Second Comments Submitted by the Songwriters Guild of America, Inc., the Society of Composers & Lyricists, Music Creators North America, and the individual music creators Rick Carnes and Ashley Irwin

These Comments Are Endorsed by the Following Music Creator Organizations:

Alliance for Women Film Composers (AWFC). https://theawfc.com

Alliance of Latin American Composers & Authors (AlcaMusica) https://www.alcamusica.org

Asia-Pacific Music Creators Alliance (APMA), https://musiccreatorsap.org/

European Composers and Songwriters Alliance (ECSA), https://composeralliance.org

The Ivors Academy (IVORS), https://ivorsacademy.com

Music Answers (M.A.), https://www.musicanswers.org

Pan-African Composers and Songwriters Alliance (PACSA), http://www.pacsa.org

Screen Composers Guild of Canada (SCGC), https://screencomposers.ca

Songwriters Association of Canada (SAC), http://www.songwriters.ca

Discussion

- The Statutory Importance of Interested, Non-Participant Comments to CRB Decision Making

While Congress may have expressed enthusiasm for joint rate setting proposals being developed through arms-length, independent negotiations among the parties to a CRB rate-setting proceeding (which clearly may not have been what transpired in the present case among vertically integrated parties),[1] Congress was also crystal clear in another of its related statutory directives. Namely, that the CRB also has a duty to ensure that interested, non-participating parties who would be bound by the terms of the negotiated agreement are given the full opportunity to comment upon the proposal as part of the record of the proceeding prior to the proposal’s adoption or rejection by the CRB.

Section 801(b)(7)(a)(i) of the US Copyright Act stipulates that:

[T]he Copyright Royalty Judges shall [1] provide to those that would be bound by the terms, rates, or other determination set by any agreement in a proceeding to determine royalty rates an opportunity to comment on the agreement and shall [2] provide to participants in the proceeding under § 803(b)(2) that would be bound by the terms, rates, or other determination set by the agreement an opportunity to comment on the agreement and object to its adoption as a basis for statutory terms and rates. (Bracketed numbers added for clarity)

More importantly for the purposes of these Comments, Section 801(b)(7)(a)(ii) explicitly sets forth the authority of the CRB to accept or reject the proposed agreements of parties to a proceeding based upon the combination of comments and objections filed both by participants in the proceeding and outside, interested party commenters:

[T]he Copyright Royalty Judges may decline to adopt the agreement as a basis for statutory terms and rates for participants that are not parties to the agreement, if any participant described in clause (i) objects to the agreement and the Copyright Royalty Judges conclude, based on the record before them if one exists, that the agreement does not provide a reasonable basis for setting statutory terms or rates. (emphasis added)

In the present case, the Major Music Conglomerates (once again counterintuitively joined by NSAI) have chosen to simply ignore the statutory requirements, set forth above, and focus solely on issuing a blanket rejection of the comments of pro se participant George Johnson (who formally objected to the proposed agreement). In fact, in their submission to the CRB of August 10, 2021,[2] the Major Music Conglomerates did not even bother to mention the detailed comments of those many individuals and groups who, on behalf of their constituents comprising a large percentage of the US’ and the world’s music creators, filed detailed comments with the CRB objecting to the proposed frozen mechanical rate deal as unreasonable.

Rather, the Conglomerates opted instead to stand solely on the following, naked assertion:

Mr. Johnson provides no basis for the Judges to reject the Settlement. Mr. Johnson makes unfounded accusations of fraud and inaccurate statements concerning the corporate structure of record companies, but provides no economic reason to believe that the rates in the Settlement are outside the “zone of reasonableness.” This is nothing more than a rehash of arguments he made and the Judges rejected when a similar settlement was presented in Phonorecords III….

Objections to a settlement that is substantially the same as the one adopted in Phonorecords III, absent a showing of changed market conditions that would support a change in the rates and terms for Subpart B configurations at this time, do not permit the Judges to “conclude that the agreement reached voluntarily between the Settling Parties does not provide a reasonable basis for setting statutory terms and rates.” (citation omitted). Thus, as in Phonorecords III, “the Judges must adopt the proposed regulations that codify the partial settlement.”[3] (emphasis added).

This evasive and misleading statement is counter-productive to upholding the Congressional mandate that all interested parties be heard –even those unable to afford the hundreds of thousands of dollars required to participate effectively in the formal rate-setting proceedings.

To repeat the obvious, when they filed the above comments, the Major Music Conglomerates were fully aware that Mr. Johnson was by far not the only person or entity to have filed detailed objections with the CRB to the frozen mechanical proposal, including the extensive comments of the Independent Music Creator groups who are the signatories hereto that had been submitted some two weeks prior to the filing of the Major Music Conglomerates’ comments on August 10, 2021 and reported on and published in the press.[4]

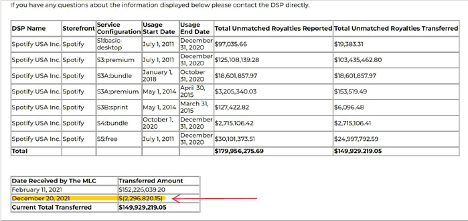

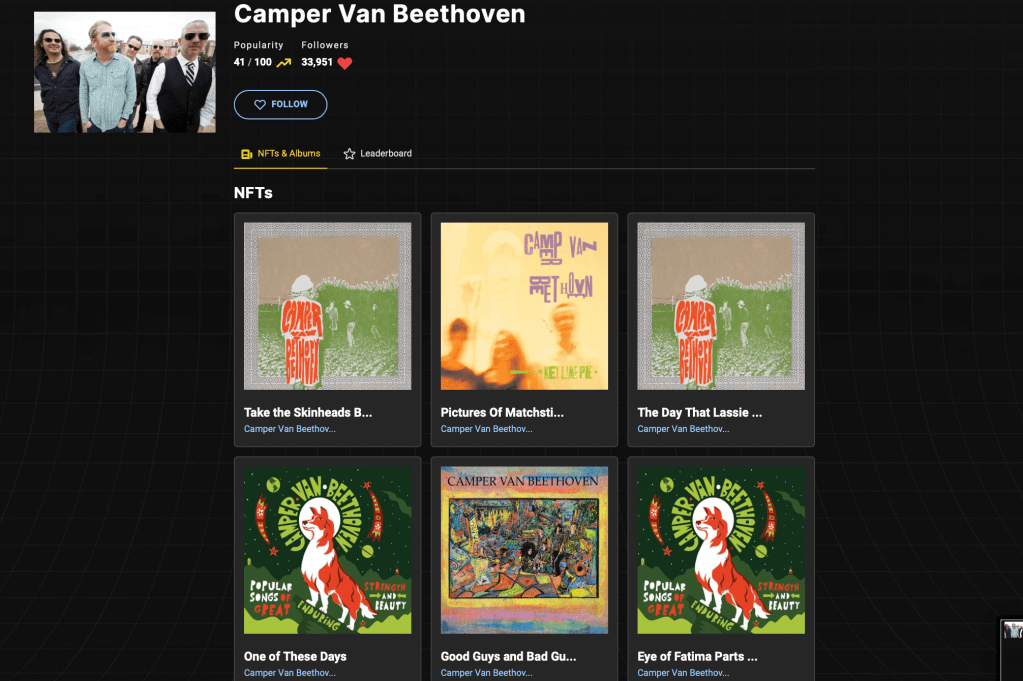

Specifically, some two dozen other organizations and individuals filed or endorsed comments[5] detailing with great specificity the unreasonable nature of the frozen royalty rate proposal made by the Major Music Conglomerates, owing to drastically changed market conditions that include the damage of long-term and now accelerating inflation, the growing length in time of the current freeze, and the demonstrably re-emerging physical phonorecord, download/Non-Fungible Token (NFT) markets amounting to tens of millions of dollars in annual royalty revenue for music creators. Those issues were spelled out extensively in our own Comments of July 26, 2021, and later updated in our Letter of October 20, 2021.

There is little mystery why the Major Music Conglomerates would choose not to acknowledge the existence of these many music creator dissenters, or to comment on what those dissenters had to say. As the CRB itself noted presciently in its Phonorecords III determination, “NMPA and NSAI represent individual songwriters and publishers.” For them to “engage in anti-competitive price-fixing at below-market rates,” would be against the interests of their potential constituents, who would likely “seek representation elsewhere” if they were so concerned.[6]

In the current instance, the Major Music Conglomerates seem to be actively seeking to obfuscate the fact that this result, for whatever reason, is exactly what has transpired. The multiple sets of comments received by the CRB from US and global music creator advocacy groups bluntly criticizing the frozen royalty rate proposal signify the raising of voices of those representing a vast portion of the world’s music creators against the proposal’s obvious inadvisability and irrationality. The isolated support for the proposal by NSAI, an organization that represents only a tiny sliver of US songwriters and composers principally from a single genre and local geographic area (and whose underwritten presence in the proceeding raises significant questions about whether it can truly represent any collection of songwriters and composers – let alone the actual, diverse universe whose rights and livelihoods are presently at stake), has been drowned out by hundreds of thousands of other music creators arguing substantively through their organizational representatives against the thoroughly unreasonable nature of extending frozen rates for another five-year period.

Thus is the specious nature of the Major Music Conglomerates’ central claim –that the CRB has neither the authority nor sufficient reason to reject the proposed mechanical rate freeze as unreasonable– demonstrated. Fulfilling all statutory requirements, a participant in the proceedings (George Johnson) has objected to the privately negotiated deal concocted by the vertically integrated Conglomerates. Further, numerous interested commentators who “would be bound by the terms, rates, or other determination set by the agreement” have joined with Johnson in providing to the CRB amply detailed comments demonstrating significant, multiple changes in circumstances that make the proposed agreement unreasonable and irrationally flawed in 2021.

Under such circumstances, the CRB would be well within the scope of its statutory authority to either “decline to adopt the agreement as a basis for statutory terms and rates for participants that are not parties to the agreement,” or to reject it altogether. We prefer the latter, but respectfully suggest that it should most certainly do one or the other.

Moreover, the assertion by the Major Music Conglomerates that the CRB lacks sufficient reason or authority to review the Memorandum of Understanding (“MOU”)[7] negotiated and agreed upon concurrently with the Frozen Rate Proposal for its effect on that rate proposal, is equally without merit. In their submission of August 10, 2021, the Conglomerates go so far as to claim that they “did not present the MOU to the Judges because they viewed it as routine, and irrelevant to the Judges’ decision-making concerning the Settlement.” To put it mildly, the Songwriter and Composer community views this statement with uneasiness as it pertains to the general issues of fairness and transparency in the Phonorecord IV proceeding, and hopes the CRB shares our concerns.

It suffices to say that two agreements –negotiated side by side with one another at the same time by the same parties regarding details of the same general matter—inarguably stand a substantial chance of being inter-related through both their content and potential quid pro quos. We therefore believe it obvious that in evaluating the fairness and reasonableness of one, the terms and scope of the other should be considered as a matter of course for reasons of both best practices and common sense.

[1] As stated in our Comments of July 26, 2021, it is by no means clear that the “negotiations” which took place among the vertically integrated participants in developing the frozen mechanical royalty rate proposal were at arm’s length. “The circumstances under which the settlement negotiations were conducted that produced the proposed royalty rate freeze set forth in the May 25 Motion to Adopt can be fairly characterized –under the above standards– as being exactly the opposite of what both Congress and the Executive Branch have in mind in defining “reasonability” under the “willing seller-willing buyer” formula. Rather than arm’s length negotiations between parties on opposites sides of the table, the referenced discussions that produced the settlement agreement instead seem to have taken place solely among vertically integrated parties and their trade association agents, apparently with little or no input from independent music creators and copyright owners[1] upon whom “those rates and terms [will be] binding.” See, Comments of July 26, 2021 at 8-9.

[2] https://app.crb.gov/document/download/25577

[3] https://app.crb.gov/document/download/25577 at 4-5.

[4] See, e.g., https://thetrichordist.com/2021/07/27/frozen-mechanicals-crisis-davidpoemusics-comment-to-the-copyright-royalty-board/ and https://thetrichordist.com/category/frozen-mechanicals/.

[5] See, https://app.crb.gov/case/detail/21-CRB-0001-PR%20%282023-2027%29 for comments filed between dates July 19 and August 2, 2021.

[6] Phonorecords III at 15298.

[7] According to the Major Music Conglomerates: “Specifically, this memorandum of understanding (“MOU”) provides for (1) participating record companies and music publishers to work collaboratively on licensing processes to improve clearance of new releases, (2) a procedure for bulk distribution of mechanical royalties accrued by participating record companies that are not otherwise payable, and (3) late fee waivers when participating record companies follow specified clearance procedures for new releases.” See, https://app.crb.gov/document/download/25577 at 6.

[Read the entire comment here]

You must be logged in to post a comment.