By Chris Castle

I am pleased to see that there is a consensus against more happy talk among commenters in The MLC, Inc.’s five year review of its operations at the Copyright Office. The consensus is an effort to actually fix the MLC’s data defects, rogue lawmaking and failure to pay “hundreds of millions of dollars” in black box royalties. But realize this is not just the songwriter groups you would expect to see raising objections (discussed in excellent Complete Music Update post). It’s also coming from some commenters who you would not expect to see criticizing The MLC who may not come right out and say it, but are essentially proposing a conditional redesignation.

When did Noah Build the Ark? The Two Arguments for Conditional Approval

There is a significant group, and sometimes from unexpected corners, who fall into two broad camps: One camp is “approve The MLC, Inc. with post-approval conditions” that may lead to being disapproved if not accomplished until the next five year review rolls around.

The other camp, which is the one I’m in if you’re interested, is to spend some time now getting very specific. The specifics are about crucial improvements The MLC, Inc. needs to put into effect and payments they need to make. This would be accomplished by bringing in advisory groups of publishing experts, especially from the independent community, roundtables, other customary tools for public consultations. But–the redesignation approval would occur only after The MLC, Inc. accomplished these goals.

Either way, the consensus is for conditions if not the timing. I’m not going to argue for one or the other today, but I have some thoughts about why delayed approval is more likely to accomplish the goals to make things better in the least disruptive way.

Remember, once The MLC, Inc. is approved, or “redsignated,” then all leverage to force change is lost. Why? Because if the last five years is any guide, exactly zero people will enforce the government’s oversight role and everyone knows it.

Putting operations-based obligations on The MLC, Inc. to be responsive to their members before they get the valuable approval preserves leverage and will force change one way or another, The reward for successfully accomplishing these goals is getting approved for another term (or the balance of their five year review). Noah built the Ark before the rain.

What if we fired them?

I’m actually pleased to see the consensus for conditional approval. Simply firing The MLC, Inc. would be disruptive (and they know it), mostly because the Copyright Office hasn’t gotten around to requiring that a succession plan be in place so that firing the MLC would not be disruptive. That’s a failure of oversight. You can’t expect the MLC to make it easy to fire themselves.

The simple solution to this pickle is for the Copyright Office to make any redesignation conditioned upon certain fixes being accomplished on an aggressive time frame. I say aggressive because they’ve had five years to think about this; it shoudln’t take long to at least implement some fixes. But if we don’t make it conditional the MLC will lack the incentive to actually fix the problems.

A conditional approval would simply say that if the MLC cleans up its act, say in the next 24 months, then they will be officially redesignated. If they don’t, it’s on to the next after that 24 month deadline.

Conditional Approval

I have to say I was encouraged by the number of commenters who said that The MLC, Inc. needs some very definite performance goals. Many commenters said that those goals needed to be met in order for The MLC, Inc. to get approved for another five years until the next review. I’m not quite sure how you approve them for another five years with performance goals unless you are really saying what some commenters came right out and said: Any approval should be conditional.

I think that means that the Copyright Office needs a plan with two broad elements: One, the plan identifies specific performance goals, and then two, establishes a performance timeline that The MLC, Inc. must meet in order for this current “redesignation” to become final.

That “conditional redesignation” would incentivize The MLC, Inc. to actually accomplish specific tasks like everyone else with a job. The timeline will likely vary based on the particular task concerned, but impliedly would be less than five years. There’s a very good reason to make the approval conditional; there’s just too much money involved. Other people’s money.

The Black Box

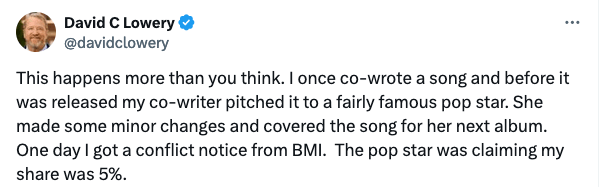

Every comment I read brings up the black box. Commenters raised different complaints about how The MLC, Inc. is managing or not managing the matching that is required for the black box distribution contemplated by Congress. They all were pretty freaked out about how big it is, how little we know about it, and the fact that the board of The MLC, Inc. is deeply conflicted because the lobbyists drafted an eventual market share distribution. Strangely enough, there’s every possibility that the market share distribution will happen, or could happen, right after the redesignation. Also known as losing on purpose in a fixed fight.

There’s an easy correction for that one–don’t do the market share distribution, maybe ever.

The harsh but near certain fact is if there is an announced market share distribution of the black box, the MLC (and everyone involved) will be sued before the actual distribution. It almost doesn’t matter how clean it is. So why do it at all? The MLC is supposed to set an example to the world, right? (And we know how much the world loves it when Americans say that kind of thing.) What if we said that the market share distribution was just bloodlust by the lobbyists salivating over a really big poker pot? On reflection, it should be put aside particularly because Congress may not have been told how big the black box really was if anyone knew at the time. Ahem….what did they know and when did they know it?

The Interest Penalty

This actually goes hand in hand with another interpretation of the black box provisions of Title I of the MMA which requires the payment of compound interest for black box money to be paid by The MLC, Inc. to the true copyright owner. That compound interest accrues at the “federal short term rate” in effect from time to time (that rate is adjusted monthly and is currently 5.01%). MLC’s interest obligation accrues in an account set up for the true copyright owner’s benefit, not for the recipients of the market share distribution.

Interest runs from the time the unmatched money is received by the MLC until it is matched and paid. There could easily be several different interest rates in effect if the unmatched royalties stay in the black box for months or particularly years. This concept is elaborated in a comment by the Artist Rights Institute. (And of course, why doesn’t the interest run from the time the black box is first held rather than the much later date that the unmatched is paid to the MLC?)

Title I requires this “penalty” the same way that it requires the statutory late fee which itself has been the subject of much negotiation. It is important to note that the word “penalty” does not appear in Section 115, but both the interest rate and the late fee are obviously “penalties” in plain English and in plain site. You don’t have to call it a thing a penalty in order for it to be a penalty. It doesn’t stop being a penalty just because the statute doesn’t define it as one, just like a large furry animal with big teeth, big claws, a loud roar and really bad breath who wants to eat you stops being a bear just because it doesn’t have a sign around its neck saying “BEAR”. Particularly when the furry animal has you by throat.

Align the Incentives

I have to imagine that a penalty of compound interest would incentivize both the MLC and the licensees who pay its bills to match that black box right quick. If a third party is paying the statutory interest penalty which is how it is now according to MLC CEO Kris Ahrend’s testimony to Congress (under oath), then there’s really no incentive for the MLC to pick up the pace on matching and there’s even less incentive for the licensees to make them do it.

It makes sense that the MLC is to maintain an account for each copyright owner (or maybe for each unmatched song since the copyright owner is not matched), so it only makes sense that these accounts and compound interest would be maintained on the ledger of the MLC rather than in a third party bank account, much less a mutual fund. It would be pretty dumb to just lump all the money into one account and run compound interest on the whole thing that would have to be disaggregated and paid out every time a song is matched. Assuming matching was the object of the exercise.

Plus, there’s nothing in Title I that says that black box money has to be put in a bank account that accrues interest so that the MLC doesn’t have to pay this penalty for being slow. Again, the word “bank” does not appear in Section 115. It definitely doesn’t say a federally insured bank account, a bank in the Federal Reserve system, or the like–because the statute does not require a bank. I would argue that if Congress meant for the money to be kept in a bank they would have said so.

Even so, I have to believe that if you want to an insurance company and said I will bring you the “hundreds of millions of dollars” if you write me a policy that will cover my interest expense and insure the corpus, somebody would take that business. If they can write derivatives contracts for fluctuations in natural gas futures in global energy markets, I bet they could write that policy or my name’s not Jeffrey Skilling.

William of Ockham Gets Into the Act

What makes a lot more sense and is a whole lot simpler is that Congress wanted to incentivize the MLC to match and pay black box royalties quickly. Congress established the compound interest penalty to add jet fuel to that call and response cycle following the jurisprudential theory of subsidiarity.

That penalty is part of the normal costs of operating the MLC therefore should be paid as part of the administrative assessment, i.e., by the services themselves. If the MLC sits on the money too long, the services can refuse to cover the interest costs beyond that point and the MLC can then pass the hat to the board members who allowed that to happen. Again, subsidiarity principles suggest that it is good government to create the incentive to fix a problem in the pocketbook of the one who is best positioned to actually get it fixed.

So everyone has a good incentive to clean out the black box. Brilliant lawmaking. I don’t think that’s such a bad deal for the services since they are the ones who sat on the money in the first place that produced the initial hundreds of millions of dollars for the black box. They got everything else they wanted in the MMA, why object to this little detail? Let’s try to hold down the hypocrisy, shall we?

There may be some arguments about that interpretation, but here’s what Congress definitely did not do and about which there should definitely not be an argument. Congress did not authorize the MLC to use the black box money as an investment portfolio. Nowhere in Title I is the MLC authorized to start an investment policy or to become a “control person” of mutual funds. Which they have done.

That investment policy also raises the question of who gets the upside and who bears the downside risk. If there’s a downturn, who makes the corpus whole? And, of course, when the ultimate market share distribution occurs, who gets the trading profits? Who gets the compound interest? Surely the smart people thought of this as part of their investment policy.

The Key Takeaway

You may disagree with the Institute’s analysis about what is and isn’t a penalty, and you may disagree about putting conditions on redesignation, but I think that there is broad agreement that there needs to be a discussion about forcing The MLC, Inc. to do a better job. I bet if you asked, the Congress clearly did not see the Copyright Office’s role as handing out participation trophies or pats on the head. And that should not be the community’s goal, either. This whole thing was cooked up by the lobbyists and they were not interested in any help. That obviously crashed and burned and now we need to help each other to save songwriters today and in future generations. If not us, then who; if not now, then when; if not here, then where?

[A version of this post first appeared on MusicTech.Solutions]

You must be logged in to post a comment.