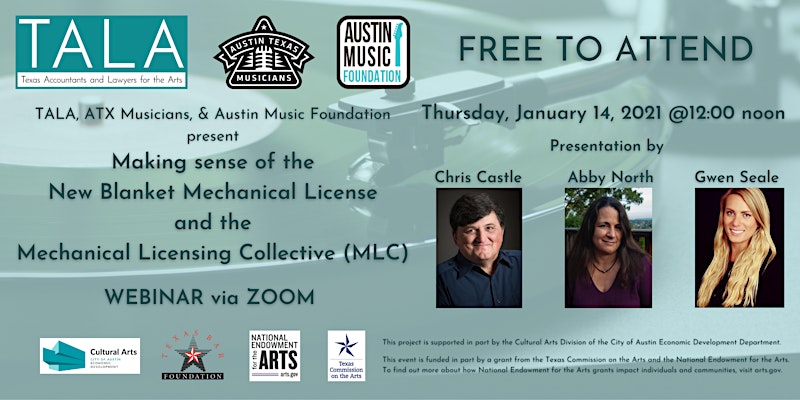

By Chris Castle

ARTHUR

Let’s get back to justice…what is justice? What is the intention of justice? The intention of justice is to see that the guilty people are proven guilty and that the innocent are freed. Simple isn’t it? Only it’s not that simple.

From …And Justice for All, written by Valerie Curtin and Barry Levinson.

Law out of balance is no law at all. I suggest that the DMCA is just this imbalance and the unbalanced DMCA has created other imbalances that in turn transferred wealth from the many to the few. One of the biggest dangers to our society currently and in the future is erosion of the third estate (or the “musician’s middle class”) into the concentration of wealth in fewer and fewer hands. This erosion is accompanied by its inevitable trend toward authoritarianism enforced by the mandarin class of Silicon Valley. Not to mention the policy laundering operations funded by transferred wealth like the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (that’s the Chan Zuckerberg who asked Xi Jinping to name her then-unborn child).

Serfing in the Apocalypse

This kind of neo-feudal concentration of wealth is most obvious in the tech oligarchy, especially in companies like Facebook, Google and Spotify with their dual class supervoting stock that concentrates the corporate decision making and wealth not in the shareholders but in the hands of Mark Zuckerberg, Sergey Brin, Larry Page, Eric Schmidt, Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzen. And then there’s Amazon with the world’s richest man, Jeff Bezos—the future space mogul. (Bezos’ Blue Origin and Google’s adventures in biometrics and AI in China are examples of the second order knock-on effects of the Internet oligarchy become defense contractors.)

I also suggest that one of the driving forces that has accelerated this concentration of wealth and power over the last twenty years has been the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act. Unless substantially reversed, the DMCA will continue to accelerate the wealth transfer from creators to oligarchs. It must also be said that state actors or near state actors like TikTok either profit from, promote or protect massive online piracy based in DMCA-type alibis. This topic is another conversation, but anyone who has dealt with the huge pirate sites has felt the cold hand of truly bad guys with top cover. In addition to the tech oligarchs, Russian oligarchs think the DMCA idea is really pretty groovy.

The DMCA Alibi

You’ve probably heard the expression “notice and takedown” applied to copyright online. It was the DMCA that created the “notice and takedown” alibi regime for piracy and near-piracy. These notices have come to be called “DMCA notices” and the Congressional plan that implemented that call and response has unambiguously failed. You may have also heard the expression “value gap.” The “value gap” is shorthand for illicit profits made from exploiting the DMCA loophole which itself is a prima facie case of law out of balance. The “value gap” is the predictable consequence of “notice and takedown.”

Google alone has received nearly five billion DMCA notices just in the current reporting period. That’s 5,000,000,000. I’m still waiting to see the conga line of Members of Congress and Senators who say that was exactly what they intended (and many who were involved in drafting the DMCA are still serving). I’m also waiting to hear lawmakers acknowledge that when something happens 5,000,000,000 times, it’s a feature not a bug just like the Ford Pinto’s exploding gas tank. No one ever asked them until Senator Thom Tillis began a series of hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Intellectual Property earlier this year.

If we’re lucky, in coming days Senator Tillis will be introducing a legislative overhaul of this gaping wound reflecting the many hearings he’s chaired this year to investigate the DMCA imbalance that created one of the biggest wealth transfers in history. That wealth transfer is not only caused by the perpetual state of piracy or near piracy created by the DMCA, it is also caused by the cost of enforcing copyright that has fallen on all creators in all copyright categories. Not to mention the sheer scale of the burden imposed by lawmakers on creators. Hopefully Senator Tillis’s investigation will bear fruit and will right the imbalance.

And as we have exhaustively endured for over 20 years, law out of balance is no law at all. In the music business, performers—like all creators—have been effectively powerless to stop this latest great imbalance in justice created by the copyright infringement safe harbor disaster and piracy force multiplier. That value gap has hollowed out the performer community (as well as record companies) after 20 years of wealth transfer to the Big Tech oligarchs from commoditizing the recordings that performers created. And Big Tech have used their DMCA-driven profits to hire even more lobbyists around the world to create even more loopholes in the human rights of artists in the endless maelstrom of Malthusian decline. That decline manifests itself in the ennui of learned helplessness of creators around the world as companies like Google seek to impose Google’s version of notice and takedown around the world.

Notice and Staydown

But—there is a new term in our lexicon that hopefully will appear in new legislation from Senator Thom Tillis: Notice and stay down. What does it mean? It’s a mid point between a pure negligence standard and the intent of the DMCA to provide a responsible alternative dispute resolution system. Instead of the endless whack a mole iterations of catch me if you can posting and reposting of infringing works, online service providers would be required to actually do the right thing and keep the infringing work off of their service. It’s really just a properly enforced repeat infringer policy. It’s hard to believe that adults persist in this whack a mole but they do. There’s big money in those moles that don’t actually stay whacked.

How in the world did we arrive at the status quo? A page of history is worth a volume of logic to fully understand this leading edge of the Great Reset.

The Great Copyright Reset

In the late 1990s, the large ISPs had a legitimate concern about this Internet thing. If ISPs (like Verizon or AT&T) are providing ways for the many to connect with each other over the Internet, they were inevitably empowering essentially anonymous users to send digitized property to each other by means of that same technology. That property might take the form of an email file attachment (or link to a file) that contained a copy of a sound recording, movie or an image. ISPs wanted to be protected from responsibility for things like copyright infringement they had nothing to do with. (This knowledge predicate is where the games begin.)

The ISPs needed a zone in which they could operate, a zone that came to be called the “safe harbor.” The deal essentially was that if you didn’t know or have a reason to know there was bad behavior going on with your users, or didn’t have knowledge waiving like a red flag, then the government would provide a little latitude to reasonable people acting reasonably.

This safe harbor idea was a great privilege conferred upon online service providers and balanced the democratizing nature of the Internet with the need to enforce the law against bad actors. Lawmakers were caught up with the idea of bringing people together. What they didn’t realize sufficiently was some of those people previously only met on Death Row.

Artists’ rights to protect themselves were not entirely extinguished by this new safe harbor for big companies but were severely burdened. Record labels and film studios had to devote substantial resources to whack a mole that could have been spent on their core businesses–making records and movies. If a copyright owner thought there was infringement going on that didn’t qualify for the safe harbor, then the intention was that individual artists shouldn’t have to file a lawsuit, they could just send a simple notice to the service provider. If it turned out that there was a bona fide dispute over the particular use of the work, then the parties could go to court and hash it out if necessary. The notice part of “notice and takedown” was perceived as an inexpensive remedy that would be available to artists who did not want to take on a lawsuit as well as ISPs with litigation budgets. The Congress did not factor in the charlatans who would come later like Google and Facebook, neither of which existed in 1998.

This is documented in the legislative history from 1998, i.e., both before Google and and Facebook and before the Electronic Frontier Foundation discovered Morpheus or Mrs. Lenz:

This ‘‘notice and takedown’’ procedure is a formalization and refinement of a cooperative process that has been employed to deal efficiently with network-based copyright infringement.

Section 512 does not require use of the notice and take-down procedure. A service provider wishing to benefit from the limitation on liability under subsection (c) must ‘‘take down’’ or disable access to infringing material residing on its system or network of which it has actual knowledge or that meets the ‘‘red flag’’ test, even if the copyright owner or its agent does not notify it of a claimed infringement.

Sounds very civilized, don’t it? Sounds like something that could be considered to be just. How could something that sounded so right go so wrong so fast? Notice and takedown has become notice and shakedown after the charlatans arrived.

The Inevitable Notice and Shakedown

The one thing that nobody thought was that it was the intention of Congress that there would be ad networks, multinational corporations and international piracy rings whose business model is in large part built on exploiting the “notice and takedown” loophole in that safe harbor.

These organizations ignored the DMCA’s knowledge predicate and repeat infringer requirements and adopted what is essentially a “catch me if you can” version that allows them to infringe until they get caught by the copyright owner and then continue to infringe if they are not sued–the exact opposite of what the DMCA intended. What once was a reasonable exception was almost immediately tainted as a massive loophole that the government has done little to nothing to correct much less enforce.

The “safe harbor” is no longer a loophole, it has graduated to a full blown design defect as indiscriminately harmful as any exploding gas tank. So now when artists ask that some common sense be applied to this grotesque distortion of the law-supposedly passed in part for the benefit of artists-some would tell artists that it’s not up to government to tell them what the law means. As Kafka-esque as that sounds.

Will You Believe Me or Your Lying Eyes?

Isn’t it obvious that having to send a notice for the same work on the same service hundreds of thousands of times an absurd burden? In other words — is the government actually defending whack a mole with a straight face? Did the government actually intend that 5,000,000,000 take down notices in a year are a new normal? If they did, evidence of that intent is not in the statute or the legislative history. Would Congress offer protection to an exploding gas tank after they already knew it was a threat because it was designed that way?

Whack a mole is not automatic-it requires human intervention. As we saw in BMG’s precedent setting and victorious lawsuit against the ISP Cox Communications over Cox’s grotesque failure to enforce its repeat infringer policy, a person has to decide to repost the infringing file even while knowing the file is or is very likely an infringement. Whack a mole actually defies the entire purpose of the safe harbor-whack a mole is not a little latitude for reasonable people acting reasonably.

Whack a mole is a design defect. Is it just that Congress should protect any design defect?

Let’s get back to justice. Not only does the status quo require creators to tell lawmakers (including courts) what their law means, the U.S. Government has utterly failed artists with the fundamental justification for the Sovereign common to our jurisprudence and political theory.

Crucially, it must be acknowledged that the government has failed to protect artists. The government has failed to enforce the laws, essentially overseeing and giving legitimacy to one of the largest wealth transfers of all time from the hands of the many into the overflowing pockets of the few. All based on an extreme interpretation by Google and its ilk of the government’s laws. Direct challenges to these interpretations involve costly and protracted litigation — with the inescapable whack a mole continuing all the while.

It would not be unreasonable for artists to think that the whole thing smacks of crony capitalism, particularly when one of the biggest beneficiaries of the loophole is a major lobbying influence like Google. While some ISPs have at least tried to address the issue, the Googles of this world are noticeably absent.

So I would beg pardon here-I do not feel that it should be necessary for artists to tell the Congress what would be acceptable in the way of parameters for “notice and stay down”, at least not initially. I think artists have the undisputed right to ask-actually to demand-of the Congress, what was their intention?

Enter the Foxes

Don’t underestimate the knock-on effects of the DMCA wealth transfer that funds self-preservation for the DMCA beneficiaries. Who can forget Google’s dominance of the Obama Administration? It’s clear that like Google learned from Microsoft, Facebook has learned from Google (and both joined forces to try to defeat the European Copyright Directive, so expect more of the same foxes coming for the henhouse when Senator Tillis introduces his bill).

We note the irony that the ethics czar for the Biden transition team is from Facebook, as is the director of legislative affairs a former Facebook lobbyist. A former Facebook board member co-chairs the transition team and there is a sprinkling of other former Facebook board members in other roles. Three transition team members are former Chan Zuckerberg Initiative employees. And Google’s Eric “Uncle Sugar” Schmidt will have a leading role.

Once they get into power, you can expect that DMCA reform will get exponentially harder, but the Tech Transparency Project will have even more work to do.

Senator Tillis Could Make Real Progress Toward Reversing the DMCA Cronyism

The safe harbor is the government’s law. They wrote it. They voted for it. They represented voters—including creators—when they did so. They presumably have some idea what it is supposed to mean. Many who voted for it are still in the Congress. The Congress needs to come clean on what they intended. Isn’t that the better place to start? Why should artists have to tell the Congress what the Congress’s intention was?

If it was the intention of the Congress (and President Clinton who signed the law) that the current state of whack a mole was the plan all along, then let them say that — and perhaps more importantly, point to where they told the electorate that was their intention at the time the DMCA was passed in the Congress and signed into law. If it is not their intention, then it should be reversed with no daylight.

Google alone is on track to receive over five billion take down notices this year alone. If this was the Congressional intention, then let them say that. If their intention was there should be no upper limit on the number of takedown notices any one company could receive in a year, then let them say that. And explain themselves.

And let’s be clear-Google does not appear to view these billions of notices as a design defect, although that would be a perfectly reasonable conclusion. And neither do Facebook or Twitter. One has to believe that if a company the size of Google viewed billions of notices as a problem, they could fix that problem. They haven’t. In fact the number of notices grows exponentially every year. Perhaps they view billions of DMCA notices as a feature set. Because along with the billions of notices comes a fortune for Google just like Facebook, Twitter and the rest. Big Tech’s defenders would say of Pirate Bay and Megavideo, they’re just like Google. Yes, that’s right. Google is just like them and they are just like Google. Serfing on the DMCA apocalypse.

What is the intention of justice? That the guilty are proven guilty. But if lawmakers won’t tell us what it means to be guilty much less prosecute the politically connected wrongdoers, then what justice is that?

Notice and stay down is a reasonable reaction to whack a mole, and one that is entirely consistent with the original intent of the DMCA notice and takedown regime that has gone so far wrong. Hopefully Senator Tillis will be leading the charge.

It might actually be that simple. Notice and stay down.

As Arthur told the jury, “If he’s allowed to go free, then something really wrong is going on here.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.