Thank you @RepMariaSalazar, @RepDean, @RepNateMoran, @RepJoeMorelle, @RobWittman, & @RepAdamSchiff for introducing the NO FAKES Act in the House. It ensures their creative works are used with consent, credit, and compensation.

— Michael Huppe (@MikeHuppe) September 12, 2024

Support this legislation: https://t.co/TCIcejaKBT pic.twitter.com/2dE2M7Vc02

Fired for Cause: @RepFitzgerald Asks for Conditional Redesignation of the MLC

By Chris Castle

U.S. Representative Scott Fitzgerald joined in the MLC review currently underway and sent a letter to Register of Copyrights Shira Perlmutter on August 29 regarding operational and performance issues relating to the MLC. The letter was in the context of the five year review for “redesignation” of The MLC, Inc. as the mechanical licensing collective. (That may be confusing because of the choice of “The MLC” as the name of the operational entity that the government permits to run the mechanical licensing collective. The main difference is that The MLC, Inc. is an entity that is “designated” or appointed to operationalize the statutory body. The MLC, Inc. can be replaced. The mechanical licensing collective (lower case) is the statutory body created by Title I of the Music Modernization Act) and it lasts as long as the MMA is not repealed or modified. Unlikely, but we live in hope.)

I would say that songwriters probably don’t have anything more important to do today in their business beyond reading and understanding Rep. Fitzgerald’s excellent letter.

Rep. Fitzgerald’s letter is important because he proposes that the MLC, Inc. be given a conditional redesignation, not an outright redesignation. In a nutshell, that is because Rep. Fitzgerald raises many…let’s just say “issues”…that he would like to see fixed before committing to another five years for The MLC, Inc. As a member of the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet, Rep. Fitzgerald’s point of view on this subject must be given added gravitas.

In case you’re not following along at home, the Copyright Office is currently conducting an operational and performance review of The MLC, Inc. to determine if it is deserving of being given another five years to operate the mechanical licensing collective. (See Periodic Review of the Mechanical Licensing Collective and the Digital Licensee Coordinator (Docket 2024-1), available at https://www.copyright.gov/rulemaking/mma-designations/2024/.)

The redesignation process may not be quickly resolved. It is important to realize that the Copyright Office is not obligated to redesignate The MLC, Inc. by any particular deadline or at all. It is easy to understand that any redesignation might be contingent on The MLC, Inc. fixing certain…issues…because the redesignation rulemaking is itself an operational and performance review. It is also easy to understand that the Copyright Office might need to bring in some technical and operational assistance in order to diligence its statutory review obligations. This could take a while.

Let’s consider the broad strokes of Rep. Fitzgerald’s letter.

Budget Transparency

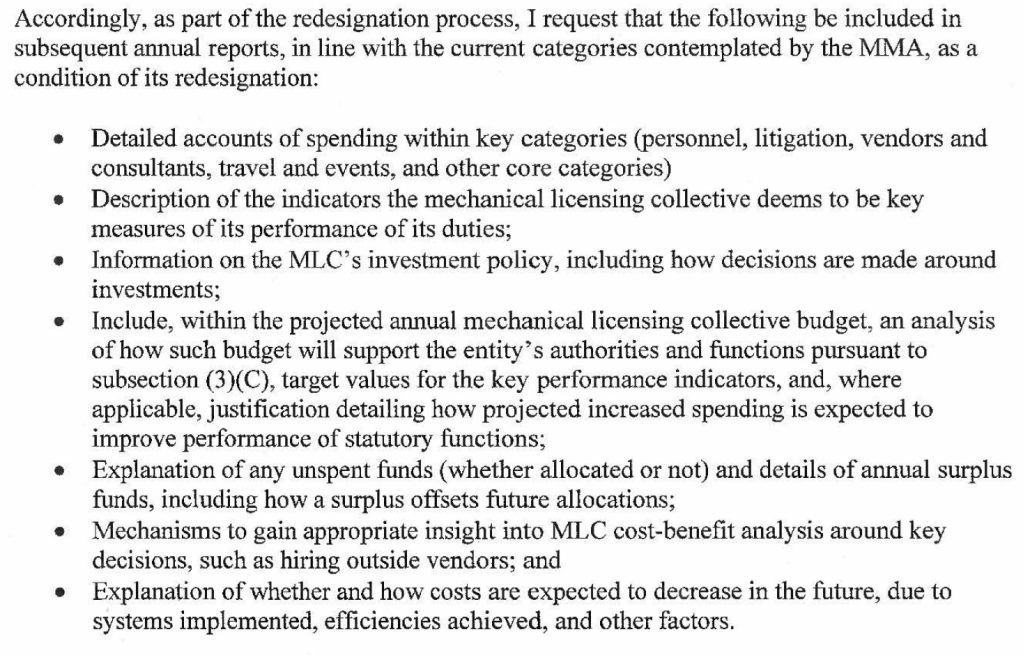

Rep. Fitzgerald is concerned with a lack of candor and transparency in The MLC, Inc.’s annual report among other things. If you’ve read the MLC’s annual reports, you may agree with me that the reports are long on cheerleading and short on financial facts. It’s like The MLC, Inc. thought they were answering the question “How can you tolerate your own awesomeness?” That question is not on the list. Rep. Fitzgerald says “Unfortunately, the current annual report lacks key data necessary to examine the MLC’s ability to execute these authorities and functions.” He then goes on to make recommendations for greater transparency in future annual reports.

I agree with Rep. Fitzgerald that these are all important points. I disagree with him slightly about the timing of this disclosure. These important disclosures need not be prospective–they could be both prospective and retroactive. I see no reason at all why The MLC, Inc. cannot be required to revise all of its four annual reports filed to date (https://www.themlc.com/governance) in line with this expanded criteria. I am just guessing, but the kind of detail that Rep. Fitzgerald is focused on are really just data that any business would accumulate or require in the normal course of prudently operating its business. That suggests to me that there is no additional work required in bringing The MLC, Inc. into compliance; it’s just a matter of disclosure.

There is nothing proprietary about that disclosure and there is no reason to keep secrets about how you handle other people’s money. It is important to recognize that The MLC, Inc. only handles other people’s money. It has no revenue because all of the money under its management comes from either royalties that belong to copyright owners or operating capital paid by the services that use the blanket license. It should not be overlooked that the services rely on the MLC and it has a duty to everyone to properly handle the funds. The MLC, Inc. also operates at the pleasure of the government, so it should not be heard to be too precious about information flow, particularly information related to its own operational performance. Those duties flow in many directions.

Board Neutrality

The board composition of the mechanical licensing collective (and therefore The MLC, Inc.) is set by Congress in Title I. It should come as no surprise to anyone that the major publishers and their lobbyists who created Title I wrote themselves a winning hand directly into the statute itself. (And FYI, there is gambling at Rick’s American Café, too.) As Rep. Fitzgerald says:

Of the 14 voting members, ten are comprised of music publishers and four are songwriters. Publishers were given a majority of seats in order to assist with the collective’s primary task of matching and distributing royalties. However, the MMA did not provide this allocation in order to convert the MLC into an extension of the music publishers.

I would argue with him about that, too, because I believe that’s exactly what the MMA was intended to do by those who drafted it who also dictated who controlled the pen. This is a rotten system and it was obviously on its way to putrefaction before the ink was dry.

For context, Section 8 of the Clayton Act, one of our principal antitrust laws, prohibits interlocking boards on competitor corporations. I’m not saying that The MLC, Inc. has a Section 8 problem–yet–but rather that interlocking boards is a disfavored arrangement by way of understanding Rep. Fitzgerald’s issue with The MLC, Inc.’s form of governance:

Per the MMA, the MLC is required to maintain an independent board of directors. However, what we’ve seen since establishing the collective is anything but independent. For example, in both 2023 and 2024, all ten publishers represented by the voting members on the MLC Board of Directors were also members of the NMPA’s board. This not only raises questions about the MLC’s ability to act as a “fair” administrator of the blanket license but, more importantly, raises concerns that the MLC is using its expenditures to advance arguments indistinguishable from those of the music publishers-including, at times, arguments contrary to the positions of songwriters and the digital streamers.

Said another way, Rep. Fitzgerald is concerned that The MLC, Inc. is acting very much like HFA did when it was owned by the NMPA. That would be HFA, the principal vendor of The MLC, Inc. (and that dividing line is blurry, too).

It is important to realize that the gravamen of Rep. Fitzgerald’s complaint (as I understand it) is not solely with the statute, it is with the decisions about how to interpret the statute taken by The MLC, Inc. and not so far countermanded by the Copyright Office in its oversight role. That’s the best news I’ve had all day. This conflict and competition issue is easily solved by voluntary action which could be taken immediately (with or without changing the board composition). In fact, given the sensitivity that large or dominant corporations have about such things, I’m kind of surprised that they walked right into that one. The devil may be in the details, but God is in the little things.

Investment Policy

Rep. Fitzgerald is also concerned about The MLC, Inc.’s “investment policy.” Readers will recall that I have been questioning both the provenance and wisdom of The MLC, Inc. unilaterally deciding that it can invest the hundreds of millions in the black box in the open market. I personally cannot find any authority for such a momentous action in the statute or any regulation. Rep. Fitzgerald also raises questions about the “investment policy”:

Further, questions remain regarding the MLC’s investment policy by which it may invest royalty and assessment funds. The MLC’s Investment Policy Statement provides little insight into how those funds are invested, their market risk, the revenue generated from those investments, and the percentage of revenue (minus fees) transferred to the copyright owner upon distribution of royalties. I would urge the Copyright Office to require more transparency into these investments as a condition of redesignation.

It should be obvious that The MLC, Inc.’s “investment policy” has taken on a renewed seriousness and can no longer be dodged.

Black Box

It should go without saying that fair distribution of unmatched funds starts with paying the right people. Not “connect to collect” or “play your part” or any other sloganeering. Tracking them down. Like orphan works, The MLC, Inc. needs to take active measures to find the people to whom they owe money, not wait for the people who don’t know they are owed to find out that they haven’t been paid.

Although there are some reasonable boundaries on a cost/benefit analysis of just how much to spend on tracking down people owed small sums, it is important to realize that the extraordinary benefits conferred on digital services by the Music Modernization Act, safe harbors and all, justifies higher expectations of those same services in finding the people they owe money. The MLC, Inc. is uniquely different than its counterparts in other countries for this reason.

I tried to raise the need for increased vigilance at the MLC during a Copyright Office roundtable on the MMA. I was startled that the then-head of DiMA (since moved on) had the brass to condescend to me as if he had ever paid a royalty or rendered a royalty statement. I was pointing out that the MLC was different than any other collecting society in the world because the licensees pay the operating costs and received significant legal benefits in return. Those legal benefits took away songwriters’ fundamental rights to protect their interests through enforcing justifiable infringement actions which is not true in other countries.

In countries where the operating cost of their collecting society is deducted from royalties, it is far more appropriate for that society to consider a more restrictive cost/benefit analysis when expending resources to track down the songwriters they owe. This is particularly true when no black box writer is granting nonmonetary consideration like a safe harbor whether they know it or not.

I got an earful from this person about how the services weren’t an open checkbook to track down people they owed money to (try that argument when failing to comply with Know Your Customer laws). Grocers know more about ham sandwiches than digital services know about copyright owners. The general tone was that I should be grateful to Big Daddy and be more careful how I spend my lunch money. And yes I do resent this paternalistic response which I’m sorry to say was not challenged by the Copyright Office lawyer presiding who shortly thereafter went to work for Spotify. Nobody ever asked for an open check. I just asked that they make a greater effort than the effort that got Spotify sued a number of times resulting in over $50 million in settlements, a generous accommodation in my view. If anyone should be grateful, it is the services who should be grateful, not the songwriters.

And yet here we are again in the same place. Except this time the services have a safe harbor against the entire world which I believe has value greater than the operating costs of the MLC. I’d be perfectly happy to go back to the way it was before the services got everything they wanted and then some in Title I of the MMA, but I bet I won’t get any takers on that idea.

Instead, I have to congratulate Rep. Fitzgerald for truly excellent work product in his letter and for framing the issue exactly as it should be posed. Failing to fix these major problems should result in no redesignation—fired for cause.

[This post first appeared in MusicTech.Solutions]

Press Release: Indie Songwriter Groups Thank @RepFitzgerald For His Letter to @CopyrightOffice Urging Improvements to the US Mechanical Licensing Collective

The Songwriters Guild of America (SGA), the Society of Composers & Lyricists (SCL) and the Music Creators North America (MCNA) coalition –on behalf of over ten thousand US songwriter and composer members and their heirs and with the support of tens of thousands more represented by our organizations’ affiliated International Council of Music Creators (CIAM)– offer our sincerest thanks and support to US Congressman Scott Fitzgerald (R-WI) for his stalwart efforts in seeking to protect our rights through much needed operational and structural improvements to the US Mechanical Licensing Collective (MLC). The MLC collects and distributes hundreds of millions of dollars in royalties to songwriters and composers through their music publishing administrators each year.

Following the filing by our coalition in May, 2024 of comments expressing conditional support for re-designation by the US Copyright Office of the current MLC if –and only if– certain reforms are instituted to improve its transparency, operational fairness and accuracy in distributions (https://www.songwritersguild.com/site/potential-re-designation-mlc-and-dlc) Representative Fitzgerald came forward with his own letter to the Copyright Office dated August 29, 2024 asserting the need for reforms in full basic harmony with our own positions. His Congressional office is one of many with whom our groups have had impactful and productive discussions concerning the need for closer governmental oversight of the MLC process in order to protect American music creator rights, as clearly intended by Congress in the Music Modernization Act enacted five years ago.

Among the urgently required reforms addressed in Congressman Fitzgerald’s letter are:

–greater MLC budgetary transparency,

–improved outreach and accuracy in identifying and contacting owners of unmatched “black box” royalties (potentially approaching one billion dollars in unmatched and/or undistributed funds by 2025), and

–improved MLC board neutrality, balance and fairness.

As to this latter issue, the Congressman was forthright in acknowledging that the MLC board has conducted itself more as an advocate solely for the corporate music publishing industry rather than, as Congressionally intended, an unbiased body charged principally with protecting creator’ rights and royalties.

There are several problems related to the presence on the MLC board of only four songwriter/composer directors as compared to ten music publisher representatives (a unique imbalance compared to all other music royalty collectives around the world), including the fact that “permanently” unmatched royalties are to be distributed by the MLC on a “market share”

basis.

That construct means that music publisher board members stand to benefit by NOT properly identifying and distributing royalties to their actual creator-owners, the very task legislatively assigned to the MLC at the time of its Congressional creation. Moreover, the alleged songwriter organizations’ representative appointed as the non-voting board overseer for music creator interests has proven to be nothing more than a rubber stamp for corporate interests in direct opposition to the creators’ interests it purports to safeguard. We are aware of no other American music creator group that supports continuation of this facade of creator “representation.”

Our groups appreciate the consistent outreach and earnest work of MLC chief executive officer

Kris Ahrend, but we join Congressman Fitzgerald and his supporting colleagues in the House and Senate in insisting that the enumerated reforms cited in our Copyright Office submissions must be considered essential prerequisites to MLC re-designation (including endorsement by the MLC Board of Congressional action to equalize board representation between music creators on the one hand and their corporate copyright owners and administrators on the other). Our coalition will meanwhile continue its work on Capitol Hill and with the Copyright Office advocating for genuine protections of independent, individual music creator rights by the MLC.

Read Rep. Fitzgerald’s letter here.

Press Release from @AmericanPublish: Appeals Court Affirms Decision Against Internet Archive for Copyright Infringement

[The defeat of Big Tech and the Internet Archive is one of the most important copyright cases in the last ten years. This press release is a good summary of the ruling from our allies at the Association of American Publishers.]

Today the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed the District Court’s March 2023 opinion in favor of publishers Hachette Book Group, HarperCollins, John Wiley & Sons, and Penguin Random House, finding Internet Archive liable for copyright infringement and rejecting all four factors of Internet Archive’s fair use argument.

The Court squarely addressed the question of whether it is “fair use” for a nonprofit organization to scan copyright-protected print books in their entirety, and distribute those digital copies online, in full, for free, subject to an asserted one-to-one owned-to-loaned ratio between its print copies and the digital copies it makes available at any given time, without any authorization from the copyright owner. In the Court’s words, “[a]pplying the relevant provisions of the Copyright Act, as well as binding Supreme Court and Second Circuit precedent, we conclude the answer is no.”

The following is a statement from Maria A. Pallante, President and CEO, Association of American Publishers:

“Today’s appellate decision upholds the rights of authors and publishers to license and be compensated for their books and other creative works and reminds us in no uncertain terms that infringement is both costly and antithetical to the public interest. Critically, the Court frontally rejects the defendant’s self-crafted theory of “controlled digital lending,” irrespective of whether the actor is commercial or noncommercial, noting that the ecosystem that makes books possible in fact depends on an enforceable Copyright Act. If there was any doubt, the Court makes clear that under fair use jurisprudence there is nothing transformative about converting entire works into new formats without permission or appropriating the value of derivative works that are a key part of the author’s copyright bundle.”

Key Quotes the Court’s decision:

- Within the framework of the Copyright Act, IA’s argument regarding the public interest is shortsighted. True, libraries and consumers may reap some short-term benefits from access to free digital books, but what are the long-term consequences?

- If authors and creators knew that their original works could be copied and disseminated for free, there would be little motivation to produce new works. And a dearth of creative activity would undoubtedly negatively impact the public. It is this reality that the Copyright Act seeks to avoid.

- Because IA’s Free Digital Library functions as a replacement for the originals, it is reasonable and logical to conclude not only that IA’s digital books currently function as a competing substitute for Publishers’ licensed editions of the Works, but also that, if IA’s practices were to become “unrestricted and widespread,” it would decimate Publishers’ markets for the Works in Suit across formats.

- Were we to approve IA’s use of the Works, there would be little reason for consumers or libraries to pay Publishers for content they could access for free on IA’s website. . .Thus, we conclude it is ‘self-evident’ that if IA’s use were to become widespread, it would adversely affect Publishers’ markets for the Works in Suit.

- IA does not perform the traditional functions of a library; it prepares derivatives of Publishers’ Works and delivers those derivatives to its users in full…Whether it delivers the copies on a one-to-one owned-to-loaned basis or not, IA’s recasting of the Works as digital books is not transformative.

- [B]ecause IA’s Free Digital Library primarily supplants the original Works without adding meaningfully new or different features that avoid unduly impinging on Publishers’ rights to prepare derivative works, its use of the Works is not transformative.

- Digitizing physical copies of written work is not transformative, because the act ‘merely transforms the material object embodying the intangible article that is the copyrighted original work.’

- The Copyright Act protects authors’ works in whatever format they are produced.

- IA’s Free Digital Library does not “improv[e] the efficiency of delivering content” without unreasonably encroaching on the rights of the copyright holder; it offers the same efficiencies as Publishers’ derivative works while greatly impinging on their exclusive right to prepare those works.

- While IA claims that prohibiting its practices would harm consumers and researchers, allowing its practices would―and does―harm authors.

The full decision can be found here.

Save the Date: 4th Annual Artist Rights Symposium on Nov. 20 in Washington DC

We’re excited to announce that the 4th Annual Artist Rights Symposium will be held on November 20, this time in Washington DC. We have some big surprises in store that will be announced soon with new partners and speaker lineups.

The topics we plan on covering will be ticketing, song metadata and black box issues, creator rights of publicity and transparency for artificial intelligence.

Watch this space!

@wordsbykristin: Legal Fights, Transparency & Neutrality: DiMA’s CEO On Improvements Streamers Suggest for the MLC

Kristin Robinson makes another important contribution to the artist rights conversation with her interview of Graham Davies, the new head of the Digital Media Association. Graham comes to DiMA from a background in the artist rights movement at our friends the Ivors Academy in the UK. We have high hopes for Graham who brings his intellect to clean up a long, long line of mediocrity at the DiMA leadership who are from Washington and here to help.

Kristin’s interview highlights DiMA’s recent filings in The Reup–the redesignation of the MLC by the Copyright Office that we’ve highlighted on Trichordist. He also has some well thought out analysis on how the MLC is not HFA, however similar the two may seem in practice.

This is an important interview and you can find it on Billboard (subscription required).

Here’s an example of Graham’s insight:

Do you think a re-designation every five years is not enough on its own?

I think it’ll be interesting to see what the re-designation process brings forward from the Copyright Office. Maybe the Copyright Office leans in on governance and says, “We’ve heard enough, and we can come forward with ideas.” But the re-designation process is a different thing than a governance review, which would bring in a special team to actually dig into governance-related issues and bring forward recommendations and proposals that could then be implemented. It would be something more specific and something the MLC could just do. You wouldn’t need the Copyright Office to sponsor it, though they could if they wanted to.

The Intention of Justice: In Which The MLC Loses its Way on a Copyright Adventure

by Chris Castle

ARTHUR

Let’s get back to justice…what is justice? What is the intention of justice? The intention of justice is to see that the guilty people are proven guilty and that the innocent are freed. Simple, isn’t it?

Only it’s not that simple.

From And Justice for All, screenplay written by Valerie Curtin and Barry Levinson

Something very important happened at the MLC on July 9: The Copyright Office overruled the MLC on the position the MLC (and, in fairness, the NMPA) took on who was entitled to post-termination mechanical royalties under the statutory blanket license. What’s important about the ruling is not just that the Copyright Office ruled that the MLC’s announced position was “incorrect”—it is that it corrected the MLC’s position that was in direct contravention of prior Copyright Office guidance. (If this is all news to you, you can get up to speed with this helpful post about the episode on the Copyright Office website or read John Barker’s excellent comment in the rulemaking.)

“Guidance” is a kind way to put it, because the Copyright Office has statutory oversight for the MLC. That means that on subjects yet to be well defined in a post-Loper world (the Supreme Court decision that reversed “Chevron deference”), I think it’s worth asking whether the Copyright Office is going to need to get more involved with the operations of the MLC. Alternatively, Congress may have to amend Title I of the Music Modernization Act to fill in the blanks. Either way, the Copyright Office’s termination ruling is yet another example of why I keep saying that the MLC is a quasi-governmental organization that is, in a way, neither fish nor fowl. It is both a private organization and a government agency somewhat like the Tennessee Valley Authority. Whatever it is ultimately ruled to be, it is not like the Harry Fox Agency which in my view has labored for decades under the misapprehension that its decisions carry the effect of law. Shocking, I know. But whether it’s the MLC or HFA, when they decide not to pay your money unless you sue them, it may as well be the law.

The MLC’s failure to follow the Copyright Office guidance is not a minor thing. This obstreperousness has led to significant overpayments to pre-termination copyright owners (who may not even realize they were getting screwed). This behavior by the MLC is what the British call “bolshy”, a wonderful word describing one who is uncooperative, recalcitrant, or truculent according to the Oxford Dictionary of Modern Slang. The word is a pejorative adjective derived from Bolshevik. “Bolshy” invokes lawlessness.

In a strange coincidence, the two most prominent public commenters supporting the MLC’s bolshy position on post-termination payments were the MLC itself and the NMPA, which holds a nonvoting board seat on the MLC’s board of directors. This stick-togetherness is very reminiscent of what it was like dealing with HFA when the NMPA owned it. It was hard to tell where one started and the other stopped just like it is now. (I have often said that a nonvoting board seat is very much like a “board observer” appointed by investors in a startup to essentially spy on the company’s board of directors. I question why the MLC even needs nonvoting board seats at all given the largely interlocking boards, aside from the obvious answer that the nonvoters have those seats because the lobbyists wrote themselves into Title I of the MMA—you know, the famous “spirit of the MMA”.)

Having said that, the height of bolshiness is captured in this quotation (89 FR 58586 (July 9, 2024)) from the Copyright Office ruling about public comments which the Office had requested (at 56588):

The only commenter to question the Office’s authority was NMPA, which offered various arguments for why the Office lacks authority to issue this [post-termination] rule. None are persuasive. [Ouch.]

NMPA first argued that the Office has no authority under section 702 of the Copyright Act or the MMA to promulgate rules that involve substantive questions of copyright law. This is clearly incorrect. [Double ouch.]The Office ‘‘has statutory authority to issue regulations necessary to administer the Copyright Act’’ and ‘‘to interpret the Copyright Act.’’ As the [Copyright Office notice of proposed rulemaking] detailed, ‘‘[t]he Office’s authority to interpret [the Copyright Act] in the context of statutory licenses in particular has long been recognized.’’

Well, no kidding.

What concerns me today is that wherever it originated, the net effect of the MLC’s clearly erroneous and misguided position on termination payments is like so many other “policies” of the MLC: The gloomy result always seems to be they don’t pay the right person or don’t pay anyone at all in a self-created dispute that so far has proven virtually impossible to undo without action by the Copyright Office (which has other and perhaps better things to do, frankly). The Copyright Office, publishers and songwriters then have to burn cycles correcting the mistake.

In the case of the termination issue, the MLC managed to do both: They either paid the wrong person or they held the money. That’s a pretty neat trick, a feat of financial gymnastics for which there should be an Olympic category. Or at least a flavor of self-licking ice cream.

The reason the net effect is of concern is that this adventure in copyright has led to a massive screwup in payments illustrating what we call the legal maxim of fubar fugazi snafu. And no one will be fired. In fact, we don’t even know which person is responsible for taking the position in the first place. Somebody did, somebody screwed up, and somebody should be held accountable.

Mr. Barker crystalized this issue in his comment on the Copyright Office termination rulemaking, which I call to your attention (emphasis added):

I do have a concern related to the current matter at hand, which translates to a long-term uneasiness which I believe is appropriate to bring up as part of these comments. That concern is, how did the MLC’s proposed policies [on statutory termination payments] come in to being in the first place?

The Copyright Office makes clear in its statements in the Proposed Rules publication that “…the MLC adopted a dispute policy concerning termination that does not follow the Office’s rulemaking guidance.”, and that the policy “…decline(d) to heed the Office’s warning…”. Given that the Office observed that “[t]he accurate distribution of royalties under the blanket license to copyright owners is a core objective of the MLC”, it is a bit alarming that the MLC’s proposed policies got published in the first place.

I am personally only able to come up with two reasons why this occurred. Either the MLC board did not fully understand the impact on termination owners and the future administration of those royalties, or the MLC board DID realize the importance, and were intentional with their guidelines, despite the Copyright Office’s warnings.

Both conclusions are disturbing, and I believe need to be addressed.

Mr. Barker is more gentlemanly about it than I am, and I freely admit that I have no doubt failed the MLC in courtesy. I do have a tendency to greet only my brothers, the gospel of Matthew notwithstanding. Yet it irks me to no end that no one has been held accountable for this debacle and the tremendous productivity cost (and loss) of having to fix it. Was the MLC’s failed quest to impose its will on society covered by the Administrative Assessment? If so, why? If not, who paid for it? And we should call the episode by its name—it is a debacle, albeit a highly illustrative one.

But we must address this issue soon and address it unambiguously. The tendency of bureaucracy is always to grow and the tendency of non-profit organizations is always to seek power as a metric in the absence of for-profit revenue. Often there are too many people in the organization who are involved in decision-making so that responsibility is too scattered.

When something goes wrong as it inevitably does, no one ever gets blamed, no one ever gets fired, and it’s very hard to hold any one person accountable because everything is too diffused. Instead of accepting that inevitable result and trying to narrow accountability down to one person so that an organization is manageable and functioning, the reflex response is often to throw more resources at the problem when more resources, aka money, is obviously not the solution. The MLC already has more money than they know what to do with thanks to the cornucopia of cash from the Administrative Assessment. That deep pocket has certainly not led to peace in the valley.

Someone needs to get their arms around this issue and introduce accountability into the process. That is either the Copyright Office acting in its oversight role, the blanket license users acting in their paymaster role through the DLC, or a future litigant who just gets so fed up with the whole thing that they start suing everyone in sight.

Saint Thomas Aquinas wrote in Summa Theologica that a just war requires a just cause, a rightful intention and the authority of the sovereign (Summa, Second Part of the Second Part, Question 40). So it is with litigation. We have a tendency to dismiss litigation as wasteful or unnecessary with a jerk of the knee, yet that is overbroad and actually wrong. In some cases the right of the people to sue to enforce their rights is productive, necessary, inevitable and—hopefully—in furtherance of a just cause like its historical antecedents in trial by combat.

It is also entirely in keeping with our Constitution. The just lawsuit allows the judiciary to right a wrong when other branches of government fail to act, or as James Madison wrote in Federalist 10, so the government by “…its several constituent parts may…be the means of keeping each other in their proper places.”

That’s a lesson the MLC, Inc. had to learn the hard way. Let’s not do that again, shall we not?

This post first appeared on the MusicTech.Solutions blog.

Are You Better Off Today Than You Were Five Years Ago? Selected comments on the MLC Redesignation: Songwriters Guild of America, the Society of Composers & Lyricists, and Music Creators North America Joint Comment

The Copyright Office solicited public comments about how things are going with the MLC to help the Office decide whether to permit The MLC, Inc. to continue to operate the Collective (see this post for more details on the “redesignation” requirement). We are impressed with the quality of many of the comments filed at the Copyright Office. While comments are now closed, you can read all the comments at this link.

For context, the “redesignation” is a process of review by the Copyright Office required every five years under the Music Modernization Act. Remember, the “mechanical licensing collective” is a statutory entity that requires someone to operate it. The MLC, Inc. is the current operator (which makes it confusing but there it is). If the Copyright Office finds the MLC, Inc. is not sufficiently fulfilling its role or is not up to the job of running the MLC, the head of the Copyright Office can “fire” the MLC, Inc. and find someone else to hopefully do a better job running the MLC. Given the millions upon millions that the music users have invested in the MLC, and the hundreds of millions of songwriter money held by the MLC in the black box, firing the MLC, Inc. will be a big deal. Given how many problems there are with the MLC, firing the MLC, Inc. that runs the collective

The next step in this important “redesignation” process is that The MLC, Inc. and the Digital Licensee Coordinator called “the DLC” (the MLC’s counterpart that represents the blanket license music users) will be making “reply comments” due on July 29. The Copyright Office will post these comments for the public shortly after the 29th. These reply comments will likely rebut previously filed public comments on the shortcomings of the MLC, Inc. or DLC (which were mostly directed at the MLC, Inc.) and expand upon comments each of the two orgs made in previous filings. If you’re interested in this drama, stay tuned, the Copyright Office will be posting them next week.

If you have been reading the comments we’ve posted on Trichordist (or if you have gone to the filings themselves which we recommend), you will see that there is a recurring theme with the comments. Many commenters say that they wish for The MLC, Inc. to be redesignated BUT…. They then list a number of items that they object to about the way the Collective has been managed by The MLC, Inc. usually accompanied by a request that the The MLC, Inc. change the way it operates.

That structure seems to be inconsistent with a blanket ask for redesignation. Rather, the commenters seem to be making an “if/then” proposal that if The MLC, Inc. improves its operations, including in some cases operating in an opposite manner to its current policies and practices, then The MLC, Inc. should be redesignated. Not wishing to speak for any commenter, let it just be said that this appears to be a conditional proposal for redesignation. Maybe that is not what the commenters were thinking, but it does appear to be what many of them are saying.

Today’s comment is jointly filed by the Songwriters Guild of America (SGA), the Society of Composers & Lyricists (SCL), and Music Creators North America (MCNA), who advocate for independent songwriters in contrast to the powers that be. (For clarity, the three groups in their comment refer to themselves together as the “Independent Music Creators”.)

For purposes of these posts, we may quote sections of comments out of sequence but in context. We recommend that you read their thoughtful and detailed joint comments in their entirety. You can read the joint comment at this link.

[The Current Crisis with Spotify]

Prior to proceeding to the presentation of our Comments, we are compelled by recent events and circumstances to issue the following, important caveat. Just days ago, the National Music Publishers Association (“NMPA”) announced its apparent intention to seek fundamental legislative changes to the US Copyright Act in regard to the statutory mechanical licensing system established under the Music Modernization Act (“MMA”) (the legislation that resulted in the creation of the MLC and the DLC). This complete reversal in NMPA policy is the result of repugnant actions on the part of the digital music distributor “Spotify” to minimize its royalty payment obligations by identifying and exploiting alleged loopholes in what many view as the unevenly negotiated and drafted Phonorecords IV settlement. The Independent Music Creators previously voiced formal opposition to the details of that settlement prior to its ratification and adoption by the US Copyright Royalty Board at NMPA’s urging in December, 2022.

This morass, which threatens to deprive music creators of hundreds of millions of dollars in royalties over the next five years, is made even more complex by the fact that both NMPA and the MLC are served by the same team of legal advisors. Those same legal advisors also counseled NMPA on the negotiation of the Phonorecords IV settlement, which the MLC (albeit through another set of litigators) is now seeking to enforce against Spotify in federal court (an action we support), and which NMPA is now essentially seeking to vacate through Congressional action to eliminate statutory mechanical licensing via an opt-out system (which predictably favors the major music publishing conglomerates over creators and small music publishers).

The general idea of eliminating statutory mechanical licensing, the revival of which movement may now unfortunately be viewed as a fig leaf to camouflage poor NMPA decision-making and execution regarding the Phonorecords IV settlement, is one that the Independent Music Creators and many members of the music publishing sector have long believed should receive serious consideration. We will support such legislative reforms if fairly framed and developed with meaningful independent music creator input, along with pursuing our own legislative proposals expressed below. For now, however, this entire situation could hardly be less transparent or conducive to quick resolution than it currently remains.

In short, neither the Independent Music Creators nor any other groups of interested parties can possibly develop complete and cogent opinions on the issue of re-designation of the MLC and DLC without having greater access to the full body of facts surrounding this crucial new development regarding Spotify. These Comments, therefore, must be viewed against the backdrop of an unresolved and economically crucial dispute, the fallout from and resolution of which may completely alter the views expressed herein in the immediate future. As such, we look forward to making further comments on this issue as additional facts are disclosed concerning the Spotify/MLC/NMPA relationships and conflicts (past and present).

MLC Board Composition: It bears further re-emphasis that most if not all of these suggested changes have been necessitated by the actions of the corporate-dominated MLC board, including the structure established by the MMA that allocates ten board seats to corporate music publishing entities (which in practice automatically grants control of the MLC board and of the entire organization to the three “major” publishers that together administer more than two-thirds of the world’s musical composition copyrights) compared with just four music creator board member seats. Under such circumstances, music creator board members are virtually powerless to effect influence over the board’s actions and MLC policy, and are relegated to serving merely as an amen chorus in support of every MLC-related music publisher action and demand. This system of publisher majority rule is contrary to the structures and rules of government-sanctioned royalty collectives everywhere else in the world. To our knowledge, no similar royalty and licensing collective in the world is controlled by a board with less than fifty percent music creator representation.

The sound of this figurative rubber stamp within the MLC boardroom is further amplified by the fact that since inception, the non-voting seat set aside for music creator organizational input has been occupied by a non-creator whose organization’s allegiance to following in lock step with the music publishing industry is so obvious as to be beyond rational dispute. Thus, the current reality is total, corporate music publisher influence and domination of MLC’s rules and policies. This, despite the fact that the MMA as codified in section 115 of the US Copyright Act specifically mandates that the music creator organizational seat be occupied by the representative of “a nationally recognized nonprofit trade association whose primary mission is advocacy on behalf of songwriters in the United States.” This situation must change.

You must be logged in to post a comment.