In George Orwell’s 1984, the “versificator” was a machine designed to produce poetry, songs, and sentimental verse synthetically, without human thought or feeling. Its purpose was not artistic expression but industrial-scale cultural production—filling the air with endless, disposable content to occupy attention and shape perception. Nearly a century later, the comparison to modern generative music systems such as Suno is difficult to ignore. While the technologies differ dramatically, the underlying question is strikingly similar: what happens when music is produced by machines at scale rather than by human experience?

Orwell’s versificator was built for scale, not meaning (reminding you of anyone?). It generated formulaic songs for the masses, optimized for emotional familiarity rather than originality. Suno, by contrast, uses sophisticated machine learning trained on vast corpora of human-created music to generate complete recordings on demand that would be the envy of Big Brother’s Music Department. Suno can reportedly generate millions of tracks per day, a level of output impossible in any human-centered musical economy. When music becomes infinitely reproducible, the limiting factor shifts from creation to distribution and attention—precisely the dynamic Orwell imagined.

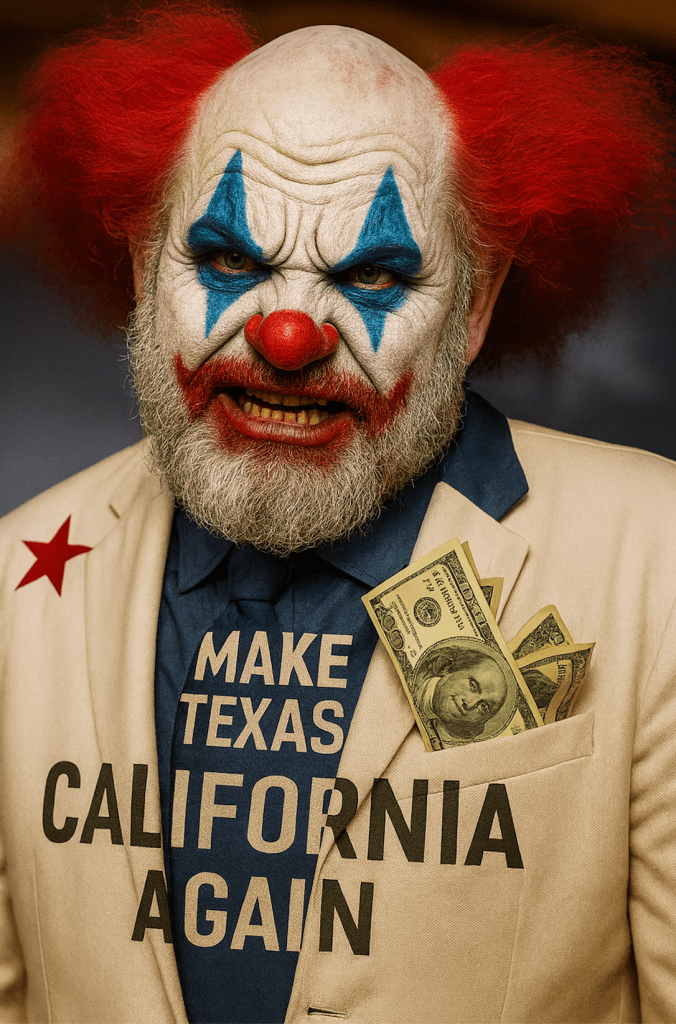

Nothing captures the versificator analogy more vividly than Suno’s own dystopian-style “first kiss” advertisingcampaign. In one widely circulated spot, the product is promoted through a stylized, synthetic emotional narrative that emphasizes instant, machine-generated musical cliche creation untethered from human musicians, vocalists, or composers. The message is not about artistic struggle, collaboration, or lived expression—it is about mediocre frictionless production. The ad unintentionally echoes Orwell’s warning: when culture can be manufactured instantly, expression becomes simulation. And on top of it, those ads are just downright creepy.

The versificator also blurred authorship. In 1984, no individual poet existed behind the machine’s output; creativity was subsumed into a system. Suno raises a comparable question. If a system trained on thousands or millions of human performances produces a new track, where does authorship reside? With the user who typed a prompt? With the engineers who built the model? With the countless musicians whose expressive choices shaped the training data? Or nowhere at all? This diffusion of authorship challenges long-standing cultural and legal assumptions about what it means to “create” music.

Another parallel lies in standardization. The versificator produced content that was emotionally predictable—pleasant, familiar, subservient and safe. Generative music systems often display a similar gravitational pull toward stylistic averages embedded in their training data that has been averaged into pablum. The result can be competent, even polished output that nevertheless lacks the unpredictability, risk, and individual voice associated with human artistry. Orwell’s concern was not that machine-generated culture would be bad, but that it would be flattened—replacing lived expression with algorithmic imitation. Substitutional, not substantial.

There is also a structural similarity in scale and economics. The versificator’s value to The Party lay in its ability to replace human labor in cultural production and to force the creation of projects that humans would find too creepy. Suno and similar systems raise analogous questions for modern musicians, particularly session players and composers whose work historically formed the backbone of recorded music. When a single system can generate instrumental tracks, arrangements, and stylistic variations instantly, the economic pressure on human contributors becomes obvious. Orwell imagined machines replacing poets; today the substitution pressure may fall first on instrumental performance, arrangement, sound designer, and production roles.

Yet the comparison has limits, and those limits matter. The versificator was a tool of centralized control in a dystopian state, designed to narrow human thought. Suno operates in a pluralistic technological environment where many artists themselves experiment with AI as a creative instrument. Unlike Orwell’s machine, generative music systems can be used collaboratively, interactively, and sometimes in ways that expand rather than suppress creative exploration. The technology is not inherently dystopian; its impact depends on how institutions, markets, and creators choose to shape it.

A deeper difference lies in intention. Orwell’s versificator was never meant to create art; it was meant to simulate it. Modern generative music systems are often framed as tools that can assist, augment, or inspire human creativity. Some artists use AI to prototype ideas, explore unfamiliar styles, or generate textures that would be difficult to produce otherwise. In these contexts, the machine functions less like a replacement and more like a new instrument—one whose cultural role is still evolving.

Still, Orwell’s versificator is highly relevant to understanding Suno’s corporate direction. When cultural production becomes industrialized, quantity can overwhelm meaning. The risk is not merely that machine-generated music exists, but that its scale reshapes attention, value, and recognition. If millions of synthetic tracks flood listening environments as is happening with some large DSPs, the signal of individual human expression may become harder to perceive—even if human creativity continues to exist beneath the surface.

The comparison between Suno and the versificator symbolizes the moment when technology challenges the boundaries of authorship, creativity, and cultural labor. Orwell warned of a world where machines produced endless culture without human voice. Today’s question is subtler: can society integrate generative systems in ways that preserve the distinctiveness of human expression rather than dissolving it into algorithmic slop?

The answer will not come from technology alone. It will depend on choices—legal, cultural, and economic—about how machine-generated music is labeled, valued, and integrated into the broader creative ecosystem. Orwell imagined a future where the machine replaced the poet. The task now is to ensure that, even in an age of generative AI, the humans remains audible.

You must be logged in to post a comment.