishers both in America and around the world, particularly since none of us can afford to participate in the rate setting proceeding itself. We greatly appreciate the Judges’ willingness to avoid process becoming punishment.

Respectfully submitted.

Christian L. Castle

Christian L. Castle, Attorneys

9600 Great Hills Trail, Suite 150W

Austin, Texas 78759

July 26, 2021

[1] We focus in this comment almost entirely on the Subpart B rates applicable to physical carriers under 37 C.F.R. §385.11(a). We note, however, that there is some apprehension among songwriters that the “music bundle” rate in 37 C.F.R. § 385.11(c) could be twisted in a way to drag Non-Fungible Tokens into the frozen rates. We doubt that Congress intended to include NFTs in the statutory rates since they did not exist even at the time of the Title I amendment to Section 115. It would certainly add insult to injury for large sums to change hands for NFTs but songwriters be reduced to their usual meagre gruel in compensation while everyone else enriches themselves from the songs. Clarity on this point would be appreciated.

[2] See The Scope of Fair Use: Hearing before the Subcomm. on the Courts, Intellectual Property and the Internet of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 113th Cong. (Jan. 28, 2014) (statement of David Lowery)

[3] See #IRespectMusic campaign, available at https://www.irespectmusic.org.

[4] See Reps. Issa, Deutch Introduce Bill to Ensure Artists Receive Fair Pay for FM/AM Radio Airplay (June 21, 2021) available at https://issa.house.gov/media/press-releases/reps-issa-deutch-introduce-bill-ensure-artists-receive-fair-pay-fmam-radio.

[5] Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc., 593 U.S. ___ (2021), Brief of Amici Curiae Helienne Lindvall, David Lowery, Blake Morgan and the Songwriters Guild of America in support of Respondent (2021) available at https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/18/18-956/133298/20200218155210566_18-956%20bsac%20Helienne%20Lindvall%20et%20al–PDFA.pdf.

[6] Motion To Adopt Settlement Of Statutory Royalty Rates and Terms For Subpart B Configurations, Docket No. 21-CRB-0001-PR (2023-2027) hereafter the “Motion.”

[7] See, e.g., 17 U.S.C. §115(c)(1)(D).

[8] We invite the Judges to take notice of the relationships at the board level between the NMPA and the NSAI which is beyond the scope of the comment, but we think the Judges may find very relevant for discussions of negotiating authority and the scope of designation of a common agent.

[9] It must be noted that the NMPA board and the NSAI board share members from time to time.

[10] We are mindful of the result of the WTO arbitration over the Fairness in Music Licensing Act that found the United States liable for damages in violating the TRIPS Agreement. See WT/DS160/12 (Jan. 15, 2001) available at https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S006.aspx?Query=(@Symbol=%20wt/ds160/*)%20and%20(@Title=%20((arbitration%20under%20article%2021.3)%20and%20((award%20of%20the%20arbitrator)%20or%20(report%20of%20the%20arbitrator))))&Language=ENGLISH&Context=FomerScriptedSearch&languageUIChanged=true#,

[11] See, e.g., United States v. Arthrex, Inc., 594 U.S. ____ (2021).

[12] Motion at 4.

[13] The Cambridge English Dictionary defines “consensus” as either a “generally accepted opinion” or a “wide agreement,” neither of which apply to frozen mechanicals.

[14] Paul Resnikoff, AMLC Board Member Accuses NMPA President David Israelite of Tortious Business Interference and Collusion, Digital Music News (Nov. 28, 2018) available at https://www.digitalmusicnews.com/2018/11/28/amlc-nmpa-president-david-israelite-collusion/

[15] Thomas Jefferson, First Inaugural Address (1801) (“All too will bear in mind this sacred principle, that though the will of the majority is in all cases to prevail, that will, to be rightful, must be reasonable; that the minority possess their equal rights, which equal laws must protect, and to violate would be oppression.”)(emphasis added); James Madison, Federalist Papers 10 and 51. John Locke, Second Treatise of Government (1689) at par. 95 (“[N]o one can be put out of [his property], and subjected to the political power of another, without his own consent.”)

[16] The tradition of concern with the familiar “tyranny of the majority” sounds in discussions of representative government, the concern being that the majority that gives a representative quorum in a body also could lead to disastrous consequences for the minority. This is particularly true when the governed have rules imposed on them that they had no part in crafting by persons they had no part in electing. Washington expressed it well and highlights the very point before this Court today: “To be fearful of vesting Congress, constituted as that body is, with ample authorities for national purposes, appears to me the very climax of popular absurdity and madness. Could Congress exert them for the detriment of the public without injuring themselves in an equal or greater proportion? Are not their interests inseparably connected with those of their constituents? By the rotation of appointment must they not mingle frequently with the mass of citizens? Is it not rather to be apprehended, if they were possessed of the power before described, that the individual members would be induced to use them, on many occasions, very timidly and inefficaciously for fear of losing their popularity and future election?” George Washington, “To John Jay,” August 15, 1786, The Papers of George Washington, “Confederation Series,” Vol. 4 (1976) at 212–13 (emphasis added). If the truth is as we apprehend it, that a dedicated group of essentially unelected likeminded people known for extracting vengeance from anyone who dares question them got in a private room at a private meeting and decided the fate of the world’s songwriters was their unelected remit, then this is not even a vote fulfilling the tyranny of the majority because there was no vote and there was no majority—just tyranny. de Tocqueville admonishes that “[t]he despotism of faction is not less to be dreaded than the despotism of an individual.” Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Vol. 2, Ch. XIV (1840) at 289.

[17] This is particularly relevant in the case of a songwriter who has entered one of the various publishing, co-publishing or administration agreements commonly in use in the music business. If publisher X intends to be bound by the settlement, yet does not act under its own name in the settlement, songwriters “signed” to publisher X have no way of knowing if they are to be bound. While certain relationships can be inferred, it seems that there should be clarity regarding the parties to such a watershed agreement.

[18] Letter from Hon. Lloyd Doggett to Librarian of Congress Dr. Carla Hayden and Register of Copyrights Shira Perlmutter (July 13, 2021), available at https://thetrichordist.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/letter-library-of-congress-register-of-copyrights-7.13.21.pdf hereafter “Letter”.

[19] “Concurrent with the settlement, the Joint Record Company Participants and NMPA have separately entered into a memorandum of understanding addressing certain negotiated licensing processes and late fee waivers.” Motion at 3.

[20] The “MOU” description and “late fee waiver” reference brings to mind another late fee “MOU” being the NMPA Late Fee Program available at http://www.nmpalatefeesettlement.com/mou2/index.php. If this MOU is a version of that MOU, it could be a substantial sum. (“The Record Companies have represented there is approximately $275 million in “pending and unmatched” accrued royalties (the “P&U Royalties”) that have not been distributed to the music publishers. In exchange for waivers of certain late fees through 2012, the Record Companies must comply with the provisions of the MOU, including paying participating music publishers and foreign societies their respective market share of accrued P&U Royalties.” Available at http://www.nmpalatefeesettlement.com/group_1/summary.pdf)

[21] For example, see the Songclaims.com portal used to implement the Spotify class action settlement.

[22] 17 U.S.C. §§ 112, 114(d)(2).

[23] 17 U.S.C. §§ 115(b)(1) and (3).

[24] It is worth noting that we have been unable to find any reference to the unitary buyer/seller in any of the public comments or legislative history regarding the Music Modernization Act. In fact, the NMPA’s “pitch sheet” entitled Music Modernization Act (MMA): Bringing Songwriters into the Digital Age (Dec. 28, 2017) states that the new MMA rate standard establishes “[r]ates based on what a willing buyer and a willing seller would agree to reflect market negotiations” in contrast to the 801(b) standard that resulted in “below-market rates.”

[25] Digital Culture Media and Sport Committee, Economics of Music Streaming (Second Report of Session 2021-22), UK Parliament (July 15, 2021) available at https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/6739/documents/71977/default/.

[26] Id. at 3 and 105.

[27] Id. at 71 (emphasis added).

[28] Tina Benitez-Eves, Vinyl Record Sales up 108.2% in First Half of 2021, American Songwriter (July 16, 2021) (“For the past 15 years, vinyl record sales have seen consecutive growth, despite the continued uptick of digital consumption in the U.S. and drop in sales and backup in production due to the pandemic.”) available at https://americansongwriter.com/vinyl-record-sales-up-108-2-in-first-half-of-2021/; Sarah Whitten, Music Fans Pushed Sales of Vinyl Albums Higher, Outpacing CDs, Even As Pandemic Sidelined Stadium Tours, CNBC (July 14, 2021) (“Music consumption in the first half of the year has remained robust even without the sold-out stadium tours, according to a new report. While on-demand audio streaming is up 15%, consumers are also looking to own more tangible collectibles like vinyl albums, which continue to surpass CD sales. In the first six months of 2021, 19.2 million vinyl albums were sold, outpacing CD volume of 18.9 million, according to MRC Data, an analytics firm that specializes in collecting data from the entertainment and music industries.”) available at https://www.msn.com/en-us/entertainment/news/music-fans-pushed-sales-of-vinyl-albums-higher-outpacing-cds-even-as-pandemic-sidelined-stadium-tours/ar-AAM6S31; Ed Christman, Audio Streams Up 15%, Vinyl Sales Double in First Half of 2021, Billboard (July 15, 2021) (“Vinyl sales, which have grown for the past decade, more than doubled between January and June, up 108.2% to 19.2 million from 9.2 million in the first six months of last year. Even CD sales, which have been steadily and precipitously declining, posted a modest 2.2% gain, to 18.9 million units. The only serious loss was in digital sales: Album downloads fell 26.8%, to 12.92 million, while track sales dropped 20.3%, to 101.8 million. But physical sales rose so much that, for the first time in years, total album sales rose, by 12.6% to 51.26 million.”) available at https://www.msn.com/en-us/music/news/audio-streams-up-15-vinyl-sales-double-in-first-half-of-2021/ar-AAM9Sk7); Sam Willings, Sainsbury’s Supermarket Will Stop Selling CDs, Sale of Vinyl Records Will Continue (July 13, 2021) (“A spokesperson for the British Phonographic Industry (BPI) told the BBC that “The CD has proved exceptionally successful for nearly 40 years and remains a format of choice for many music fans who value sound quality, convenience and collectability.” They continued: “Although demand has been following a long-term trend as consumers increasingly transition to streaming, resilient demand is likely to continue for many years, enhanced by special editions and other collectable releases.”) available at https://www.musictech.net/news/sainsburys-supermarket-will-stop-selling-cds-sale-of-vinyl-records-to-continue/; Andre Paine, Record Store Day set to deliver another summer boost for vinyl sales, Music Week (July 15, 2021)(“ Participating shops will be expecting queues from the early hours as fans and record collectors seek out rare and exclusive vinyl titles being released especially for the day.”) available at https://www.musicweek.com/labels/read/record-store-day-set-to-deliver-another-summer-boost-for-vinyl-sales/083710; Sage Anderson, Barnes & Noble ‘Vinyl Weekend’ Launches With Grateful Dead, Fleetwood Mac Exclusives, Rolling Stone (July 15, 2021)(“Barnes & Noble may be known for their cozy bookstores and massive collective of great reads across all genres, but the retailer has also just announced the return of their fan-favorite “Vinyl Weekend,” which offers dozens of limited-edition records and exclusive in-store and online specials.”) available at https://www.rollingstone.com/product-recommendations/lifestyle/barnes-and-noble-vinyl-turntable-sale-1197904/.

[29] L.B. Cantrell, NSAI Songwriters Respond to Criticism of Decision not to Challenge Physical Mechanical Rates, Music Row (June 2, 2021)(“Based on industry revenue analysis, it is anticipated that physical mechanical royalties will amount to less than 1% of the total mechanical royalty revenue in the United States during 2023-2028, the rate period this CRB proceeding covers.”) available at https://musicrow.com/2021/06/nsai-songwriters-respond-to-criticism-of-decision-not-to-challenge-physical-royalty-rates/.

[30] Erin Osman, “It’s a Total Nightmare”: Problems at Direct Shot Distributing Has Made New Vinyl and CDs Scarce, Billboard (Dec. 18, 2019) (“Since April, record stores and labels have been plagued by a distribution bottleneck that began when Warner Music Group moved its physical product to Direct Shot Distributing (DSD). The change made DSD, which also has contracts with Universal and Sony, one of the largest distributors of physical music in the country. The problem became apparent on April 13 — Record Store Day, the busiest and most profitable day of the year for many retailers — when some stores didn’t receive the exclusive releases they had ordered. Since then, the problem has gotten worse.”), available at https://www.billboard.com/articles/business/8546794/direct-shot-distributing-problems-vinyl-cds-physical-product.

[31] Allison Hussey, A Major Music Distributor Has Stifled Vinyl Sales for Record Stores and Indie Distributors, Sources Say, Pitchfork (Dec. 19, 2019) available at https://pitchfork.com/thepitch/a-major-music-distributor-has-stifled-vinyl-sales-for-record-stores-and-indie-labels-sources-say/.

[32] David Rowan, Daniel Ek: Europe’s Greatest Digital Influencer Tops Wired 100, Wired (May 16, 2014) available at https://www.wired.co.uk/article/wired-100-daniel-ek.

[33] “Thriving on scorn from the establishment since 2015”, http://www.artistrightswatch.com

[34] Artist Rights Watch, Songwriter Mechanical Royalty Income Questionnaire June-July 2021 to be made available at http://www.artistrightswatch.com and results available from the commenters (N=54).

[35] https://recordmecca.com/about/

[36] Available from the authors.

[37] See, e.g., https://recordstoreday.com

[38] See, e.g., Artist Rights Watch Podcast Episode 1 “Frozen Mechanicals” available at https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-artist-rights-watch/id1574250584; The Trichordist.com “frozen mechanicals” category https://thetrichordist.com/category/frozen-mechanicals/

[39] We are likewise unaware of any provision of the Copyright Act or regulations promulgated there under that provides for a sales-based determination of any particular rate. Such an argument appears to be exactly what underlies the NMPA and NSAI acquiescence to frozen rates but it simply is not the law that the fewer phonorecords sold the lower the royalty rate that the CRB may set.

[40] There may be other side agreements that are not disclosed in the Motion.

[41] Ed Christman, Less Could Be More: Why Merlin’s Deal with Pandora May Pay Off, Billboard (Dec. 11, 2014) (emphasis added).

[42] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, CPI Inflation Calculator available at https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

[43] The minimum statutory royalty rate in effect during the 1992-93 period was 6.25¢. U.S. Copyright Office, Mechanical License Royalty Rates (Sept. 2018) available at https://www.copyright.gov/licensing/m200a.pdf.

[44] Respectfully, the Congress missed an opportunity to strike a blow for fairness in the Copyright Act of 1976 when it failed to index the 2¢ rate retroactively and instead treated a 70-year wage and price control as thought there were nothing to see here. Had Congress indexed the rate retroactively and then increased the rate prospectively based on value and indexed to inflation, songwriters would be exponentially better off. When songwriters complain to the CRB that they struggle to make a living, it is this decades long dark hole of the 2¢ rate freeze that is a major contributing factor and apparently punishment for some long-forgotten original sin. While the CRB is not tasked to fix all the songwriters’ financial woes, an argument could be made that it is at least partly responsible for fixing the ones cause by the government or at least not making it any worse by taking actions such as freezing mechanical royalty rates for twenty years.

You must be logged in to post a comment.