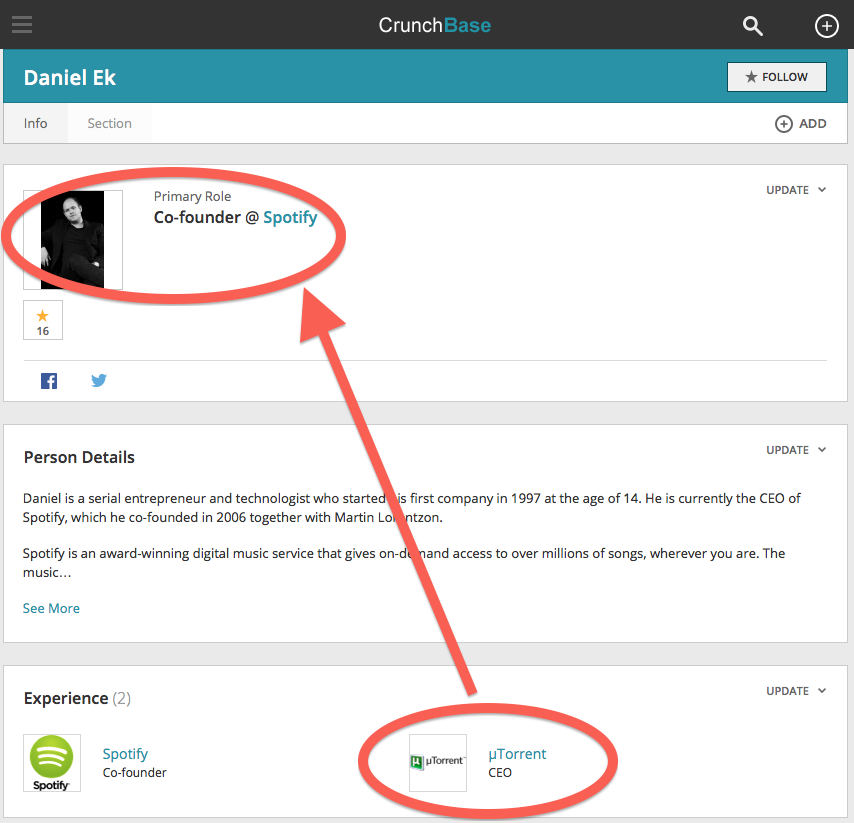

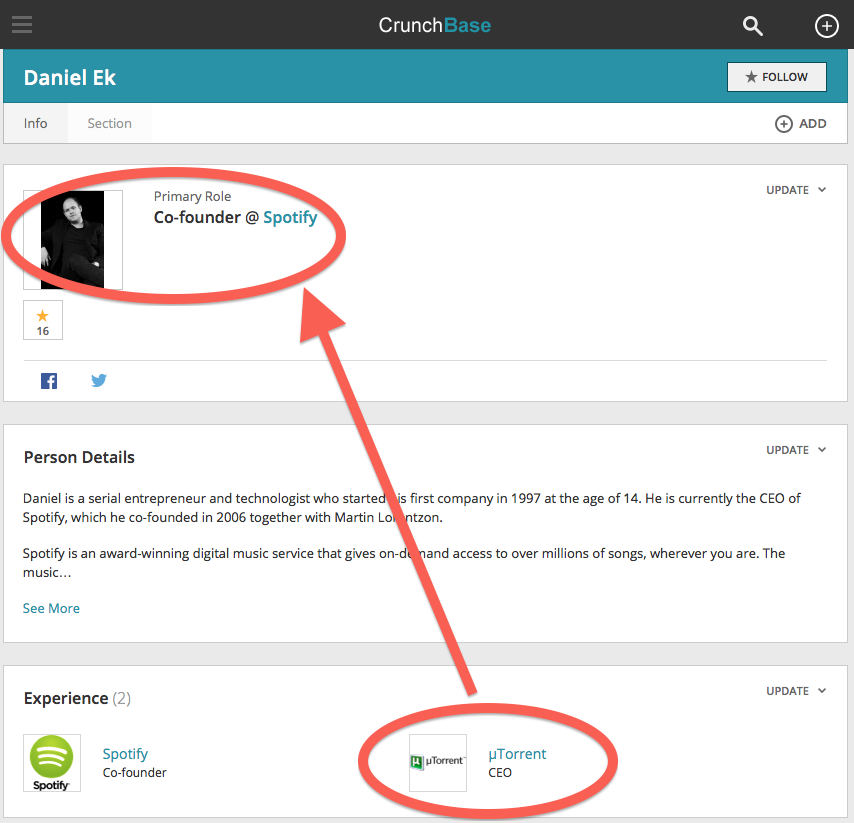

This is simply a story about intent. Daniel Ek is the co-founder of Spotify, he was also the CEO of u-torrent, the worlds most successful bit-torrent client. As far we know u-torrent has never secured music licenses or paid any royalties to any artists, ever.

Spotify could have completely avoided it’s legal issues around paying songwriters. The company could have sought to obtain the most recent information about the publishing and songwriters for every track at the service. The record labels providing the master recordings to Spotify are required to have this information. All Spotify (and others) had to do, was ask for it.

Here’s how it works.

For decades publishers and songwriters have been paid their share of record sales (known as “mechanicals”) by the record labels in the United States. This is a system whereby the labels collect the money from retailers and pay the publishers/songwriters their share. It has worked pretty well for decades and has not required a industry wide, central master database (public or private) to administer these licenses or make the appropriate payments.

This system has worked because each label is responsible for paying the publishers and songwriters attached to the master recordings the label is monetizing. The labels are responsible for making sure all of the publishers and writers are paid. If you are a writer or publisher and you haven’t been paid, you know where the money is – it is at the record label.

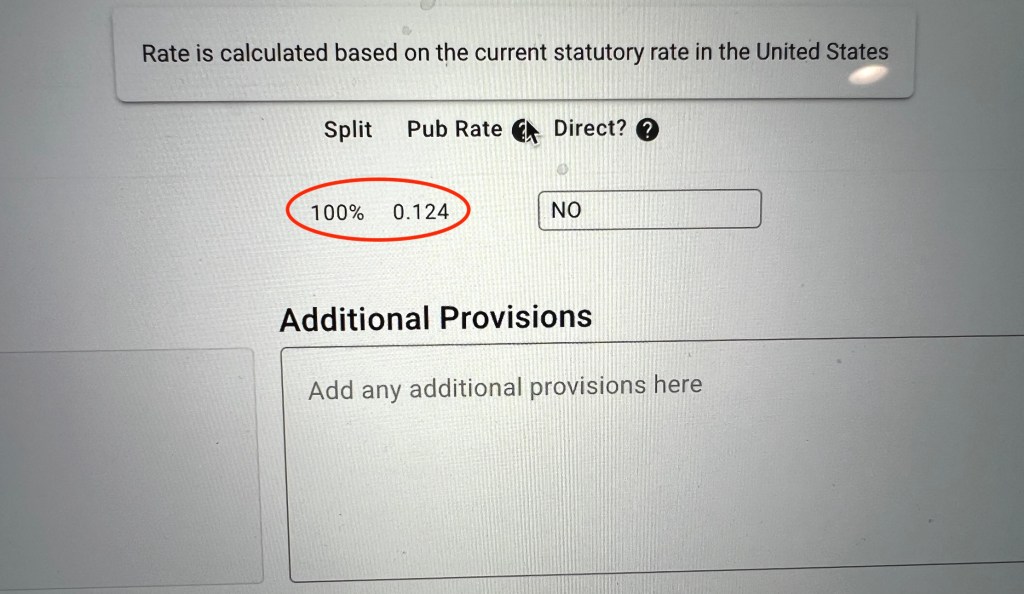

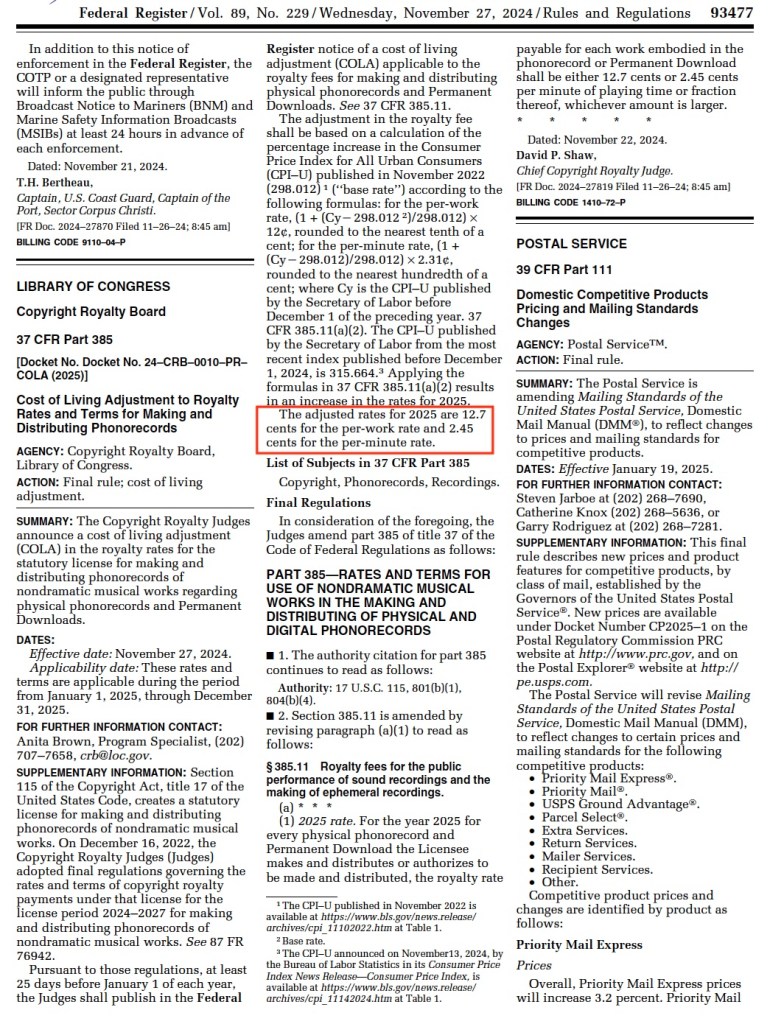

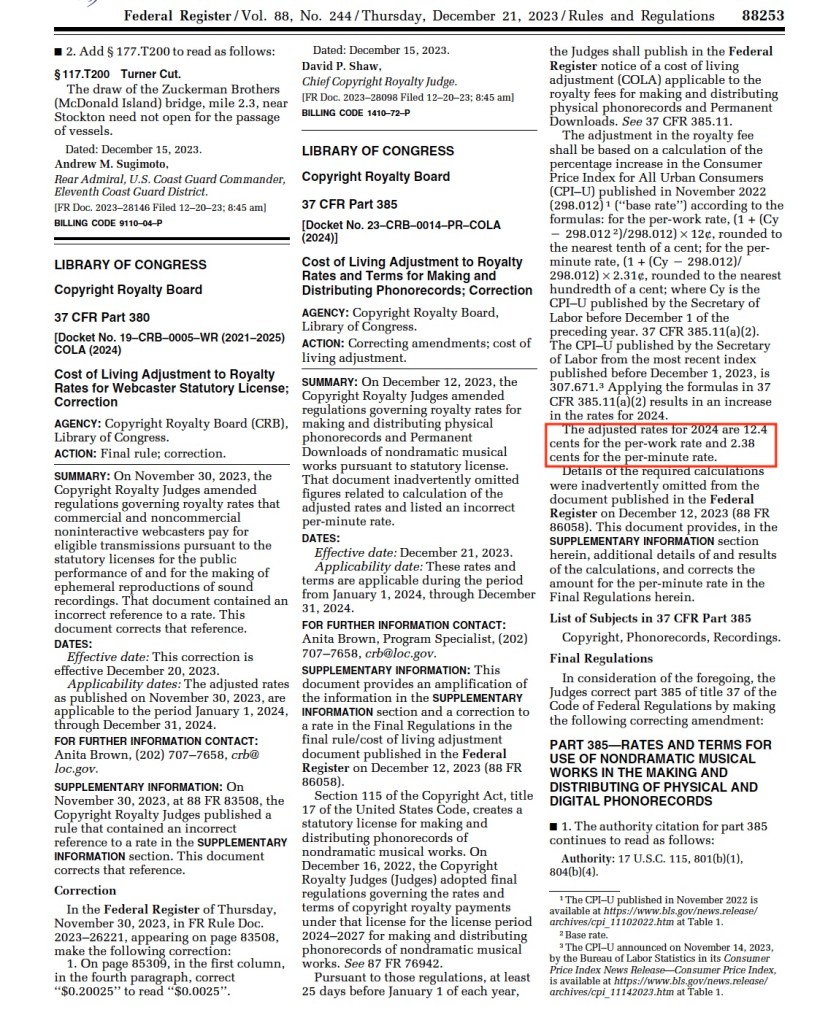

Streaming services pay the “mechanicals” at source which are determined by different formulas and rules based upon the use. For example non-interactive streaming and web radio (simulcasts and Pandora) are calculated and paid via the appropriate performing rights society like ASCAP or BMI. These publishing royalties are treated more like radio royalties.

The “mechanicals” for album sales from interactive streaming services are calculated in a different way. It is the responsibility of the streaming services to pay these royalties. CDBaby explains the system here and here. Don’t mind that these explanations are an attempt to sell musicians more CDBaby services, just focus on the information provided for a better understanding of this issue.

Every physical album and transactional download (itunes and the like) pays the “mechanical” publishing to the record label directly, who then pays the publishers and writers. This publishing information exists as labels providing the master recordings to Spotify have this information. All Spotify (and others) have to do, is ask for it.

Record labels have collectively and effectively “crowd sourced” licensing and payments to publishers and songwriters for decades. Why can’t Spotify simply require this information from labels, when the labels deliver their masters? It’s just that simple. Period.

The simple, easy, and transparent solution to Spotify’s licensing crisis is to require record labels to provide the mechanical license information on every song delivered to Spotify. The labels already have this information.

The simple solution is for Spotify to withdraw any and all songs from the service until the label who has delivered the master recording also delivers the corresponding publisher and writer information for proper licensing and payments. Problem solved!

No need for additional databases or imagined licensing problems. Every master recording on Spotify is delivered by a record label. Every record label is required by law to pay the publishers and songwriters. This is known and readily available information by the people who are delivering the recordings to Spotify!

There is no missing information, and no unknown licenses. Why is this so F’ing hard?

This system would mean that the record labels would have to provide this information. It’s also possible that some of that information is not accurate. Labels would probably fight against any mechanism that would make them have to make any claims about the accuracy of their data, which is fine. If it’s the most update information it’s a great place to start.

Of course, we know that both sides (both labels and streamers) will reject any mechanism that introduces friction into the delivery of masters. However, with the simple intent of requiring publisher and songwriter info for every song master delivered there will no longer be a problem at the scale that currently exists.

To be completely fair to Spotify they did work to make deals with the largest organizations representing publishers and songwriters (NMPA and HFA). However those two organizations leave out a lot of participants. So back to square one. If publishing information is required upon the delivery of masters, the problem is largely solved. Invoking a variation on Occam’s Razor, the best solution is usually the most simple one.

You’d think that in the times before computers this would have been harder than it is now, but like all things Spotify you have to question the motivations of a company whose founder created the most successful bittorrent client of all time, u-torrent.

Oh, and of this writing Spotify is now claiming they have no responsibility to pay any “mechanicals” at all. Can’t make this up.

You must be logged in to post a comment.