By Chris Castle

U.S. Representative Scott Fitzgerald joined in the MLC review currently underway and sent a letter to Register of Copyrights Shira Perlmutter on August 29 regarding operational and performance issues relating to the MLC. The letter was in the context of the five year review for “redesignation” of The MLC, Inc. as the mechanical licensing collective. (That may be confusing because of the choice of “The MLC” as the name of the operational entity that the government permits to run the mechanical licensing collective. The main difference is that The MLC, Inc. is an entity that is “designated” or appointed to operationalize the statutory body. The MLC, Inc. can be replaced. The mechanical licensing collective (lower case) is the statutory body created by Title I of the Music Modernization Act) and it lasts as long as the MMA is not repealed or modified. Unlikely, but we live in hope.)

I would say that songwriters probably don’t have anything more important to do today in their business beyond reading and understanding Rep. Fitzgerald’s excellent letter.

Rep. Fitzgerald’s letter is important because he proposes that the MLC, Inc. be given a conditional redesignation, not an outright redesignation. In a nutshell, that is because Rep. Fitzgerald raises many…let’s just say “issues”…that he would like to see fixed before committing to another five years for The MLC, Inc. As a member of the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet, Rep. Fitzgerald’s point of view on this subject must be given added gravitas.

In case you’re not following along at home, the Copyright Office is currently conducting an operational and performance review of The MLC, Inc. to determine if it is deserving of being given another five years to operate the mechanical licensing collective. (See Periodic Review of the Mechanical Licensing Collective and the Digital Licensee Coordinator (Docket 2024-1), available at https://www.copyright.gov/rulemaking/mma-designations/2024/.)

The redesignation process may not be quickly resolved. It is important to realize that the Copyright Office is not obligated to redesignate The MLC, Inc. by any particular deadline or at all. It is easy to understand that any redesignation might be contingent on The MLC, Inc. fixing certain…issues…because the redesignation rulemaking is itself an operational and performance review. It is also easy to understand that the Copyright Office might need to bring in some technical and operational assistance in order to diligence its statutory review obligations. This could take a while.

Let’s consider the broad strokes of Rep. Fitzgerald’s letter.

Budget Transparency

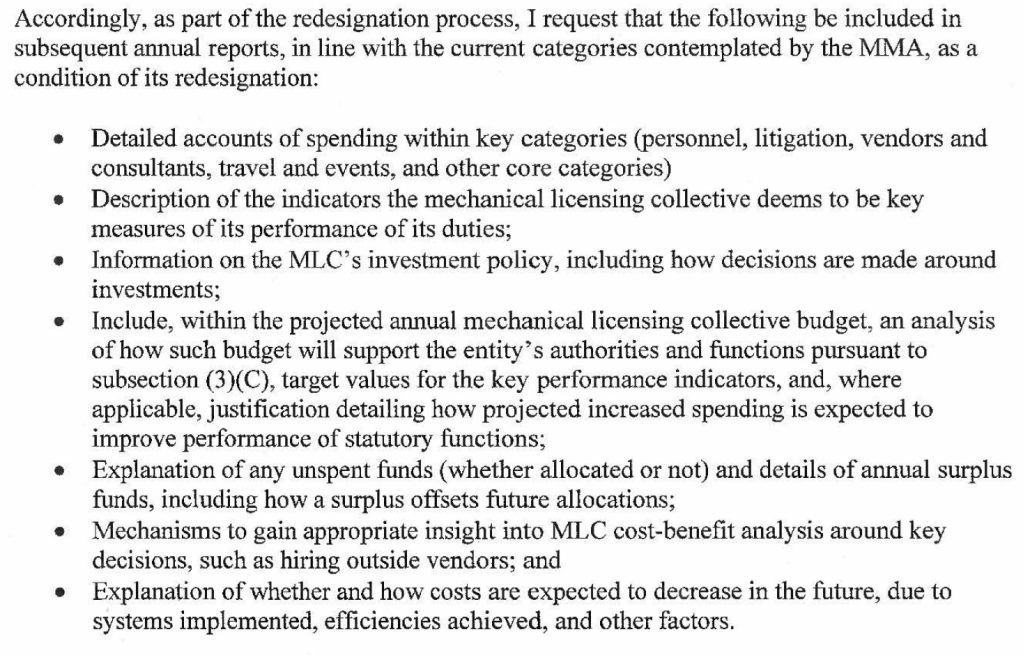

Rep. Fitzgerald is concerned with a lack of candor and transparency in The MLC, Inc.’s annual report among other things. If you’ve read the MLC’s annual reports, you may agree with me that the reports are long on cheerleading and short on financial facts. It’s like The MLC, Inc. thought they were answering the question “How can you tolerate your own awesomeness?” That question is not on the list. Rep. Fitzgerald says “Unfortunately, the current annual report lacks key data necessary to examine the MLC’s ability to execute these authorities and functions.” He then goes on to make recommendations for greater transparency in future annual reports.

I agree with Rep. Fitzgerald that these are all important points. I disagree with him slightly about the timing of this disclosure. These important disclosures need not be prospective–they could be both prospective and retroactive. I see no reason at all why The MLC, Inc. cannot be required to revise all of its four annual reports filed to date (https://www.themlc.com/governance) in line with this expanded criteria. I am just guessing, but the kind of detail that Rep. Fitzgerald is focused on are really just data that any business would accumulate or require in the normal course of prudently operating its business. That suggests to me that there is no additional work required in bringing The MLC, Inc. into compliance; it’s just a matter of disclosure.

There is nothing proprietary about that disclosure and there is no reason to keep secrets about how you handle other people’s money. It is important to recognize that The MLC, Inc. only handles other people’s money. It has no revenue because all of the money under its management comes from either royalties that belong to copyright owners or operating capital paid by the services that use the blanket license. It should not be overlooked that the services rely on the MLC and it has a duty to everyone to properly handle the funds. The MLC, Inc. also operates at the pleasure of the government, so it should not be heard to be too precious about information flow, particularly information related to its own operational performance. Those duties flow in many directions.

Board Neutrality

The board composition of the mechanical licensing collective (and therefore The MLC, Inc.) is set by Congress in Title I. It should come as no surprise to anyone that the major publishers and their lobbyists who created Title I wrote themselves a winning hand directly into the statute itself. (And FYI, there is gambling at Rick’s American Café, too.) As Rep. Fitzgerald says:

Of the 14 voting members, ten are comprised of music publishers and four are songwriters. Publishers were given a majority of seats in order to assist with the collective’s primary task of matching and distributing royalties. However, the MMA did not provide this allocation in order to convert the MLC into an extension of the music publishers.

I would argue with him about that, too, because I believe that’s exactly what the MMA was intended to do by those who drafted it who also dictated who controlled the pen. This is a rotten system and it was obviously on its way to putrefaction before the ink was dry.

For context, Section 8 of the Clayton Act, one of our principal antitrust laws, prohibits interlocking boards on competitor corporations. I’m not saying that The MLC, Inc. has a Section 8 problem–yet–but rather that interlocking boards is a disfavored arrangement by way of understanding Rep. Fitzgerald’s issue with The MLC, Inc.’s form of governance:

Per the MMA, the MLC is required to maintain an independent board of directors. However, what we’ve seen since establishing the collective is anything but independent. For example, in both 2023 and 2024, all ten publishers represented by the voting members on the MLC Board of Directors were also members of the NMPA’s board. This not only raises questions about the MLC’s ability to act as a “fair” administrator of the blanket license but, more importantly, raises concerns that the MLC is using its expenditures to advance arguments indistinguishable from those of the music publishers-including, at times, arguments contrary to the positions of songwriters and the digital streamers.

Said another way, Rep. Fitzgerald is concerned that The MLC, Inc. is acting very much like HFA did when it was owned by the NMPA. That would be HFA, the principal vendor of The MLC, Inc. (and that dividing line is blurry, too).

It is important to realize that the gravamen of Rep. Fitzgerald’s complaint (as I understand it) is not solely with the statute, it is with the decisions about how to interpret the statute taken by The MLC, Inc. and not so far countermanded by the Copyright Office in its oversight role. That’s the best news I’ve had all day. This conflict and competition issue is easily solved by voluntary action which could be taken immediately (with or without changing the board composition). In fact, given the sensitivity that large or dominant corporations have about such things, I’m kind of surprised that they walked right into that one. The devil may be in the details, but God is in the little things.

Investment Policy

Rep. Fitzgerald is also concerned about The MLC, Inc.’s “investment policy.” Readers will recall that I have been questioning both the provenance and wisdom of The MLC, Inc. unilaterally deciding that it can invest the hundreds of millions in the black box in the open market. I personally cannot find any authority for such a momentous action in the statute or any regulation. Rep. Fitzgerald also raises questions about the “investment policy”:

Further, questions remain regarding the MLC’s investment policy by which it may invest royalty and assessment funds. The MLC’s Investment Policy Statement provides little insight into how those funds are invested, their market risk, the revenue generated from those investments, and the percentage of revenue (minus fees) transferred to the copyright owner upon distribution of royalties. I would urge the Copyright Office to require more transparency into these investments as a condition of redesignation.

It should be obvious that The MLC, Inc.’s “investment policy” has taken on a renewed seriousness and can no longer be dodged.

Black Box

It should go without saying that fair distribution of unmatched funds starts with paying the right people. Not “connect to collect” or “play your part” or any other sloganeering. Tracking them down. Like orphan works, The MLC, Inc. needs to take active measures to find the people to whom they owe money, not wait for the people who don’t know they are owed to find out that they haven’t been paid.

Although there are some reasonable boundaries on a cost/benefit analysis of just how much to spend on tracking down people owed small sums, it is important to realize that the extraordinary benefits conferred on digital services by the Music Modernization Act, safe harbors and all, justifies higher expectations of those same services in finding the people they owe money. The MLC, Inc. is uniquely different than its counterparts in other countries for this reason.

I tried to raise the need for increased vigilance at the MLC during a Copyright Office roundtable on the MMA. I was startled that the then-head of DiMA (since moved on) had the brass to condescend to me as if he had ever paid a royalty or rendered a royalty statement. I was pointing out that the MLC was different than any other collecting society in the world because the licensees pay the operating costs and received significant legal benefits in return. Those legal benefits took away songwriters’ fundamental rights to protect their interests through enforcing justifiable infringement actions which is not true in other countries.

In countries where the operating cost of their collecting society is deducted from royalties, it is far more appropriate for that society to consider a more restrictive cost/benefit analysis when expending resources to track down the songwriters they owe. This is particularly true when no black box writer is granting nonmonetary consideration like a safe harbor whether they know it or not.

I got an earful from this person about how the services weren’t an open checkbook to track down people they owed money to (try that argument when failing to comply with Know Your Customer laws). Grocers know more about ham sandwiches than digital services know about copyright owners. The general tone was that I should be grateful to Big Daddy and be more careful how I spend my lunch money. And yes I do resent this paternalistic response which I’m sorry to say was not challenged by the Copyright Office lawyer presiding who shortly thereafter went to work for Spotify. Nobody ever asked for an open check. I just asked that they make a greater effort than the effort that got Spotify sued a number of times resulting in over $50 million in settlements, a generous accommodation in my view. If anyone should be grateful, it is the services who should be grateful, not the songwriters.

And yet here we are again in the same place. Except this time the services have a safe harbor against the entire world which I believe has value greater than the operating costs of the MLC. I’d be perfectly happy to go back to the way it was before the services got everything they wanted and then some in Title I of the MMA, but I bet I won’t get any takers on that idea.

Instead, I have to congratulate Rep. Fitzgerald for truly excellent work product in his letter and for framing the issue exactly as it should be posed. Failing to fix these major problems should result in no redesignation—fired for cause.

[This post first appeared in MusicTech.Solutions]

You must be logged in to post a comment.