Here it is. The US economic data is undeniably leading to a stagflationary outlook reminiscent of the 1970s. If you don’t have first hand knowledge of the inflation that started under Nixon and Arthur Burns, burned through Ford and Carter and finally came to rest with Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volker and President Ronald Reagan that ultimately resolved in the low inflation that began trending downward in 1983, trust me; it was awful.

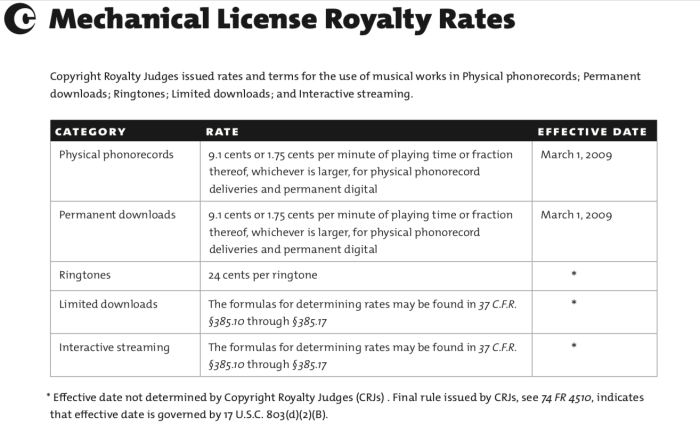

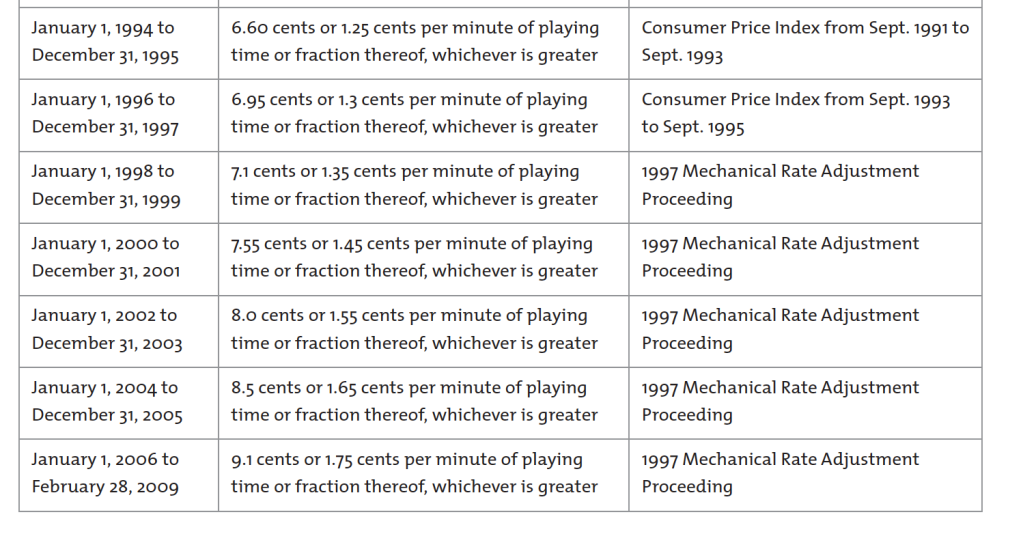

This is why it is insane–if not actually cruel–to force songwriters to take a fixed five year mechanical rate with no downside inflation protection in the form of a cost-of-living adjustment. What is bizarre is that this just happened in the streaming mechanical for the Phonorecords IV proceeding, in case you didn’t hear it over the sound of the backslapping.

It appears that songwriters will get the cost of living adjustment (or “COLA”) on the physical mechanical side–you know, the one the smart people told us was unimportant–but failed to get it on the streaming mechanical side which the smart people tell us is critical to the continuation of life as we know it. Even though it certainly looks more likely than not that growth of the money supply and government debt produces the rocket fuel for the inflation that took 1200 points off of the DJIA in one day. 1970s all over again, including James Taylor crooning “Fire and Rain.”

But economists are beginning to remind us that what makes anyone think the 1970s is the worst it can get? There’s a tendency to think of 1970s stagflation as a downside boundary. It’s not. It just happens to be the worst sustained economic times in living memory as the Depression-era Greatest Generation settles into the silence of old age. However, there’s nothing magical about the 1970s.

As it stands today, over 40 countries already have an inflation rate in the double digits, America is a debtor nation, Wall Street has sold a huge number of jobs off shore, productivity growth is lower than the 1970s and we’ve gone along with the central banks’ zero interest rate policies in the years since the 2008 crash. The piper must be paid for the Lehman Bros. of this world leading us all over the cliff in the great recession, even though the central banks’ easy money policy has delayed that payback. All of these are reasons why there must be a cost of living adjustment in any government imposed statutory rate that takes away bargaining rights. But wait, there’s more.

When Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell changed the Fed’s inflation targeting (remember “transitory inflation”?), he blew an opportunity to start fixing the real problem. But no more. The chickens are coming home to roost with increases in interest rates and yet-to-materialize promise of quantitative tightening. Now that Mr. Powell was reconfirmed for another term.

If there’s even a chance—any chance—that 1970s style stagflation and depression-level demand destruction may be the best we can hope for, anyone setting a wage control like the statutory mechanical royalty rate simply cannot order that rate for five years and fail to take into account the potential for a coming inflation spike even if the smart people sign a suicide pact. Yet this is exactly what just happened with the settlement of the streaming mechanical rates for Phonorecords IV at the Copyright Royalty Board.

Admittedly, the Copyright Royalty Judges are boxed in given the preference for voluntary settlements baked into the Copyright Act. That gives the smart people far too much credit and fails miserably to allow the Judges to do what judges do—bring contemplative thought to the problem. This is what judges do, it is not what lobbyists and their lawyers do. But unless the public raises the failure to include a cost of living adjustment in comments, so far there’s little basis for the Judges to correct the defective settlement.

It is essential that the Judges are allowed to do their job outside the hurley burley of the commercial relationship with the biggest corporations in history whose lawyers are hell-bent on conducting a scorched earth litigation campaign to crush songwriters. This is especially true of Google, Amazon and Spotify who have demonstrated truly vile behavior during the entire proceeding, a bully-fest beyond category.

George Johnson hit upon a potential solution in his recent comment. If one applies the COLA to the royalty pool after the mind-numbing “greater than/lesser of formula” created by those seeking full employment for lobbyists, lawyers and accountants, that’s actually a pretty elegant solution. I would quibble a little bit with the idea and apply the COLA as an uplift to the actual royalty statement so that the royalty recipients could see how that uplift was arrived at (which in theory would make them less likely to audit the MLC). That “show your work” approach would allow the payee to see how the MLC got there and make it easier to audit upstream for obvious mistakes.

It will also make it easier for the Judges to add the COLA because the building blocks of the calculation won’t change from the voluntary settlement (TCC, revenue share, etc.).

If songwriters are forced to stay in the confines of the statutory license trap, at least a COLA keeps the cheese from melting before their eyes. Plus they’re not required to guess today what the cost of food at home, shelter and gasoline will be five or six years from now.

The Judges would also have the opportunity to bring the services into a new era of fairness and wipe out the bullying of process as punishment that we all had to endure through two different proceedings.

Remember, as you have probably read or realized yourselves, all the US needs is one more good exogenous roundhouse shock to the economy (such as the world abandoning petrodollars for a basket of currency such as the ruble, the renminbi and the real to pick a few out of thin air), and we are in serious economic straights with hyperinflation as the real bugaboo.

Remember also that the US bonds pay interest at less than the inflation rate.

The decline of the dollar as the premier world reserve currency will put a stop to that interest/inflation spread practically overnight. The US government will not be able to borrow from a seemingly bottomless pit of lenders paying US dollars for US bonds at any price for the stability and transferability. What happens then? Probably interest rates will increase–a lot–to make it worth the lender’s money. Which means the debt service will take up an even bigger chunk of the US budget which will give us less to spend on the “Cross of Iron” weaponry that got us into the petrodollar business in the first place. And so it goes.

Songwriters may not be able to do anything tangible to stop cataclysmic economic events, but they can demand at least a bare minimum of downside protection through a COLA.

You may say, why so cynical? I’m not altogether cynical, I hope that I’m just cynical enough. The numbers don’t lie. If you know anyone who was a child during the Great Depression, or is the child of that person, ask them what it was like.

The overarching point is why would you want to take a chance and bet it all on the smart people?

The cheese or the trap. Which will you have?

You must be logged in to post a comment.