[This is crossposted from MusicTech.Solutions and is adapted from the author’s comment to the Copyright Office in the MLC regulations.]

By Chris Castle

If you’ve been following the evolution of the “aircraft carrier” revision of the U.S. Copyright Act styled the “Music Modernization Act,” you will remember that America now has a blanket license for the mechanical reproduction of songs (or will have as of 1/1/21). The “MMA” comes in three parts (or as I say three and one-half):

- Title I which establishes the blanket license, a willing-buyer willing-seller standard for mechanical royalty rate setting, the Mechanical Licensing Collective (called the “MLC”), the all-important safe harbor for Big Tech’s massive infringement of songs, and authorized the creation of the “musical works database” which is the subject of this post;

- Title I-1/2 which gives certain small benefits to ASCAP and BMI;

- Title II which provides meaningful relief and largely fixes the pre-72 loophole that the Turtles sued over (formerly the CLASSICS Act); and

- Title III which gives producers a statutory basis for SoundExchange royalties, another truly meaningful change.

I supported Title II and Title III, but I have lots of bones to pick with Title I, not the least of which has to do with the musical works database. A lot of my issues have to do with what I perceive as sloppy drafting and a mad rush to “get a bill” at all costs which has led to a strong need to “fix” a lot of “glitches” in Title I itself (such as the failure to dovetail the major change in the compulsory mechanical from a per-song basis to a blanket basis. This in turn has an affect on other copyright provisions such as the termination right for songwriters which is now having to get solved–maybe–through the caulking of regulations to cover sloppy workmanship. (Caulk cracks.)

For those of us who sweep up behind the elephants in the circus of life, I fear that the musical works database of other people’s things is an 11th Century solution to a 21st Century problem–a list of things that will be very difficult to get right and even more difficult to keep right, not unlike William the Conqueror’s Domesday Book. Static lists of dynamic things necessarily are out of date the moment they are fixed.

Who Owns the Crowdsourced Musical Works Database?

We are going to discuss Title I musical works database today from a very simple threshold question: Who owns it?

Spoiler alert: The public owns it. This is logical, but like so many things in the drafting of Title I, the drafting is glitchy, which is what you call it if you’re in a good mood. I apocryphally attribute the term “glitch” when applied to massive Internet data breaches to the Fathers of the Internet who did not take care that the cracks were sealed (looking at you, Vint Cerf).

When you consider that the most valuable asset of the MLC is going to be the song database, ownership matters. This database of other people’s things must be created by the efforts of potentially hundreds of thousands of songwriters given no choice in the matter. It would be a bit much for the U.S. Congress to require all this only to enrich one U.S. corporation controlled by the U.S. publishers by leveraging a compulsory license to create a very valuable private asset. Particularly a database paid for by still other people that might then get taken and given to a replacement MLC. (There’s that “taken” word again.) That’s typically not what Congress does.

Ownership matters to the Digital Licensee Coordinator, too. Let’s also remember that on paper, the MLC does not pay a penny for the cost of its operations, including the creation of the database. The entire cost of the MLC’s operations is borne by the users of the blanket license through an organization called the Digital Licensee Coordinator. (If you’re thinking what’s with these names, I know, I know. Forget it, Jake, it’s Washington.)

This database ownership issue has been raised to authorities a couple times, and no one has answered it. I made it part of a recent comment I filed with the Copyright Office in the current rule making for regulations implementing Title I. Maybe they’ll get around to answering the question this time. After a while, you have to wonder why they have not.

The MLC’s Short Track Record on Ownership of Other People’s Things

A side note demonstrating both that ownership matters and that The MLC is thinking about ownership: a service mark registration for “The MLC”. (A service mark is a kind of trademark.) There is a difference between “the MLC” and “The MLC”. That’s because “the MLC” is the organization envisioned by the Congress that has to be redesignated (think “re-approved”) by the Copyright Office every five years. On the other hand, “The MLC” refers to “The MLC, Inc.” which is the corporation created by the super popular proponents of Title I who were designated the first MLC and who style themselves “The MLC” using the definite article. But if I told you that there was a difference between “the MLC” and “The MLC” would you find that confusing?

The clear implication of the definite article seems to be that they don’t envision any future in which they will not be the MLC, i.e., will not be redesignated. They also probably don’t envision a future where a different corporation would be designated the MLC and The MLC would be looking for something to do. Maybe they know something we don’t, but there it is.

This also raises some interesting trademark questions should The MLC seek to prevent a successor from trading under the name “MLC”, interesting enough to stop The MLC from claiming a proprietary interest in the statutory description. That mark is arguably descriptive and probably should be denied. In fact it’s so descriptive it actually asserts a private intellectual property interest in the statutory language that describes the organization created by statute. Sort of like asserting a trademark in “TVA” or “ICC” or “FOIA”.

Should Songwriters Bust a Move to Create Value for The MLC?

Let’s be clear about who owns the Congressional database. As you will see, the musical works database does not belong to either the MLC or The MLC. If there is any confusion about that, the Copyright Office should clear it up right away (which would save having to go to other avenues to do the same thing). There really isn’t a practical alternative to the Copyright Office jurisdiction. Congress gave the Copyright Office broad regulatory powers over the MLC (and, therefore, The MLC).

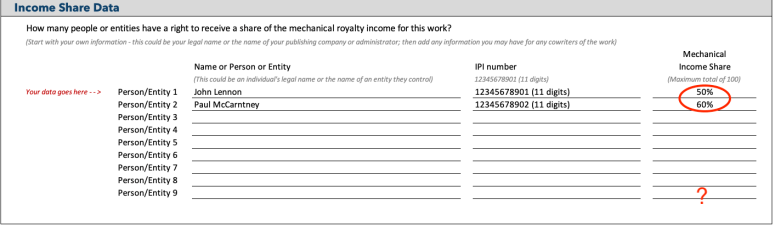

The public “musical works database” that Congress envisioned in Title I of the Music Modernization Act is largely a crowdsourced asset. Congress has asked the world’s songwriters or copyright owners to spend considerable time preparing their catalogs in whatever format The MLC and the DLC determine is good for The MLC (with the Office’s blessing through regulations). There inevitably will be quality control and accuracy review costs invested by the world’s songwriters and copyright owners in making sure that their catalogs are correctly reflected in the musical works database. “Copyright owners” may also include sound recording copyright owners asked to contribute their ISRCs or other data that they, too, have invested considerable expense in creating and maintaining.

Unfortunately, the transaction cost to the songwriter and copyright owner for participation in The MLC and crowdsourcing Congress’s database is an unfunded mandate at the moment. From a commercial perspective, the dynamic evolution of data is a potentially limitless expense, yet we have both this unfunded mandate which will spike in the early years but continue on a rolling basis essentially forever. Yet the MLC’s administrative assessment appears to be capped at a fixed increase by a settlement agreement. Again, a “glitch.” Still, The MLC’s executives seem positively giddy about their prospects with all the relief of someone who got tapped for lifetime employment with a pension (no doubt) while the songwriters these leaders are to serve are having the fight of their lives for survival.

What Did Congress Do? Or Not Do?

Yet, it seems clear that at the time of passing Title I, Congress had no intention of using a public law to create a private asset. Neither was their intention to use the law to leverage the creation of an asset for private ownership by whoever the head of the U.S. Copyright Office designated to be the MLC, regardless of how “popular” they might have been.

The creation of the musical works database is replete with hidden costs paid or incurred by songwriters and copyright owners. Neither the Congress nor the Copyright Royalty Judges were asked to directly address these hidden costs of creating the musical works database. (The Copyright Royalty Judges (or “CRJs”) are relevant because they approve the DLC’s financial contribution to the MLC through the “Administrative Assessment.” The assessment is intended to cover the “collective total costs” which includes broad categories of cost items related to the database.) And as usual, these costs appear to have gone straight over the heads of the Congressional Budget Office in their mandated assessment of the costs of Title I.

Even so, the MMA Conference Report from Congress addresses the cost issue head on:

The [Congress] rejects statements that copyright owners benefit from paying for the costs of collectives to administer compulsory licenses in lieu of a free market. Therefore, the legislation directs that licensees should bear the reasonable costs of establishing and operating the new mechanical licensing collective. This transfer of costs is not unlimited, however, since it is strongly cabined by the term ‘‘reasonable.’’[1]

It will be impossible for the “new mechanical licensing collective” to fulfill its statutory duties or build the complete musical works database to which the United States aspires without songwriters and copyright owners around the world doing the intensive and costly spade work to prepare their data to be exported to The MLC.[2] It is clear that the reasonable costs of preparing and exporting that data should be borne by The MLC[3] as part of the “Administrative Assessment.”[4] This material cost clearly is covered by the definition of “collective total costs”[5] and so was, or should have been, included in the current Administrative Assessment,[6] unless the intention was to cover The MLC’s side of these costs and force songwriters and copyright owners to eat their side of the same transaction. If that is the case, it would be helpful for the Copyright Office to clarify that intention in the name of transparency through their broad regulatory authority.

If there is another drafting glitch there, it is worth noting that the CRJs clearly contemplated revisiting the Administrative Assessment on their own motion for good cause.[7] If there were ever good cause, the staggering cost of registering potentially millions of songs would be it.[8]

It should be clear that no one’s intention was for the services to pay to create the musical works database and for the songwriters and copyright owners to labor to export their data to make the musical works database complete, only to have The MLC claim ownership of the musical works database, particularly if The MLC were not redesignated as the MLC following the five-year review by the Copyright Office. That unhappy “take my ball and go home” arbitrage event is foreseeable and would entirely cut against the “continuity” contemplated by Congress.[9]

It is critical that the Copyright Office clarify in regulations that neither The MLC nor any other MLC owns the musical works database. In fact, the MMA clearly states that “if a new entity is designated as the mechanical licensing collective, [the Office shall] adopt regulations to govern the transfer of licenses, funds, records, data, and administrative responsibilities from the existing mechanical licensing collective to the new entity.”[10] Since The MLC will have to transfer the musical works database and the other statutory materials to the new MLC if they fail to be redesignated, there should be no misconceptions that The MLC “owns” the database and could withhold all or part of it.[11] Because The MLC is just An MLC.

It should also be made clear that any MLC or DLC vendor does not obtain an ownership interest in any copy of all or part of the musical works database they may obtain for any reason.

Again, just like the termination right “glitch”, these are threshold questions that should have been answered in the statute itself.

Clarifying ownership of The MLC’s most important asset should be an easy ask of the Copyright Office. Watch this space to find out if it is.

* * * * * * * * *

[1] Report and Section-by-Section Analysis of H.R. 1551 by the Chairmen and Ranking Members of Senate and House Judiciary Committees, at 1 (2018) at 2 (emphasis added).

[2] This effort is referred to as “Play Your Part™” a business process trademarked by The MLC available at https://themlc.com/preparing-2021.

[3] I would point out that the way The MLC should work—and in the end probably will end up functioning as a practical matter–is that The MLC needs to be able to handle however songwriters ingest their data. Instead, it appears that The MLC is trying to dictate to all the songwriters in the world how they should assemble their song data beforethey register with The MLC. If The MLC wants to shift that burden, they should expect to pay for it. Otherwise, this is exactly backwards.

[4] 17 U.S.C. §115 (d)(7)(D). The Administrative Assessment is what makes the MLC different from other PROs or CMOs where members bear their own cost of participation. The Administrative Assessment is to cover the entire cost of creating the musical works database, not just The MLC’s startup or overhead costs. If nothing else, another way to treat these out of pocket costs is as a contribution to the operating costs of The MLC by songwriters and copyright owners that should be offset against future Administrative Assessments.

[5] 17 U.S.C. § 115 (e)(6).

[6] Order Granting Participants’ Joint Motion to Adopt Proposed Regulations, In re Determination and Allocation of Initial Administrative Assessment to Fund Mechanical Licensing Collective (U.S. Copyright Royalty Judges Docket No. 19-CRB-0009-AA (Dec. 12, 2019)).

[7] The CRJs included this footnote in their ruling on the administrative assessment (emphasis added): “The Judges have been advised by their staff that some members of the public sent emails to the Copyright Royalty Board seeking to comment on the proposed settlement agreement. Neither the Copyright Act, nor the regulations adopted thereunder, provide for submission or consideration of comments on a proposed settlement by non-participants in an administrative assessment proceeding. Consequently, as a matter of law, the Judges could not, and did not, consider these ex parte communications in deciding whether to approve the proposed settlement. Additionally, the Judges’ non-consideration of these ex parte communications does not: (i) imply any opinion by the Judges as to the substantive merits of any statements contained in such communications; or (ii) reflect any inability of the Judges to question, [on their own motion without a filing from a participant] whether good cause exists to adopt a settlement and to then utilize all express or reasonably implied statutory authority granted to them to make a determination as to the existence…of good cause [to reject the settlement now or in the future].” Order Granting Participants’ Joint Motion to Adopt Proposed Regulations, In re Determination and Allocation of Initial Administrative Assessment to Fund Mechanical Licensing Collective (U.S. Copyright Royalty Judges Docket No. 19-CRB-0009-AA (Dec. 12, 2019) n.1 (emphasis added)).

[8] There is a simple solution to determining these costs to songwriters and copyright owners. The Copyright Office could designate several metadata companies who could compete to handle the various steps of creating and exporting metadata to The MLC, such as in the CWR format, for example North Music Group and Crunch Digital have such tools. To avoid picking winners and losers and to preserve competition, the Office could alternatively establish a benchmark of quality control or some other criteria for becoming an approved company. The costs charged would likely vary depending on the size of the catalog, but The MLC need only pay the invoice of these companies which would be included in the Administrative Assessment. Obviously, the entity performing such work should be independent of The MLC, the DLC or any of its members, or any of their respective vendors. This would, of course, introduce the concept of competition into the monopoly which may interest no one but might benefit everyone.

[9] See H. Rep. 115-651 (115th Cong. 2nd Sess. April 25, 2018) at 6 (hereafter “House Report”); S. Rep. 115-339 (115thCong. 2ndSess. Sept. 17, 2018) at 5 (together with identical language, hereafter “legislative history”) (“Although there is no guarantee of a continued designation by the collective, the Committee believes that continuity in the collective would be beneficial to copyright owners so long as the entity previously chosen to be the collective has regularly demonstrated its efficient and fair administration of the collective in a manner that respects varying interests and concerns. In contrast, evidence of fraud, waste, or abuse, including the failure to follow the relevant regulations adopted by the Copyright Office, over the prior five years should raise serious concerns within the Copyright Office as to whether that same entity has the administrative capabilities necessary to perform the required functions of the collective.”)

[10] 17 U.S.C. § 115 (d)(3)(B)(ii)(A)(II).

[11] It seems that if an incumbent MLC that was not redesignated and continued to operate, it would almost unavoidably compete with the newly designated MLC but with a substantial leg up. I realize there have been some statements made about The MLC taking on work beyond the blanket license, such as voluntary licenses. That additional work might require additional investment, or a sharing of the total collective costs by third parties. I have not addressed that allocation as I for one would like to see The MLC stick to their knitting and succeed at the job they are obligated to do, and, frankly, paid to do, before worrying about expanding into profitable roles for the non-profit corporation. It does seem that if The MLC is not redesignated, there would not be much for them to do once they transfer the public’s assets to the new MLC.

But this week we got a look at what the elites have come up with in the form of the “Music Data Organization Form” that The MLC wants songwriters to use to “Play Your Part”. Remember–The MLC got the tens of millions of dollars from the services and they want you to “Play Your Part” and “Eat Your Costs” to play your part for free. Remember–they are the ones with a paycheck and fringe benefits paid for by the services that rip off songwriters every day.

But this week we got a look at what the elites have come up with in the form of the “Music Data Organization Form” that The MLC wants songwriters to use to “Play Your Part”. Remember–The MLC got the tens of millions of dollars from the services and they want you to “Play Your Part” and “Eat Your Costs” to play your part for free. Remember–they are the ones with a paycheck and fringe benefits paid for by the services that rip off songwriters every day.

You must be logged in to post a comment.